Back in February of 2017, when I was Chief Canadian Equity Strategist for RBC Capital Markets (yes – this is a humble brag and we are not proud of it, but we struggled to come up with a proper segue that did not sound like preening in some way), our team penned a piece entitled “A Call to Arms” (attached for anyone who wants to give it a read). In it, we pointed to a challenging economic landscape for Canada as the commodity boom of the early 2000’s had faded, while mistaken policy decisions and a general lack of economic creativity had failed to establish new potential catalysts for the coming years.

With the election of Donald Trump in 2016 (and the potential this could happen again), we feared that Canada could be left behind the U.S. from an economic perspective as a move by the U.S. to reduce taxes, cut red tape and erect trade barriers would not only hurt Canada’s relative competitiveness, but also potentially restrict Canada’s exports to the world’s largest economy.

We did not believe at the time that it was too late for Canada to pivot, but we did fear that leadership was potentially asleep at the wheel, content with fighting yesterday’s battles as opposed to preparing for the coming challenges and looking for ways to set Canada up as an economic titan for the future.

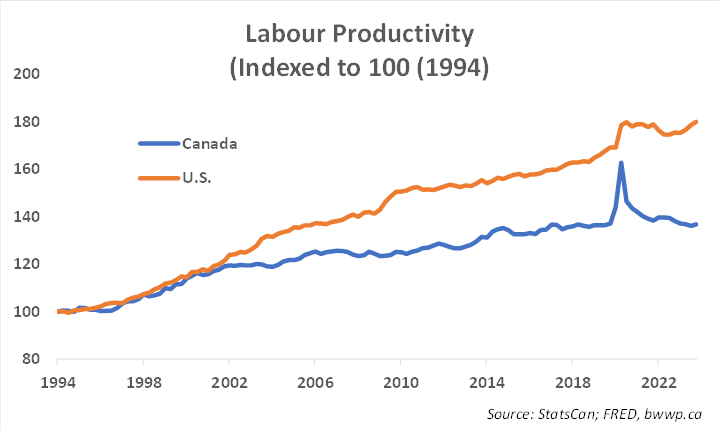

Fast forward 7-years, and frustratingly, our thesis has largely played out. While there is no perfect gauge for making this point, let’s start with a chart that we believe captures the challenges that Canada faces:

The good news is – Canada has all the pieces necessary to get there – fiscal wriggle room, an immigration plan that with a few tweaks would be able to provide the needed labour, and natural resources in abundance. Altering the course for the economy will not be easy, but moonshots never are. It is our hope that 7-years hence, we are looking forward to a brighter future.

Productivity measures the amount of economic output that workers produce per hour worked. While imperfect, productivity is perhaps the best gauge of how equipment and technology investment (the “industrial base”) interact with the workforce to give an indication of how much output the economy can get out of its workforce. The more investment that is put into the industrial base and the more training that is provided to the workforce, the higher one would expect productivity to be.

As you can see from the chart, while Canada mostly kept pace with the U.S. into the mid-2000s, the two economies have sharply diverged over the past 15-years with the post-COVID years seeing an accelerated divergence.

