Lincoln v. Douglas

The Presidential debating system traces back to seven separate debates over three months in 1858 between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas for a United States Senate seat in Illinois. The so-called Lincoln-Douglas debates became a national sensation (although for some reason they were not televised) with newspapers from around the country eagerly reporting the back and forth between the Republican Lincoln, who advocated for the end to the expansion of slavery (although, not the abolition of slavery) and the Democrat Douglas, who argued that slavery should be the choice of the new states joining the Union and not the Federal government.

Douglas would go on to win the Election (back then, state legislators picked their senators), but Lincoln would catapult to national prominence largely as a result of his debate performances. Just two years later, Lincoln and Douglas would face-off again, this time for the U.S. Presidency; although, they would ironically not hold any debates in the lead up to that Election. More than 81% of the U.S. electorate would cast a vote in the 1860 Election (the second highest percentage ever) and Lincoln, in a race that had several third-party candidates, would receive ~40% of the vote. However, because he was not even on the ballot in 10 southern states (let’s just say that while we think things are pretty bad today – 1860 just said “hold my beer”), his share of the popular vote total in which he had access was actually well above 50%. As a result, and because of Electoral heavy states such as New York and Pennsylvania, Lincoln would go on to win the White House by a fairly comfortable Electoral College margin. Interestingly, while Douglas would win the second highest popular vote total (~30%), he would go on to finish fourth in the Electoral College largely because of how the southern states split their votes.

And then a century passed

Believe it or not, it would take another 100-years for the first actual Presidential debate to be held – this time between Democrat John Kennedy and Republican Richard Nixon. The first of these debates is less remembered for the actual content and more remembered for Nixon’s gaunt appearance (he famously eschewed make-up for the television cameras), which cast the more photogenic Kennedy (number one ranked in our Presidential “hotness” rankings) in a much more favorable light. Polls would flip soon after the debate and Kennedy would go on to win a narrow victory in the Election (tragically, Nixon would come back).

The debates would not become a regular thing until 1976 when Republican Gerald Ford faced Democrat Jimmy Carter in a series of debates (fun fact – every Democratic President to serve since the Beatles broke-up is still living today). All Presidential elections since 1976 have included at least one debate with all of these debates held beginning in late September of the Election year. That was until, of course, 2024 when Joe Biden and Donald Trump agreed to debate in June of this year, which inexplicably pulled forward the debating schedule (as we have noted previously, if the 2024 debates had followed the “normal schedule”, Joe Biden would almost certainly be the Democratic candidate over Kamala Harris as it would have been too late to replace him on the ballot).

Harris v. Trump Debate

Here were some take-aways from the debate in case you missed it:

- We had always understood the term “asylum seekers” to mean those seeking protection; however, it may actually mean those who have escaped or been released from insane asylums (or at least one candidate seems to think it does).

- Under no circumstances, should you travel to Springfield, Ohio with your pets.

- Run, Spot Run is apparently not a book you should read – also, it is four sentences and not three words.

- If your name is Abdul and you live in Afghanistan, you may want to check your DMs.

- If you were playing Debate Bingo and you had Hungarian strongman Victor Orbán on your card – you were a winner.

Okay, with that out of the way, let’s look at some charts that frame the debate as it relates to the state of economic affairs at present:

The U.S. Economy Has Slowed …

Much has been written over the past few months about the slowing U.S. economy. We will not dispute that some slowing has occurred; however, we think the growing consensus that the U.S. is headed for recession greatly overstates the risks. Let’s start with jobs:

The 6-month moving average of job creation is down to ~160k, which is the lowest level in more than four-years. Further, the past 3-months have seen that average dip to ~120k. Now, while this slowdown is worrisome, it is worth noting that 160k is not far off of the average monthly job creation from 2010 through 2020 (pre-COVID) when jobs averaged ~190k per month. In addition, the Trump years, which were rightly celebrated as a strong economy (not the greatest ever as it was framed, but still solid), saw a monthly average (again pre-COVID) of 182k, which is a 0.01% difference in a workforce of ~160mn from where the 6-month moving average currently lies.

