The rising economic clout of women is perhaps one of the most significant economic shifts of recent decades. Not only are women generating and managing an increasing amount of wealth, they are also directing the economy itself—heading up major corporations and pivotal economic players like the International Monetary Fund and (until recently) the U.S. Federal Reserve.

Furthermore, throughout the global economy, women are starting and running new businesses at a rapid rate. In the U.S. alone, women were majority owners of 9.9 million U.S. businesses of all sizes with more than 8.4 million employees in 2012, according to a 2016 report by the Small Business Administration.

These businesses generated US$1.4 trillion in sales. Another 2.5 million businesses were equally owned by women and men, had 6.5 million employees and accounted for another US$1.1 trillion in sales.

Coupled with the accumulated effects of five decades of increasing female participation in the workforce, this translates into real financial power:

- Globally, women held 30% of all wealth controlled by individuals or families in 2015, up from 28% in 2010; 44% had grown their wealth independently as entrepreneurs.

- By 2020, women are expected to control US$72 trillion, 32% of all wealth and up from US$51 trillion in 2015.1

In this context, The Economist Intelligence Unit undertook a study of high-net-worth women and men (individuals with US$1 million or more in assets), sponsored by RBC Wealth Management. The survey covered 1,051 individuals (502 women and 549 men) in Canada, the U.S., the UK and Asia (mainland China, Hong Kong, Singapore). (For more information, see the below chart, “Survey sample.”) What follows are key findings and insights about a growing and very diverse group of women who are fundamentally rethinking the meaning of wealth and giving and who are designing legacies that will affect the world the next generations inherit.

Survey sample

For this study, The Economist Intelligence Unit surveyed 1,051 individuals with US$1 million or more in investable assets, defined as excluding personal assets and property such as a primary residence, collectibles, and consumer durables.

The survey sample included 502 women and 549 men located in Canada, the U.S., the UK and Asia (mainland China, Hong Kong, Singapore). The Western markets encompassed 79% of the sample and Asia the remainder.

Women taking charge of their wealth creation

Our survey underscores the increasingly prominent role women are assuming in the high-net-worth universe and suggests their influence is likely to continue to rise given the number of younger women who see significant opportunities to generate wealth. Notably:

- Although there are still far more high-net-worth men than women, the proportion of the wealthiest women to men in the survey, those with US$5 million or more in assets, is roughly the same—27% men and 22% women.

- Millennial women (born 1981-2000) are entering the highest circles of asset ownership faster than women born earlier: 22% of Baby Boomer women (born 1946-1964) have $5 million or more in assets, while Millennials come in at 32%.

It’s notable that the share of men who think they have had more opportunities to generate wealth than people in prior generations, 83%, is only slightly higher than the share of women saying the same, 78%. Indeed, 21% of women with US$5 million or more in investable assets are owners/founders of a business, self-employed or entrepreneurs, as are 16% of HNW women with lower investable assets.

Exhibit 1: Opportunities to generate wealth

Percentage of each group who selected each choice (respondents could select up to three)

That correlates with the finding that younger women more often than older women say they’ve earned their wealth through business rather than inheritance. Half of Millennial women reported that they have gained their wealth through business, and half said they had inherited money. By contrast, more than half of Baby Boomer women (56%) say they inherited money, while only 37% say they gained their wealth through business.

Half of Millennial women created their own wealth

Women’s sense of where the opportunities lie for wealth generation differs by age as well. While Baby Boomer women identify resources and opportunities to succeed in the workplace as the key to wealth generation, younger women place more emphasis on resources that help them start successful businesses (Exhibit 1).

The geography of women’s wealth is diverse in the countries studied and varies according to levels of wealth. Levels of wealth vary by geography, with the U.S. accounting for the largest share of women with between US$1 million and $5 million in investable assets. Those with US$5 million or more in assets are more evenly distributed (Exhibit 2). (Articles exploring details on survey findings about each region can be found at www.rbcwealthmanagement.com/legacy.)

Exhibit 2: Distribution of wealth

Percentage of women in each category in each country or region

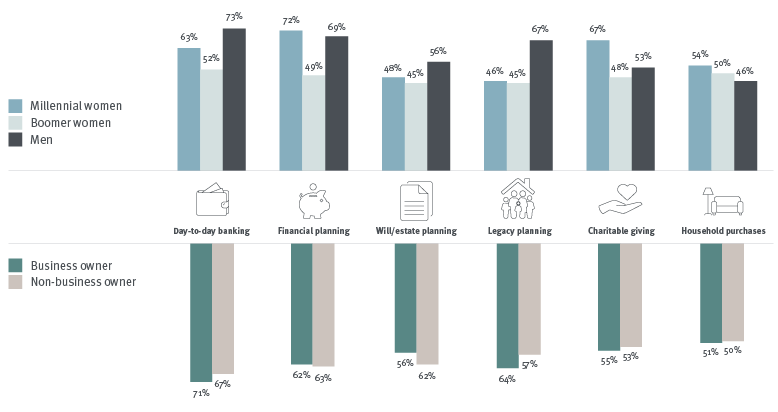

More women taking control of wealth and legacy decisions

As more and younger women earn more wealth, they are more often asserting themselves as decision makers over the full range of finance-related issues. One particularly notable finding is that less than half of Boomer women say they are their household’s primary decision maker for financial planning; for Millennials, the figure rises to 72% (Exhibit 3).