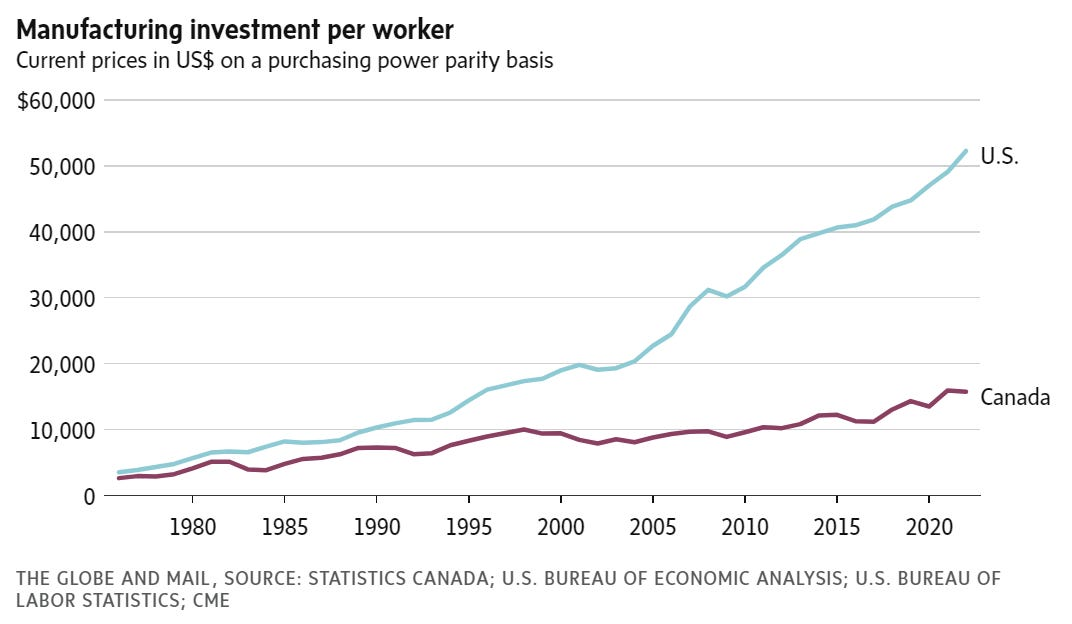

To put this chart in some perspective, the average U.S. worker produces ~80% more per hour worked than the average U.S. worker did 30-years ago. For Canada, the change is ~35%. And while the knee-jerk reaction might be to indict the average Canadian worker, the much bigger driver is investment in the industrial base, which has been lacking in Canada for decades:

The U.S. invests ~$50k per worker whereas Canada is closer to $15k. And while this dichotomy has existed for a long time, once again the divergence has accelerated in the past decade.

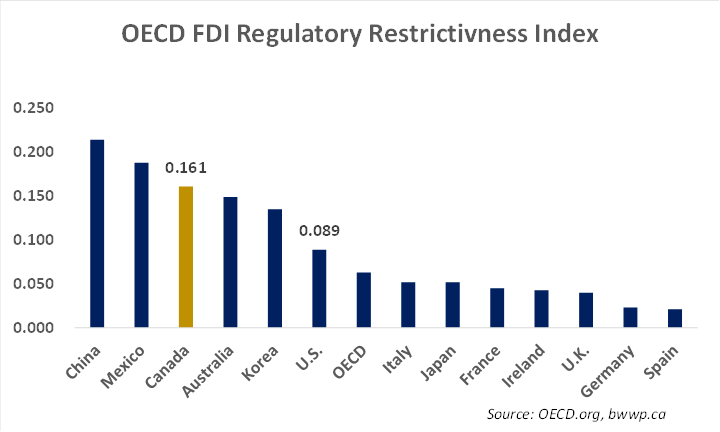

There are multiple drivers of this, we would note (as we did back in 2017) that Canada continues to put up barriers to foreign direct investment (FDI), which, along with government investment, is key to expanding the industrial and technology base:

Canada currently ranks 3rd worst amongst developed economies in the level of barriers to FDI with barriers at about twice the level of those in the U.S. We argued back then and would argue it again here - if you are situated next door to the 40k pound gorilla, taking steps to make yourself as open as possible to attracting investment dollars would be a prudent economic decision in our view.