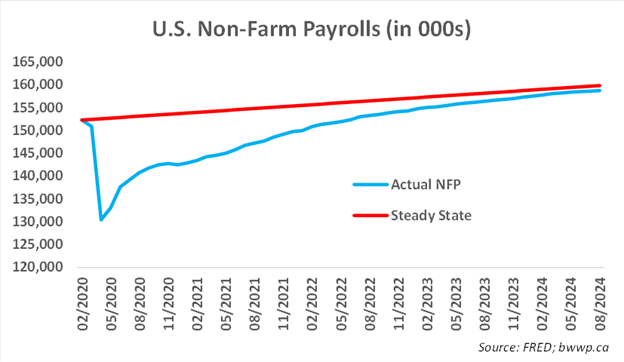

What the Pundits should be saying: The U.S. economy needs to create ~150k jobs per month to maintain a steady state of employment. This is because the U.S. creates ~2mn net new households per year through folks aging into the workforce (less those aging out) and through immigration. But, because of COVID, payroll numbers have been skewed for the last 4-years first to the downside and then to the upside. Another way to look at it would be to compare where the jobs market would be if COVID had never happened, and steady state job growth had occurred over the past 4+ years vs. where we actually ended up:

As you can see, after falling off a cliff during the COVID lockdowns, the jobs market first rapidly and then gradually converged toward its steady state growth. So, while the recent slowdown has raised some alarm bells, one could make the argument that the jobs market is finally, after 4-years, back to where it would have been absent COVID. In other words, a slowdown to something approximating steady state growth is neither unusual nor worrisome. Let’s pivot to a different way of looking at the jobs market:

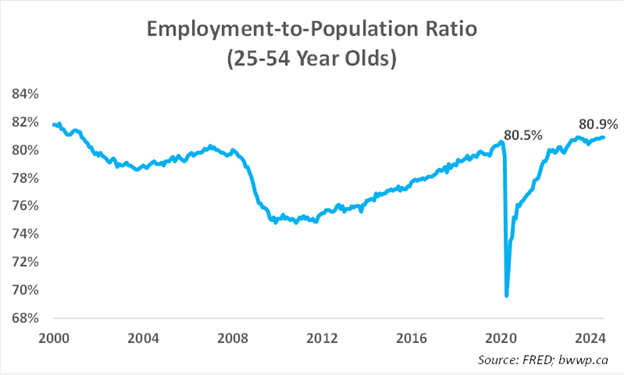

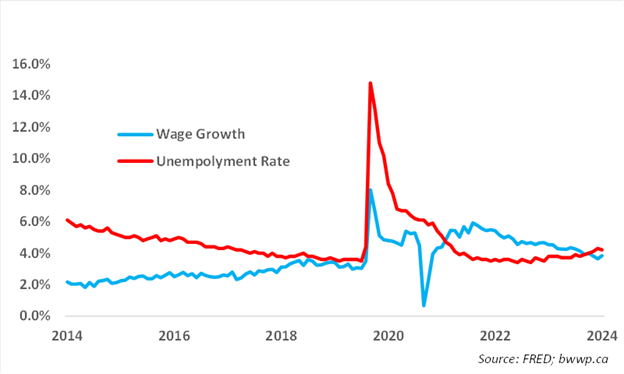

We highlighted this chart a few weeks back. While the overall job market has slowed, this slowing has mainly occurred at the fringes – with so called Prime Age Employment still hitting post-2000 highs. Further, while both the employment rate and wage growth are showing some signs of weakness, they remain at levels that are much more supportive of a soft landing thesis as opposed to a recession:

Unemployment has ticked up from the mid-3% range to the low 4% range. However, again, this is largely the result of an uptick in youth unemployment (15-24) as opposed to Prime Age. Further, while wage growth has slowed, it is still running close to 4%, which is ~1% higher than the 10-years prior to COVID.

Okay, let’s look at one more U.S. chart before pivoting to some charts on Canada:

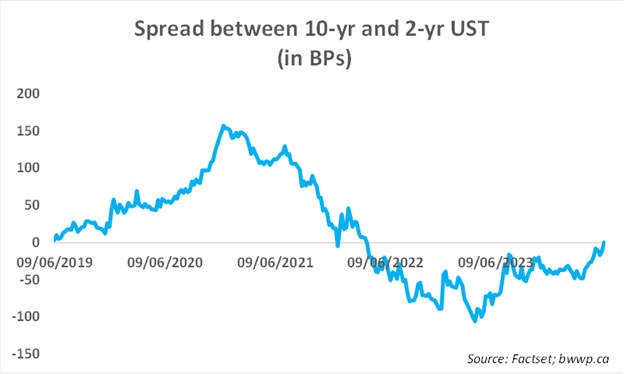

For the first time in roughly two-years, the yield curve has un-inverted with yields on 2-year bonds now marginally below 10-year bonds. As we have noted in the past, an inverted yield curve is indicative of an economy that is expected to slow down with recession risks considered high. A normal yield curve, in which short-term rates are below long-term rates is generally associated with a healthier economy, so it is nice to see normalization begin to take hold. That said- the yield curve was inverted for the better part of two-years, so normalization does not mean that the economy is necessarily out of the woods as it relates to recession risks.

