In the year Nineteen Hundred and Eighty-Five, Madonna was a veritable meteor. Fresh off her eponymous 1983 debut and her follow up 1984 double-diamond (20 million+ copies sold) Like a Virgin album, the self-proclaimed Queen of Pop (and who are we to argue) was the female and rock and roll answer to Michael Jackson. In addition to her soaring music career, in ‘85, Madonna would appear in two movies – the first, Vision Quest, a Rocky-style tale of a high school wrestler named Louden Swain who trains to take on the undefeated and seemingly unbeatable state champion. In the film, Madonna plays the lead singer of a bar band and while she has no lines in the film other than the two songs she sings (one – Crazy for You - would go on to become a monster hit), she figuratively steals every scene in which she appears with her mere presence (for the record, Vision Quest is a banger and well worth watching).

The second film – Desperately Seeking Susan (we will shorten to DSS from here on)– is the somewhat silly tale of a married woman who becomes obsessed with an ad in the personals section of the newspaper (for those not familiar – we used to have printed newspapers and a section in which people could post personal ads for stuff such as weed whackers and love connections (sometimes in the same ad – Have Weed Whacker/Seeking Love)) and eventually obsessed with a woman (Susan, played by Madonna) “sought” in one of the ads (hence Desperately Seeking Susan).

Now, this is a film that really has no business being good – sort of akin to making Ernest Goes to Camp because you want to make a movie featuring Jim Varney and the character of Ernest P. Worrell is the only way you can figure out how to do get Jim Varney into a movie (for the record, they made eight other Ernest movies including Ernest Goes to Africa, which we imagine might have stepped over a few lines). However, not only is DSS earnestly good (see what we did there?), but it was so good that it not only made the New York Times’ 10 Best List for 1985, but it also made Madonna an even bigger star than she was (which was not easy in 1985).

Around the same time as Madonna’s star was beginning to burn brightly, Canada was going through a troubled time. Inflation and interest rates were sky high, and the government was running large budget deficits (generally the opposite of what one wants to do when inflation and interest rates are too high) and championing policies that were perceived by many as restrictive to growth, including high tax rates and curbs on wage increases (nothing incentivizes work and effort like wage caps).

It is here that we segue to Canada’s current plight and the budget that was released on April 16th.

Desperately Seeking Fiscal Sanity

The venerable Jim Grant, who has published Grant’s Interest Rate Observer for more than 40-years, had a recent piece entitled “The inflation we choose”. The piece, which is about the U.S. fiscal situation, discusses how fiscal policy and more specifically a lack of fiscal restraint when the economy is in okay shape, ultimately gives us inflation. This inflation occurs especially in the places that we do not want it to occur – namely stuff such as food or eventually in higher interest rates because when the inflation candle is lit by too much spending, the only way to umm, un-lit it, is to keep interest rates high. Mr. Grant describes it as “the inflation we choose” because too much government largesse when largesse is not needed is a choice – not just the government’s choice; although, obviously the choices of our leaders play a role, but also the choice of the electorate – not only for electing said leaders, but also for “throwing a fit” every time it is suggested that spending reductions for popular programs be implemented.

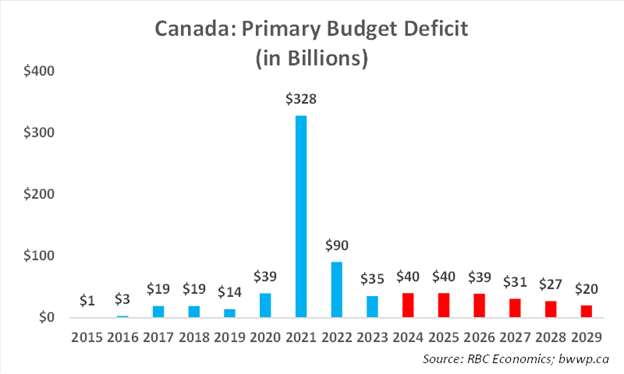

Going a bit beyond Mr. Grant’s piece, Canada released a budget last week, which purports to have largesse as far as the eye can see:

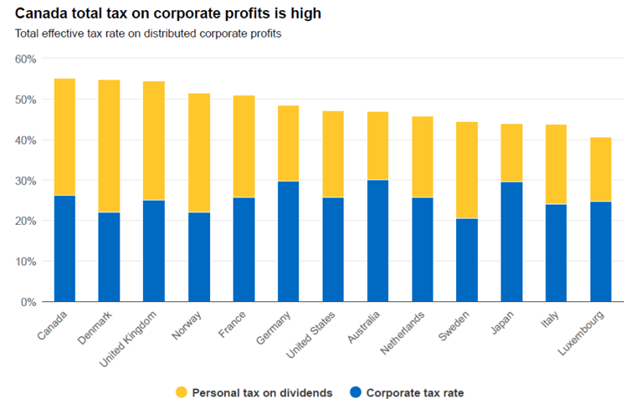

While the deficits are worrisome and potentially counterproductive to the Bank of Canada’s goal of bringing down inflation, they exist in a budgetary framework in which the government continues to push the envelope of taxes. In other words, these deficits would be even worse were it not for continuing to tax Canadians at rates that are significantly higher than most other countries:

As part of the budget, the government introduced a new 66.67% inclusion rate for capital gains. Individuals are exempt from the first $250k in which the current 50% inclusion rate still applies, but corporations will pay the higher inclusion rate on the first dollar of gains. Now, big business will likely not be affected by this change. In other words, the Royal Bank of Canada is not going to owe more tax because the capital gains inclusion rate is higher as this is not how the Royal makes its profit – although, if you are a PR person for the government, you might try to “sell it” to the public in this way. Rather, the new tax is going to capture small businesses, doctors, lawyers, and entrepreneurs who incorporate. The question in our eyes would be - is this productive for the economy?