Canada: Still a U.S. Story

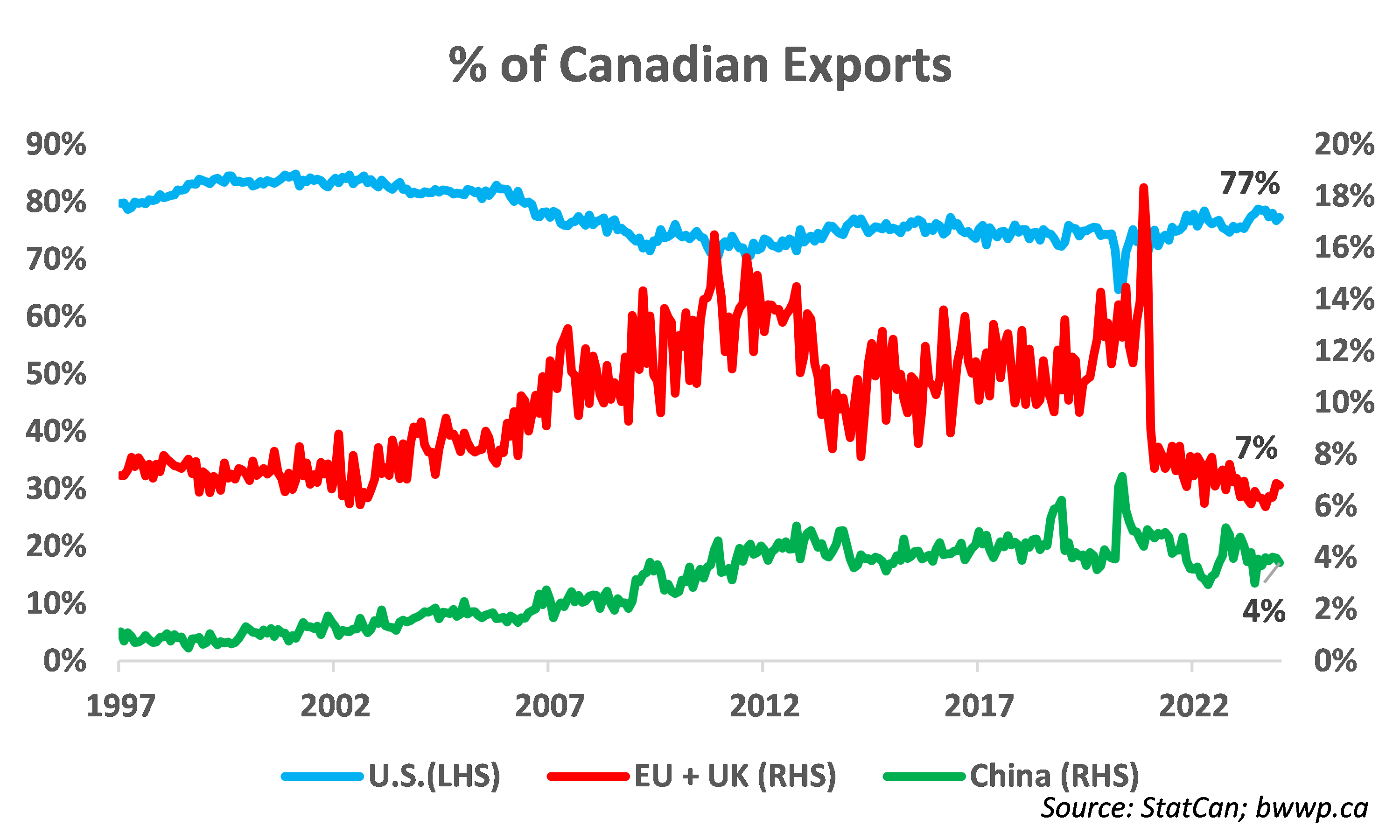

We argued back then that Canada should be focused on diversifying its economy so that it was not so reliant on the U.S. Part of this was a reaction to Donald Trump and his “America First” mantra and part of this was a response to the simple math – with ~75% of Canadian exports going to the U.S., the upside for Canada likely lay outside of its Southern neighbor. Unfortunately, as the chart below demonstrates, little has changed over the past 7-years:

The U.S. still accounts for ~77% of Canadian exports (up a couple of percent over the past decade) with Europe and China mere afterthoughts. With a non-zero probability that Donald Trump is re-elected in November (please do not shoot the messenger), Canada may once again be faced with heavy reliance on the U.S. and a U.S. administration that is hostile to trade.

Five Areas of Focus

While not necessarily a definitive list, we believe that there are five areas that Canada should focus us to set the economy on a better long-term path.

Focus #1: Barriers to Investment

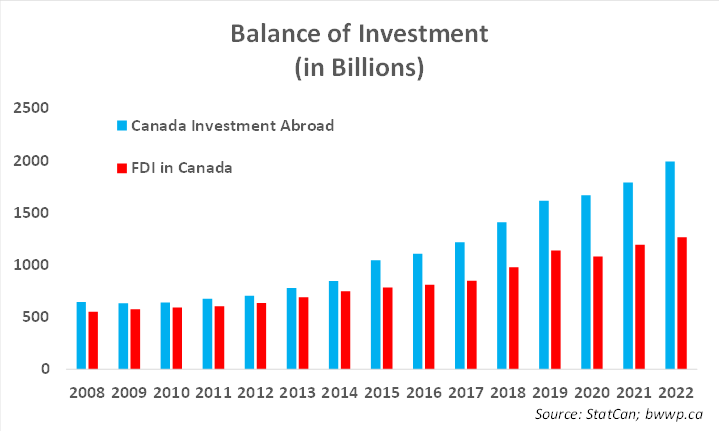

Canada does not rank particularly well on the FDI front. Changes to the Investment Canada Act in 2012 made it more onerous for foreign entities to invest in Canada. While FDI has risen in recent years, it has been far outpaced by Canada’s investment outside of Canada (essentially Canada’s version of FDI).