Some Quick Canada Updates

Okay, we are going to pivot to Canada and first talk about something anecdotal, which is supportive of a piece on a potential redux of the housing bubble that we wrote late last year. We were having a chat with a friend who owns a mid-sized plastics business. One of their end markets in residential real estate and specifically pre-construction, which generally involves lots of digging to lay pipes and wires for the future community. He noted that the pre-con market was essentially non-existent for the better part of the past nine-months. Let’s now add a chart and then comment:

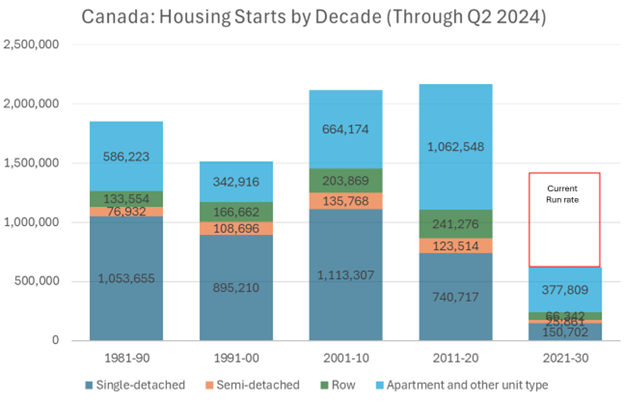

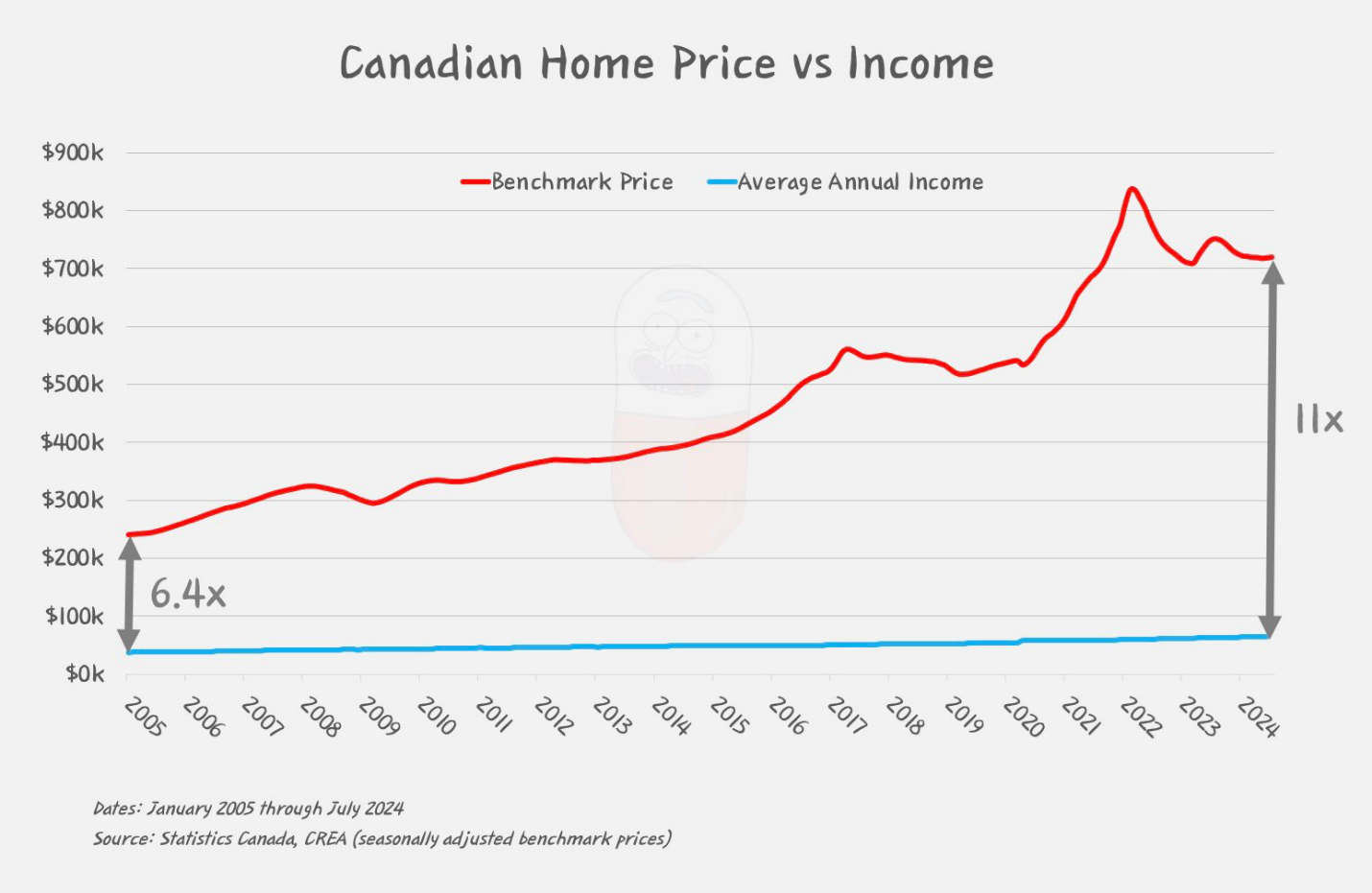

The above chart speaks to the conversation we had – Canada is falling far behind where it needs to be in terms of residential construction, which is going to create problems when demand comes back. While interest rates have come down, mortgage rates still remain at restrictive levels relative to pre-2022, but with the Bank of Canada likely to continue reducing rates over the next year (there have been three rate cuts already), mortgage rates are likely to begin stimulating demand at some point over the next couple of quarters. For now, the gap between home prices and incomes is unlikely to spur a near-term recovery:

While the gap is prices to incomes has narrowed over the past ~3-years, it is still nearly five multiple points higher than it was 2-decades ago. This is likely to get worse over the next few years as a combination of declining mortgage rates and pent-up demand that has built up over the past three years combine to drive prices higher. Okay, let’s pivot to the stock market:

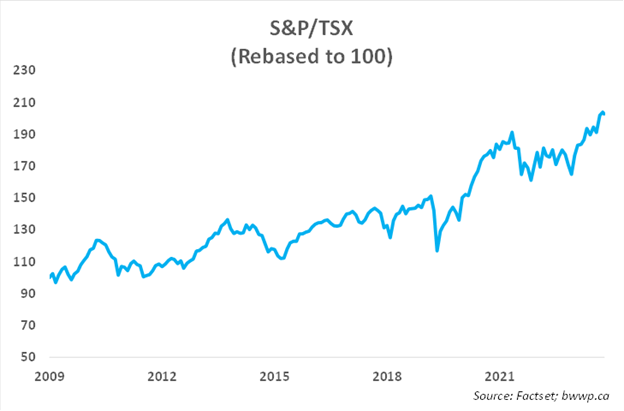