An Economy that has been “Unproductive”

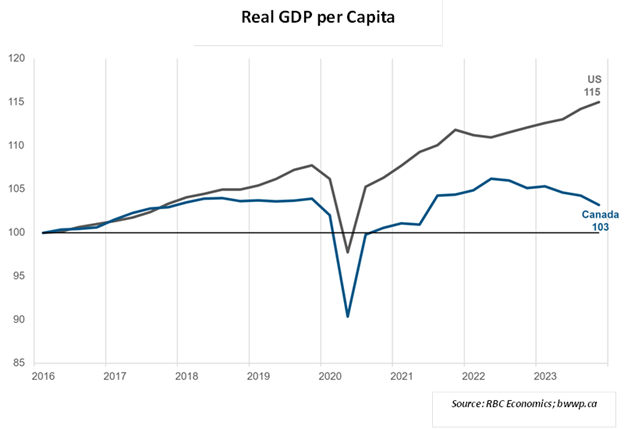

Generally speaking, higher taxes, especially when they are taxes on capital, do not improve the productivity of the economy. The simple reason for this is that higher taxes on capital discourage investment and the main way to improve productivity (output per worker) is to invest in new equipment and technology. Now, if Canada were coming from a position in which productivity growth had been robust, higher tax rates on capital would be bad, but manageable. But, as the chart below shows, this has been far from the case:

For lack of a better idiom – Canada has been stuck in the mud. Raising the inclusion rate on capital gains for corporations (and to a lesser extent individuals) is likely to make the above even worse with Canada staring at the real possibility that GDP per Capita could outright decline over a 10-year period, which is similar to what Japan has been grappling with for the better part of three decades.

We wrote a piece last month entitled A Re-call to Arms in which we outlined a series of steps we believed Canada needed to take to get the ship turned around. Needless to say - we did not have the above in mind when we wrote it.

Investment Implications: When is All the Negativity Priced In?

The above is obviously not positive from an investment perspective. Capital investment is unlikely to return to Canada and thus the overall economy is likely to stagnate, especially considering interest rates that remain at restrictive levels. But … here is where we are going to pivot slightly. The negativity toward Canada is at extremes we have rarely seen in our careers, which gives us a bit of comfort.

Why? Generally speaking – when all investors believe a certain thing, the opposite thing is likely to happen. Back in the early 2010s when we were presenting to client groups, we used to come to what we termed “the tomato throwing part of the presentation”. This referred to the following:

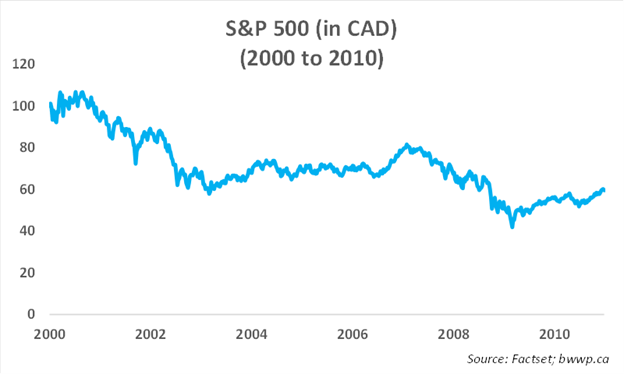

Over the decade from 2000 to 2010, Canadian investors (when the strength of the Canadian dollar is included) lost ~40% on their U.S. investments. Meanwhile, the Canadian market added ~60% over the period, accounting for essentially a 100% difference in relative performance for the decade. We called it “the tomato throwing part” largely because we thought it was exactly the right time for Canadians to look at U.S. investments, which generally made them want to throw tomatoes at us. The thesis for this was based on valuations in the U.S. that had largely compressed over the decade and an economy that was starting to gain some traction following the Great Financial Crisis. The U.S. story was not perfect at the time, but if you wait for perfect, it is generally too late.

Fast forward to today and we have seen a similar disconnect in performance, albeit in the other direction:

Now, we don’t have quite the passion for this contrarian call that we had back in the early 2010’s for the simple reason that there is currently nothing on the near-term horizon from a Canadian perspective to get excited about. Yes, interest rates are likely to come down as the Bank of Canada begins lowering rates this summer, but with the new budget just tabled, the economy is likely to be shackled even if it is getting some stimulus from interest rate relief.

That said – we could author the following story (note: we do not wish to be political here, but rather just convey a potential outcome):

- Interest rates start to come down driven by Bank of Canada rate cuts – the Canadian stock market is generally very positively correlated to lower interest rates because of its heavy weighting in Banks, Utilities, Pipelines, Real Estate and Telecommunications;

- The economy gets some relief from lower rates, especially given the sensitivity of housing to mortgage rates;

- While we are not big fans of the budget, there is significant spending on the housing stock within the budget, which should provide some economic stimulus;

- Given current polls, which appear to favor a Conservative majority in 2025, investors begin to price in a change in government and the potential for fewer regulations, lower tax rates and a more business friendly environment;

- Given lower than historic valuations, should the above unfold in some form or another, the “air above” current valuations leave significant room for expansion.

Ultimately, we focus on owning good businesses, whether in Canada, the U.S. or elsewhere. That said – our Canadian “good businesses” have generally been a struggle for the last couple of years, so the above is helpful to our thesis for owning them, even though we ultimately expect strong fundamentals to overcome economic and interest rate headwinds.