Think of the above chart this way – Canada is generally finding better investment opportunities outside of Canada than foreigners are finding within Canada. In 2008, the two metrics were essentially balanced at around $500 billion. In 2022 (the last year for which we have data), Canada was investing ~$700 billion more outside of the Country than foreigners were investing in Canada. Even without potential challenges to trade with the U.S., Canada’s focus should be on figuring out what is restricting FDI (likely a combination of too much red tape, taxes, and access to labour) and putting together a comprehensive plan to improve it.

Focus #2: Housing Availability and Affordability

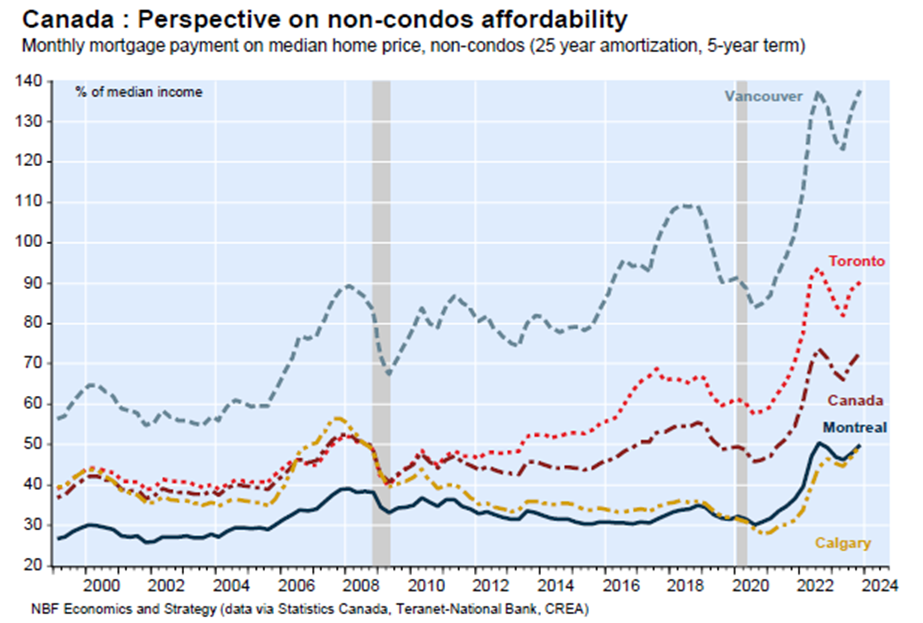

We have discussed this at length in prior missives, a barrier to investment in Canada likely has some relationship to the high cost of living in Canada. While Canada has many regions in which housing affordability in not a big issue, the bottom line remains that a high percentage of new immigrants locate in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) and most FDI outside of that which goes toward commodities, is targeted toward Ontario.

Not to sound like a broken record, but Canada needs a plan to increase the housing supply and improve affordability in Ontario and the GTA. This involves not just removing red tape (Focus #1), but also looking to increase the available labour pool for the construction industry.

