Sails and Oars: Why Protecting the Ship is the Key to Progress

Imagine for a moment that you are the captain of a 19th century ship spending most of your life at sea without the benefit of modern meteorological technology. You’ve been given an opportunity to choose between one of two superpowers: to flawlessly predict every day of ideal weather, or to flawlessly predict every dangerous storm. Which would you choose? Clients who recall our recent discussion points or who have read our monthly newsletter over the last two quarters will know that our focus recently has been firmly on the latter – avoiding the storm and protecting on the downside. In the following three sections we’ll outline why we view avoidance of those storms as the key to long-term growth, and why stormy economic weather is the right time to bring in the sails and reach for the oars.

Storms and Sunshine – How the skew of market returns necessitates capital preservation over euphoric speculation.

Resist the Siren’s Call – How human psychology and market consolidation impair diversification and risk management.

Taking the Helm – How we select investments that display a higher margin of safety without sacrificing long-term growth.

Storms and Sunshine

We tabulated the daily, monthly and annual returns over the last 60 years for the US stock market, and the distribution of those returns would be described by a statistician as both leptokurtic and negatively skewed. For most of us this jargon carries little meaning, but if you answered “I’d rather be able to perfectly predict every dangerous storm” from the introductory question, you already intuitively understand this statistical distribution. Being able to perfectly forecast the best days to be on the water is much less beneficial than the ability to perfectly forecast the most dangerous days to be on the water. A day of clear skies means your progress for the day will be unhindered and enjoyable, but attempting to push through a storm can have potentially catastrophic consequences that extend far beyond a single day’s lost progress.

This is true of markets as well. The negative skew of market returns does not mean that stocks decline over time – we know the opposite is true. What it means is that the most extreme selloffs are more negative for long-term returns than the most extreme rallies are positive. This is evident in the fact that roughly 90% of all monthly US stock returns since 1965 were positive, but 90% of the most extreme monthly returns were negative.

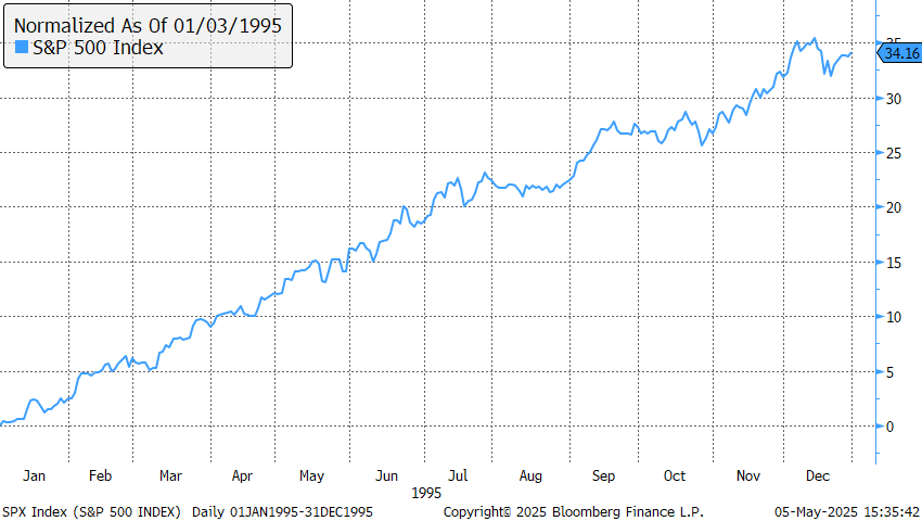

To illustrate this point, consider the best calendar year for US equities in the past 60 years (1995) relative to the worst calendar year in the past 60 years (2008). Good years for stocks tend to be marked by a steady climb higher where the economy is growing and investor optimism is improving sustainably. 1995 is a great example, as the S&P 500 advanced 34% that year in a gradual, steady climb. Rising productivity, strong economic growth, renewed investor optimism and an accommodative Federal Reserve provided the perfect environment for unhindered progress. Even in this spectacular year for investors, the monthly returns were remarkably steady at just ~2-4% per month.