However, the survey found considerable variation based on the level of wealth. For every issue covered, from financial and will-and-estate planning to charitable giving, women with more than US$5 million in investable assets are more often the primary decision maker than HNW women with lower investable assets. The difference is wide when it comes to financial planning, where 69% of these women report they are the primary decision maker, compared with just over half of HNW women. Given the share of Millennial women with $5 million or more in assets, it’s likely that relative youth is one reason for this finding.

Women also differ as to whom they rely on for advice on wealth planning. Fifty-three percent of HNW women say their spouse or partner has the most influence, while 47% of the wealthiest women agree. Younger women, though they are just as often married as older ones, less often say their spouse has influence over their wealth planning than Baby Boomers, 41% vs. 54%. Forty-nine percent of men, by comparison, say their spouse or partner has the most influence on their decision making.

72% of Millennial women are primary decision makers for financial planning

Children become more important influencers as women age: 11% of Boomers cited them, compared with 7% of Millennials. Friends and peers, by contrast, decline in importance: 10% of older women cited them, while 26% of younger women did so. This may well be because Boomers’ children are more likely to be adults.

Although almost half of Boomer women cite financial advisors or planners as important influencers, compared with 37% of Millennials, the more wealth women accumulate, the less influence advisors wield, the survey suggests. Almost half (48%) of HNW women say they rely on a financial advisor/planner, compared with 42% of women with US$5 million in investable assets. Forty-four percent of men say the same.

Exhibit 3: Who's making decisions?

Percentage of each group who are the primary decision maker in each category

Younger women defining wealth differently

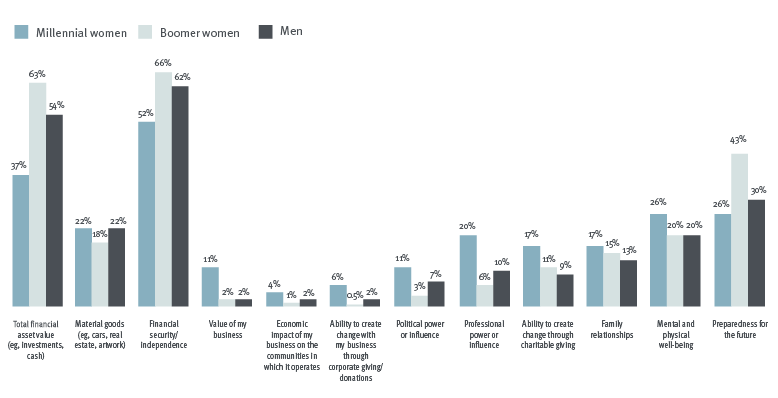

Given all the differences in HNWIs’ sources of wealth and how they make decisions about it, what we found notable is that few gender differences are evident in how they actually define wealth or life goals at a global level—though there are some striking differences by age.

Most often, HNWIs define wealth as financial security and independence, chosen by 62%, or total financial asset value, chosen by 54%. The only meaningful difference between female and male HNWIs in how they define wealth is that 38% of women include preparedness for the future in their definition, compared with 30% of men. It’s also notable that male and female business owners are about equal in how often they include the overall value of their business, the economic impact of their business on the communities where it operates and the ability to create change through corporate giving as part of how they define wealth.

As on many other issues, older HNWIs have very different definitions of wealth than younger ones, with two-thirds of Boomer women, for example, focused on financial security compared with just over half of Millennial women. These differences seem likely related to stage of life (Exhibit 4).

That said, it’s notable that across all age groups HNW women and men share similar life goals, most often improving their mental and physical well-being, strengthening their relationship with their families, increasing their wealth and creating a path to wealth for their children. They also face similar challenges to meeting those goals—most often an inability to predict the future, cited by half of men and 48% of women. This may in large part be because the women and men in the survey have many background similarities. Nearly equal percentages are married or living as married (82% of women and 85% of men, respectively) and are business owners or former business owners, business executives or professionals (64% and 66%).

Exhibit 4: The meaning of "wealth"

Percentage of each group who selected each choice (respondents could select up to three)

Equal shares of men and women, 63%, also expect to make more of an impact on the world with their wealth than prior generations. However, some distinct differences are apparent between female and male HNWIs about the direction of society and responsibility to contribute to it. For example, 61% of Boomer women agree society has become more inclusive, while 72% of younger women and 61% of men say the same.

