Why do our valued clients hear us talk about valuations so frequently? They have likely heard some variation of the below comments during investment strategy discussions over the past 6-12 months:

- It’s a great company and business model, but the valuation is simply too steep

- We’re concerned about overly optimistic earnings expectations for the US stock market

- This company’s growth trajectory is impressive, but we don’t think it’s an attractive investment

- There’s too much good news already in the price

Why the obsession with valuation? Don’t we ever just focus on buying the highest quality companies possible regardless of price? The short answer is no…never.

We do of course spend a great deal of time and effort identifying companies with strong competitive moats, clean balance sheets, able management, and a differentiated value-add for their customers alongside a long runway for growth. But we never make an investment decision on those factors alone because it’s only half of the picture. The other half is price, a fact that is often forgotten or neglected by much of the financial news media. In fairness to them, blathering on about earnings multiples is a lot less entertaining than highlighting exciting new businesses or nascent sectors. However, our job as portfolio managers isn’t to entertain, it’s to invest; it’s our belief that a great deal of the value added by an effective portfolio manager comes from maintaining a diligent focus on valuation, despite the slightly less stimulating nature of this part of the analysis. This is a concept we briefly explored in our most recent Capital Bulletin in the “Taking the Helm” section.

The two sentences below capture what we view as the yin and yang of the investment decision:

There is no price low enough to justify investing in a perpetually unprofitable stock

There is no stock so profitable that it can’t be ruined by an unreasonably high price

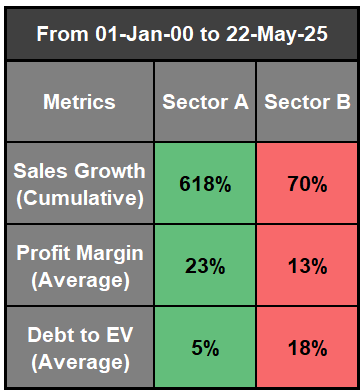

To illustrate this point, consider the following metrics from two unidentified sectors over the past 25 years.

From a business perspective, there can be no debate: Sector A is clearly superior in virtually every respect. Since the turn of the century, it has grown revenue faster than Sector B by a factor of nearly 10x, with higher profit margins and cleaner balance sheets on average. But does that translate into a better performing sector from an investment perspective? Let’s add on two additional rows to our table to find out.

Despite Sector B being inferior to Sector A across the board in terms of business metrics such as profitability, growth and debt, Sector B outperformed Sector A by an astonishing 4,652% over the 25-year holding period! How is this possible? The discrepancy can be explained with just one word: valuation.

The incredible growth and profitability of Sector A was not enough to overcome the enormous difference in valuation at the start of the period. The chart below shows the cumulative total return of the two sectors being compared (Sector A: Information Technology and Sector B: Tobacco).

This analysis should in no way be interpreted as an endorsement of the tobacco industry as an investment going forward or as a reflection on the moral qualities of either industry. However, it’s a particularly striking example of the immense power of valuation when it comes to performance. If a portfolio manager is focusing only on the business side, they are missing half of the picture. A diligent PM simply cannot make an informed investment decision about a stock without putting just as much weight on the valuation side.

The flip-side of this argument is that a singular focus on finding cheaply valued stocks can also lead to poor investment decisions (the dreaded “value trap”). We must of course look for good businesses that will grow revenue and profit over time. High multiple businesses often turn out to be great investments. But it’s our opinion that too often investors will look only at the yin of the business and neglect the yang of valuation.

Our ongoing cautiousness with respect to broad US equities is not necessarily because we think a recession is imminent (although the risk of one is much higher today than it was at year-end) or that earnings growth will be weak or negative. Our view is simply that there’s too much optimism priced in on the valuation side. The chart below shows that the average P/E of the S&P 500 is at a level that has only been exceeded three times since the turn of the century: 2000, 2002, and 2021. All three of these periods saw either negative or very weak 2-year forward returns.

This high valuation doesn’t mean US equities are guaranteed to perform poorly in the coming years, but it does mean that the average US stock has a very high bar to clear if it wants to justify these elevated valuations. Given a shift in US fiscal thrust and a great deal of lingering trade policy uncertainty, we believe the broad market will struggle to meet these expectations under the heavy burden of historically high valuations. This is also why we’ve been favouring international stocks so far in 2025 – when examining both sides of the picture, we think there are stronger opportunities at the margin in Europe and Asia than in the US, even if US earnings outpace international counterparts in the coming years.

While we wait to see if this thesis is borne out, rest assured that we will continue to maintain a diligent and holistic focus on both the business and valuation side of every investment decision.

Data Digest