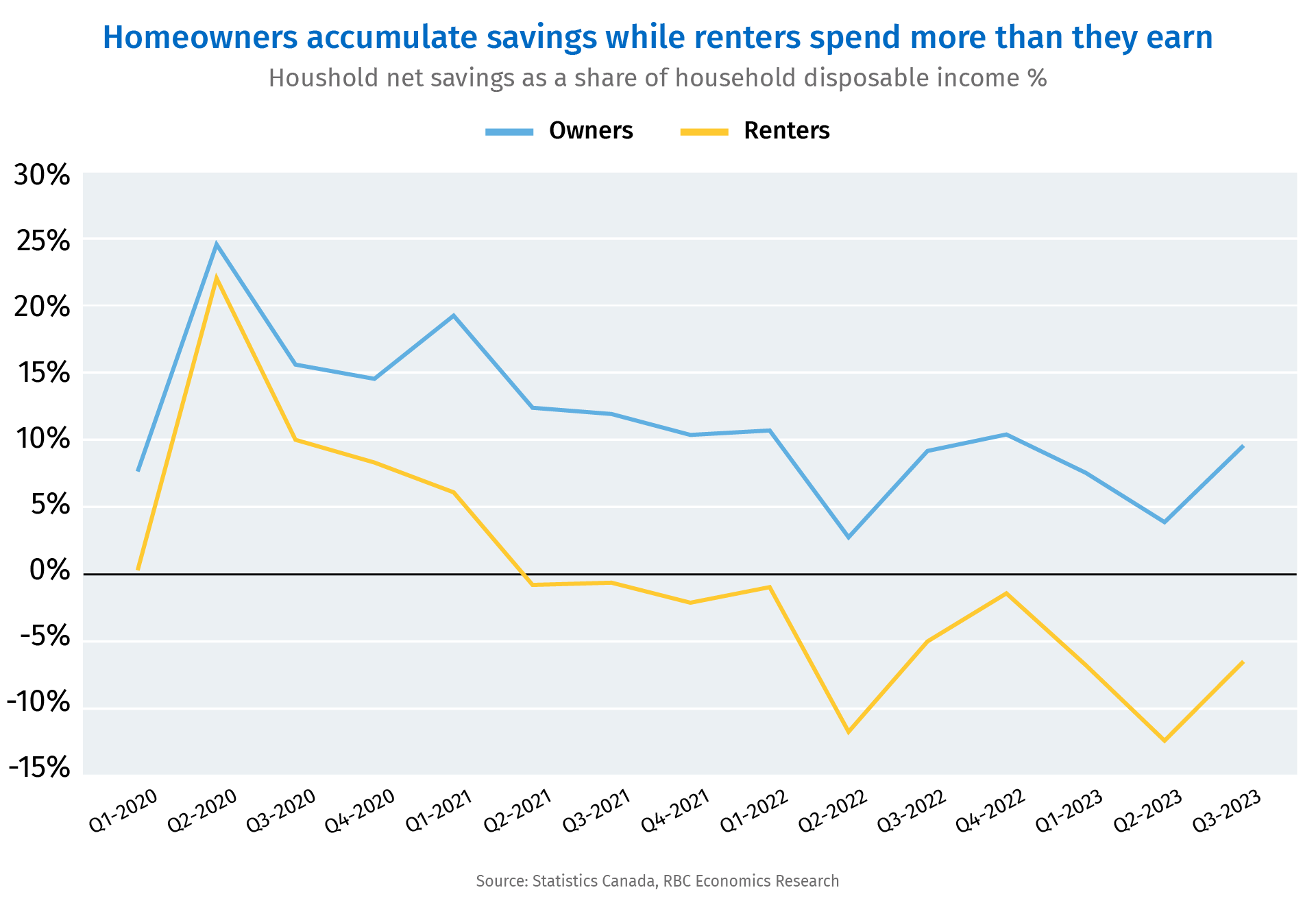

The current housing situation is leading to a broadening dichotomy between the haves and have nots in the country. RBC Economics notes that in the past 20-years Canada has seen a shift from ~50% of Canadians earning enough to purchase a home on their incomes alone to ~33% currently and significantly lower percentages in key markets such as the GTA and Vancouver. This has helped to contribute to a sharp rise in rental costs, which has led to the following disturbing trend:

For the better part of the past 4-years, the average renter has generated negative net savings, which essentially puts home ownership further and further out of reach, as savings is required for a down payment.