Chart 1: Clear skies in 1995

Source: S&P, Bloomberg

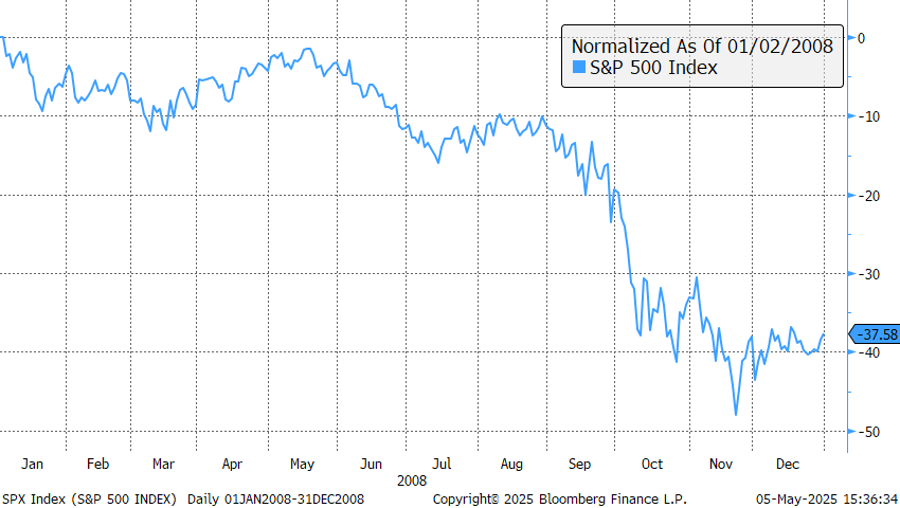

Now let’s look at the worst calendar year for stocks in recent history. The Global Financial Crisis pushed the market lower by 38% in 2008, but nearly half of this decline came in a single month (October).

Chart 2: The GFC storm was severe in October 2008

Source: S&P, Bloomberg

These two years on either end of the return spectrum are representative of how markets tend to behave: most periods are positive, but the selloffs pack a dangerous punch. This is why avoiding the most extreme negative periods has such a positive effect on long-term investment returns.

At this point the natural rebuttal would be to point out that it’s not possible to completely eliminate downside risk if one wants to enjoy the positive long-term returns provided by stock markets, and we certainly agree. However, there are things that can be done to limit the most severe impact on the downside, and we’ll lay out our thinking in more detail in Taking the Helm.

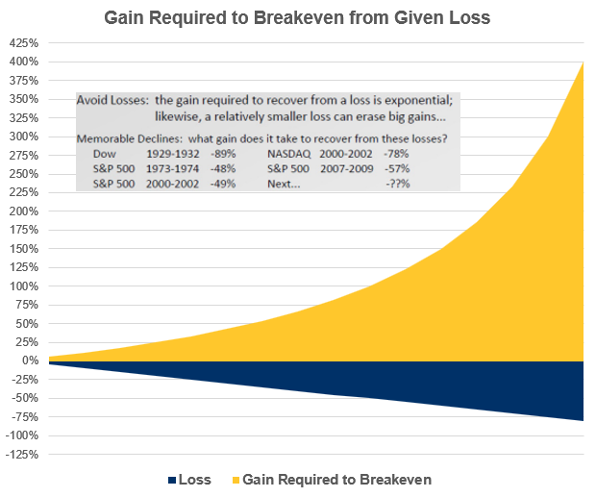

Before that, there’s another purely mathematical reason that mitigating market downside is so important: equal percentage declines on the upside and downside are not actually equivalent. Take the two years above as an example. Even though 1995’s positive percentage return (+34%) was nearly the same as 2008’s negative percentage return (-38%), an investor who hypothetically experienced these two years consecutively would be far from breaking even. If one invested $1,000,000 at the beginning of a two-year period which saw a +34% return followed by a -38% return (or vice versa), they would actually be down 17% in total, for a dollar loss of $170,200.

To put this in simpler terms, if you experience a 50% decline to $500k, you will be far from breaking even if you then earn +50% on that $500k. You would need to double your $500k (100% return) just to recover from the 50% loss. The point of all this is to point out that equivalent percentage declines and increases do not create for a round-trip, as shown below.

Chart 3: Those who bought the Nasdaq in the dotcom bubble needed a ~400% gain to break even

Source: RBC DS, Crestmont Research

One of our investing principles is to add risk when markets are irrationally fearful and reduce risk when markets are irrationally exuberant, but the factors laid out in this section explain why we tend to put particular focus on protecting against the most extreme downside in all time periods. Put simply, there is more to gain from avoiding the most extreme selloffs than there is to gain from fully capturing the most extreme rallies.