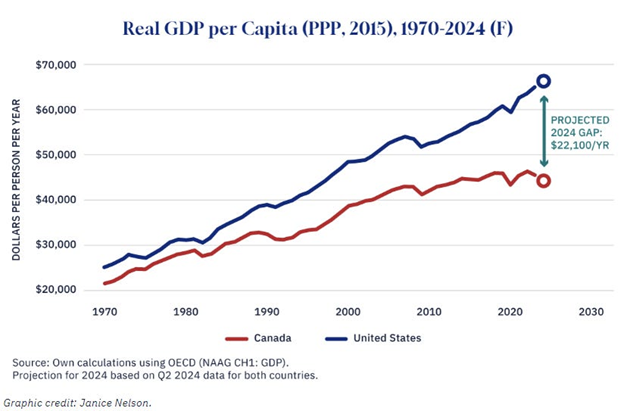

The S&P/TSX, despite a recent pullback, remains near all-time highs. While we do not wish to get political in any way, we would note that in our conversations with PMs and strategists – especially South of the border – we have begun to detect a bit more optimism toward Canada as it becomes more apparent that a change in government may be approaching. For the better part of the last 15-years, there has been a sense that Canada is not “open for business”, which has had a chilling effect on foreign direct investment and has greatly curtailed growth in Canada, especially on a per capita basis:

While Americans have always been more productive than Canadians going back to 1970, the gap as recently as 2010 was ~$10k. Since then, the gap has widened to more than $20, with the average American worker producing ~50% more than the average Canadian worker. Could lower interest rates and a warming of the investment climate begin to reverse this trend? We are not quite ready to declare that yet, but as mentioned, we do get a sense that a change in sentiment may be afoot.

Bottom Line: We apologize for the meandering nature of the above, but we had a fair bit on our minds. From debates to economics to a thawing in sentiment, there is no shortage of things to talk about and we suspect this will continue. Markets have been fairly volatile over the past couple of months and with the U.S. election looming, we would expect this to continue. Our view remains that the set up over the next 3-5 years remains good and if we get something more than very short-term weakness, we would probably look to allocate a bit more to stocks. Until then, we will hope for more debates simply for the entertainment value.