Focus #3: More Targeted Immigration

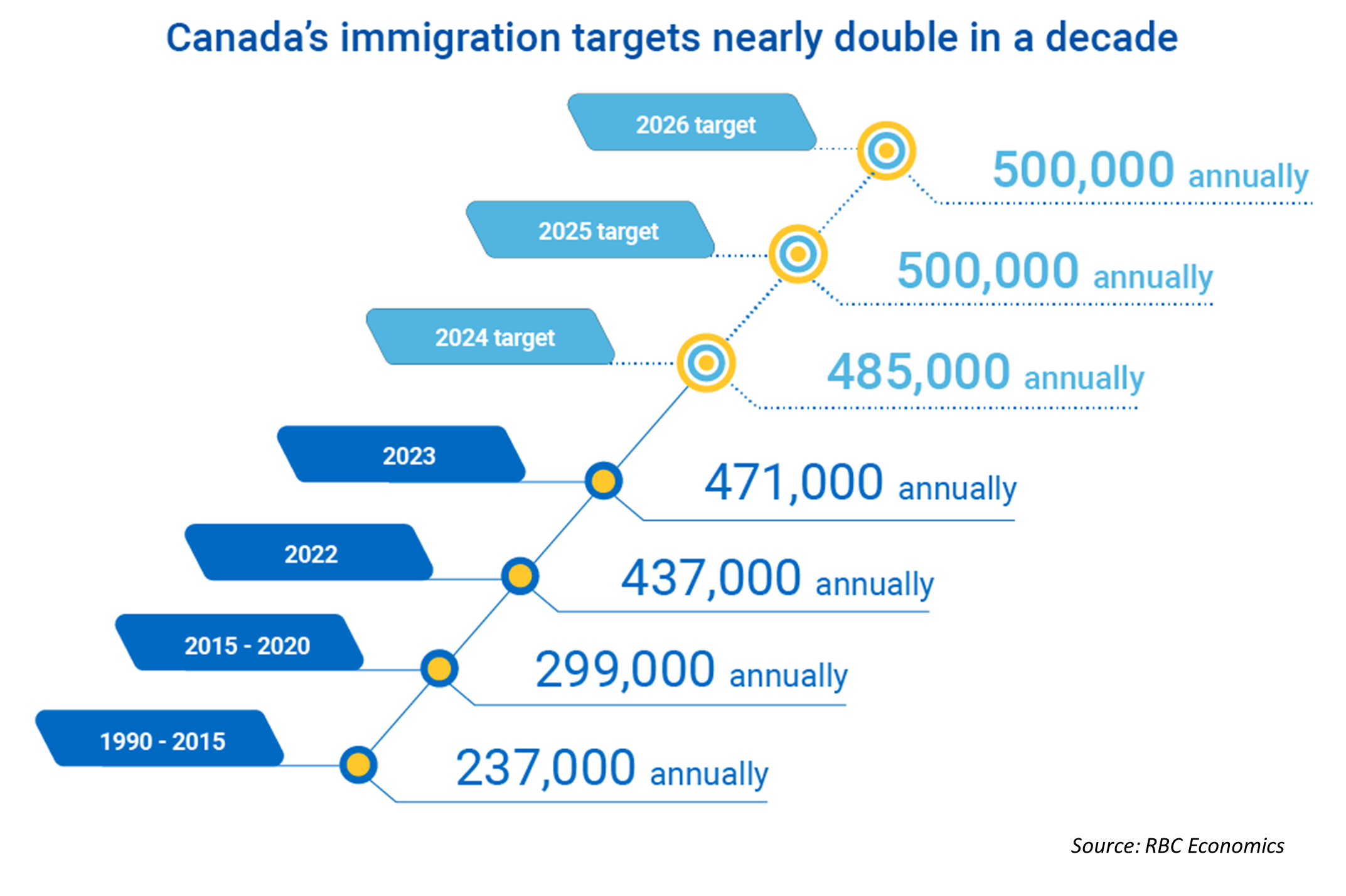

We remain very big supporters of Canada’s overall immigration strategy. Birth rates among developed nations are well below replacement level and Canada is no exception, sitting at ~1.40, which is well below the ~2.0 threshold needed to maintain population levels in the long-term. A robust immigration strategy is needed to offset this low birthrate and Canada has certainly embraced this over the past decade. According to RBC Economics, Canada’s population grew 3.3% for the 12-months ending July 2023, which was the highest annual growth rate in more than 60-years. Further, Canada has robust targets for the next several years as well:

However, our one complaint would be that Canada’s immigration strategy has lacked the focus required for the Canadian economy. While immigration has provided ample supply of labour for areas such as food services and accommodations (areas where there were acute shortages of labour coming out of the COVID lockdowns), other areas of the labour market such as skilled trades are suffering for significant labour shortages.

Returning to Focus #2, Canada needs a comprehensive strategy to build more housing, which inherently involves either bringing in and/or investing in education for skilled trades. Currently, there is no such strategy to do so, which is exacerbating an overabundance of available labour in certain areas of the economy and a lack of labour in others.