Resist the Siren’s Call

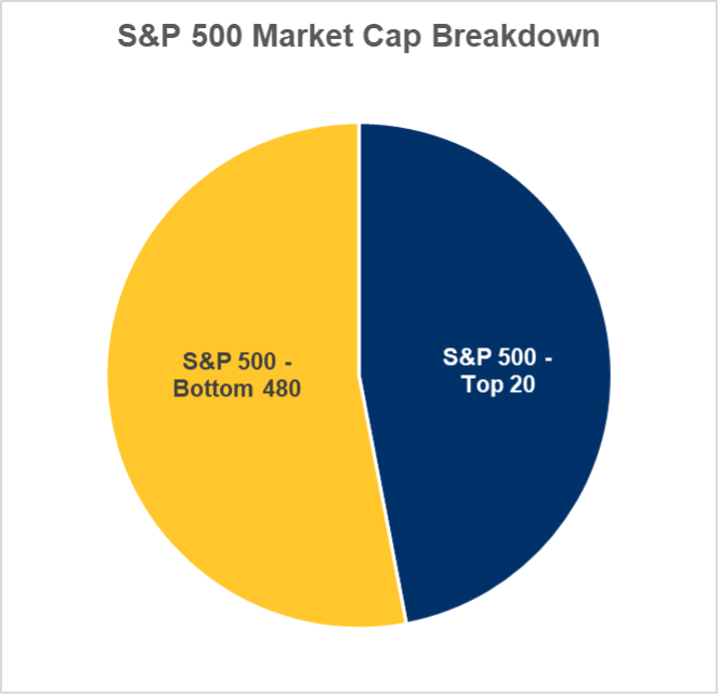

One of the points we (and many others) have consistently addressed in recent years is our concern about the increasing levels of sector and geographic concentration in the US stock market. Coming into 2025, nearly half of the S&P 500’s total market cap consisted of just the top 20 largest companies, with 38% being concentrated in the top 10.

Chart 4: The S&P 500 is extremely top-heavy and lacks true diversification

Source: S&P, Bloomberg

Decades of US trade deficits saw foreign firms selling goods in USD then recycling those dollars back into US assets: this has led to strong US stock outperformance relative to the rest of the world, but it’s also left us with an extremely top-heavy market. This effect is further intensified by the fact that the largest US stocks are all technology companies at their core, meaning there is a very high degree of correlation among them (they tend to move up and down together). This change has created the illusion of diversification in US stocks – it’s true that someone holding the S&P 500 has a small stake in 500 companies, but in reality the overall performance of this index will be predominantly dictated by a single trade: US tech.

What this means is that the global market has not only drifted toward a highly disproportionate weight in US stocks, but those US stocks themselves are very top-heavy in what is essentially a single, highly correlated trade. This leaves investors particularly vulnerable to any change in the prevailing winds.

To continue with our sailing analogy, this phenomenon can be thought of as “leeway”, which is the degree to which a boat veers off-course, particularly when a ship is sailing into the wind. True to the analogy, the periods where this “leeward drift” sting the most are when economic winds shift from tailwinds to headwinds.

Investor psychology also plays a significant factor here. FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) is a powerful force in the human mind, and many investors have piled into the US tech trade in recent years because it’s been the best performing sector over the last 10 years. However, a solid winning streak is no guarantee of future success; if it was, investors could simply put their retirement savings into Domino’s Pizza (one of the best performing major stocks since the GFC) and call it a day. Of course this would be an extremely risky bet, because what matters in investing is the future, not the past.

For these reasons we think it’s critical to course correct when the ship drifts off course, and we view true diversification through global stock allocations and off-index sector weights as key components of mitigating downside risk.

Taking the Helm

It’s easy to agree that avoiding downside is desirable, but in reality the risk of a decline in stock prices cannot be eliminated. Nonetheless, it can be mitigated, particularly by avoiding the names with the most speculative valuations where there is the furthest to fall.

To explore this concept further, consider a stock’s price as consisting of two components: 1) current profit, and 2) a company valuation multiple of that profit (put another way, earnings and P/E). Imagine you are considering buying one of two private companies that both currently generate $1 million in profit annually. One is a small dry-cleaning chain whose sales have been stagnant, and the other is a software start-up that has recently turned its first profit and is expected to grow sales rapidly.

Even though both businesses enjoy the exact same current profit, the amount you would be willing to pay for each is vastly different. You might be willing to pay $100 million (100x multiple) for the start-up, but only $10 million for the dry cleaner (10x multiple).

This multiple, or valuation, is crucial to the ultimate performance of each business. Despite shrinking sales, the dry cleaner could very well outperform the software company if sales decline more slowly than expected, or if the software company’s sales do grow quickly but not enough to justify the significantly higher multiple.

High multiples are not inherently bad, and are usually justified to some extent. The danger is that when an economic shock inevitably arrives, these are the names that have the furthest to fall, since the vast majority of the company’s value is derived from expected future profit rather than current profit. This doesn’t mean we avoid high-multiple, high-growth stocks by default, but it does mean we have a higher bar for these investments given their more vulnerable position in downturns.