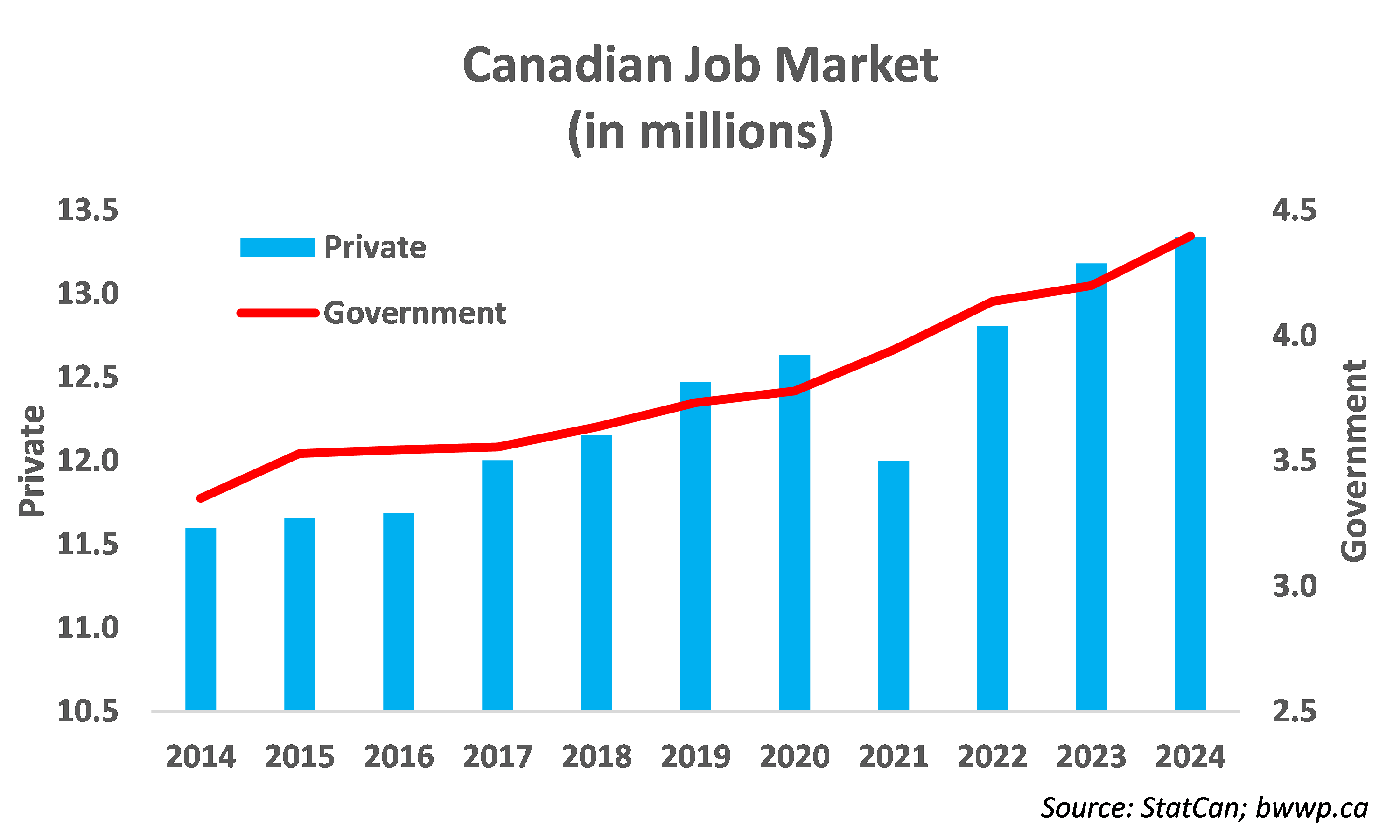

Focus #4: Downsize the Government

The other side of the coin as it relates to the lack of private investment is the ballooning size of the government sector. Nearly one in four Canadians that are not self-employed are now employed by the government, which is ~3% higher than a decade ago and about 10% higher than the United States. In fact, over the past decade, ~40% of the 2.8 million jobs that have been created in Canada have been government jobs.

Needless to say, this is likely not a sustainable dynamic as an ever-growing share of the tax base is required to fund an expanding government labour base. All levels of government should understand the burdens that this is putting not only on the tax base, but also the crowding out effect this has on private investment and the private labour base.

Focus #5: Moonshot!

As John Kennedy once famously said, “we choose to go to the moon … and do other things … not because they are easy, but because they are hard.”

Now, we are not in any way implying that Canada should attempt a moon landing in the next decade, but rather, the government should consider a long-term plan that focuses Canada’s resources on a great national endeavor. Become the world leader in clean energy technology, or build a great new industrial base, or build an array of modernized nuclear power plants to supply AI and Quantum Computing with the vast amounts of power they will need or leverage the vast oil sands and become the world leader in oil and gas production, or, well, you get the point.

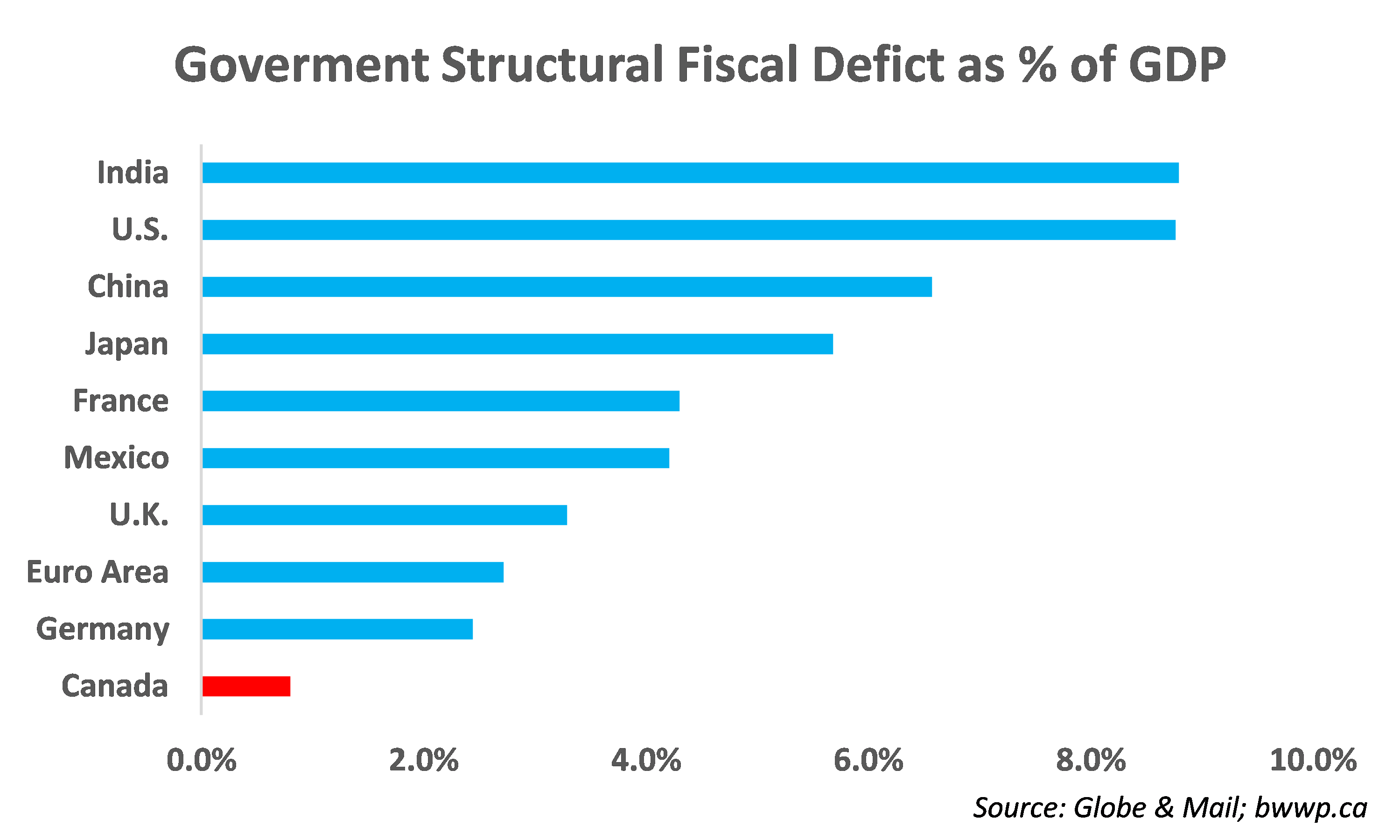

Canada is currently a mishmash of too much regulation, heavy tax burdens, Provincial in-fighting and project delay and indecision. A national plan to invest in something that will not necessarily have an immediate payoff but will have the potential to set up the economy for long-term success would be a worthy endeavour in our view. Further, we would note that unlike many other countries (including the U.S.) that are burdened by significant deficits at the Federal level, Canada continues to have a significant amount of “dry powder”:

Conclusion

Seven years ago, we wrote “A Call to Arms” as an appeal to the powers that be within Canada to set the country on a more sustainable economic path. Unfortunately, the past seven years have not been kind to the Canadian economy, which continues to generate negative GDP per capita growth and poor relative performance when compared to the United States. But, despite these lost years, it is not too late in our view for Canada to course correct and create a better and brighter economic future. It will not be easy, and it will require a political will that has been sorely lacking over the past two decades.

The good news is – Canada has all the pieces necessary to get there – fiscal wriggle room, an immigration plan that with a few tweaks would be able to provide the needed labour, and natural resources in abundance. Altering the course for the economy will not be easy, but moonshots never are. It is our hope that 7-years hence, we are looking forward to a brighter future.