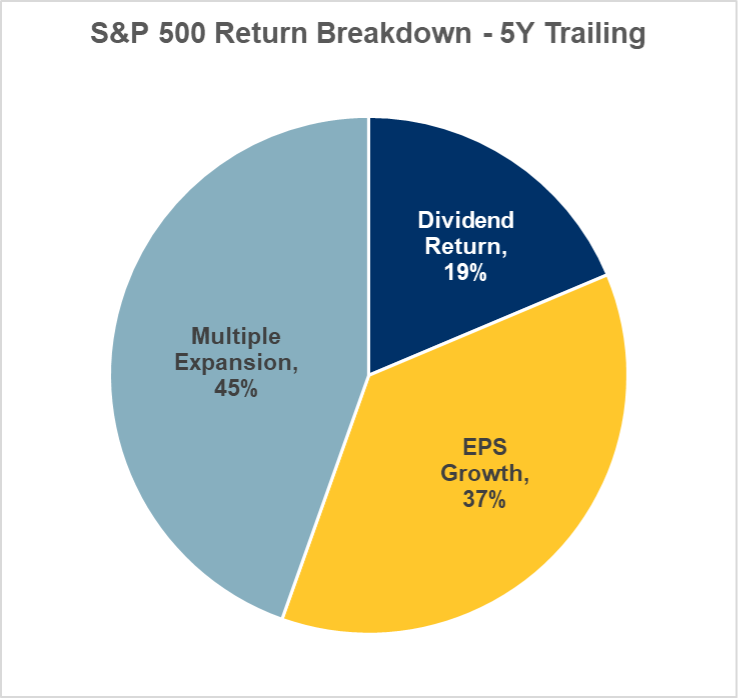

US equities in general have seen substantial multiple expansion since 2020 – the increase to the average stock price from 2020 through 2024 greatly exceeded earnings growth. Since multiple expansion is more speculative and volatile in nature, we view the historically high multiples in US stocks as a key source of vulnerability, and take great care to avoid stocks where price growth has significantly outpaced earnings growth.

Chart 5: Less than half of the S&P 500’s return since 2020 has come from actual earnings growth

Source: S&P, Bloomberg

There’s also a significant and growing part of the market that trades in a way that we view as completely detached from business fundamentals. These are often called meme stocks, with smaller names such as Gamestop or AMC or Hertz coming to mind. In one case recently we looked at a stock with consistent 5-7% sales growth trading at a multiple of 57x(!) – a valuation that is virtually impossible to justify at those levels of growth. In another case a very large company posted disastrous quarterly earnings where profit fell over 70% and sales declined far more than expected, yet the stock price jumped 25% in the proceeding three days.

Financial media analysts will always find ways to justify these price movements because it’s their job to do so, but this doesn’t change the reality that it’s no longer uncommon to see penny-stock levels of volatility among many large cap companies. In our view, this disconnected performance is due to a rise in the “gamblification” of investing that many investors are drawn to. If it doesn’t make any sense when a stock rises in value, it doesn’t have to make any sense when it drops either.

The reality is that many names in the market are valued on sentiment, momentum, and hype rather than business fundamentals such as profit, growth, margin, and competitive position. Investing in the former can be fun, but it’s dangerous; their valuations are not on solid ground, and the inevitable bear markets that come around every few years tend to disproportionately punish the stocks that have no profit fundamentals to fall back on.

This is why we feel so strongly about making a distinction between between speculation and investing: we want our clients’ portfolios to outperform because they are invested in superior businesses that are growing profit and cash flow sustainably, not because they happen to be the hottest topic on Reddit.

Conclusion

In Storms and Sunshine we argued that the best path to outperformance over the long run is to avoid the most extreme negative outcomes. In Resist the Siren’s Call we made the case that a decades-long drift in sector, geography and stock concentration has left most investors particularly exposed to economic shocks (such as tariffs). And in Taking the Helm we outlined our view on how to address this over-concentration and focus on fundamentals rather than speculation in order to mitigate the most extreme downside events.

Punishing storms are inevitable, and already in the first half of the 2020’s markets have had to navigate three unique varieties of dangerous economic weather. History has shown that these recurring storms are particularly painful for the more speculative, sentiment driven part of the market. We believe it’s in our clients’ best interests to avoid the disproportionate downside and volatility of speculative investing; in contrast, our objective is to protect the ship by focusing on business fundamentals, and to pull in the sails and reach for the oars with true diversification and defensiveness when the horizon darkens.