72% of Millennial women think society has become more inclusive

Two-thirds of women believe they have more opportunity to tackle societal issues through impact investing, compared with 56% of men. (See the related article, “Women and Millennials reshaping investing and legacy in Asia,” for more on the changing role of impact investing among HNWIs.)

Among business owners, 72% of the women agree on the importance of their business making a positive charitable impact on the community and 71% a positive economic impact; the figures for men are 65% and 67%. (See the related article, “Female entrepreneurs drive social change in the UK,” for more on how female HNW business owners there are making a difference.)

63% of Millennial women expect the next generation will accumulate more wealth than they have

More Millennial women than Boomers expect the next generation will accumulate more wealth than they have (63% vs. 49%), with men overall falling in the middle, at 57%. Most women of all ages, 92%, express confidence that the next generation will have greater opportunities to own a business. However, although most HNWIs who own businesses would like to pass them on to their children, they all agree that they face a serious challenge in persuading their children to take over an existing family business instead of joining the corporate world or starting their own business.

Younger women giving back through investing, spending and more

Very few HNW men and women, just 4%, say they don’t have enough wealth to give to charity today. Among the majority who are giving, their major influences and preferences are similar but do vary among generations. And there’s even greater variety in how HNW individuals of different generations decide where to give and how they assess giving—all factors that relate to wealth and legacy planning as well as charitable giving itself. (See the related article, “The new Canadian legacy,” for more on how HNW Canadians are changing expectations about giving.)

Older women, for example, more often than Millennials, say charitable giving is not important to how they manage their wealth (22% vs. 7%) (Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 5: Connections between managing wealth and giving back

Percentage of each group who selected each choice (respondents could select up to three)

It’s also notable that women, somewhat more often than men, say that the ability to make the greatest impact—and particularly to measure that impact—influences their giving; 29% vs. 26% focus on the greatest impact, and 17% vs. 11% focus on measurement. Here, too, significant generational differences appear. Forty-four percent of HNW Boomer women say they do not assess the results, compared with 20% of Millennials and 27% of men. This may reflect a generational difference in how hands-on people prefer to be with their charitable giving. Older women also far less often rely on either traditional media or social media coverage/commentary to assess their giving than either younger women or men. However, formal and anecdotal feedback from the recipient and recognition from family are among the top indicators that all three groups—Boomer and Millennial women and men—use to assess the impact of their giving.

There are also generational differences in how they decide where to give. Millennials most often cite the ability to make the greatest impact (33%), while both men and Boomer women prioritize the relevance of the recipient to themselves. Tax benefits, however, appear far lower on Millennials’ list of priorities (19%) and are cited by more men and Boomer women (25% and 29%, respectively).

In terms of how they give, younger women more often (39%) align their investments with their giving goals—for example, through impact investing— than either older women (24%) or men (26%). Younger women also more often see impact investing as a form of giving, with 70% agreeing—compared with 47% of Boomer women and 52% of men.

(See the related article, “Creating social value now: How the idea of legacy in the U.S. is shifting,” for more on how HNW Americans align wealth management, giving and spending in support of social causes.)

A similar pattern shows up among female business owners. As a whole, they are more concerned than men about the non-financial impact of their wealth. They more often say it’s important to them to protect the livelihood of their employees and their families (74% vs. 67%) and that their business have a positive charitable impact on the communities in which it operates (72% vs. 65%).

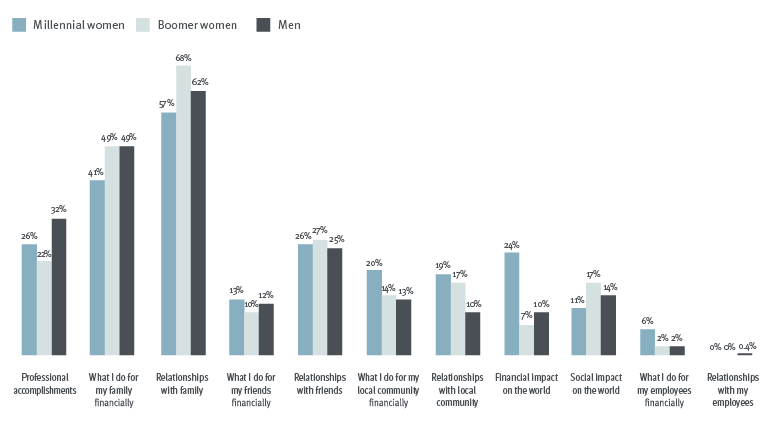

Women defining legacy with a social focus

If Millennials are an indicator of the future, then women’s increasing confidence in their ability to accumulate and preserve wealth is driving them in a more idealistic direction in which they prioritize charitable giving, align and integrate their legacy goals with their investments—for example, through impact investing—and make social obligations a larger focus of their legacy planning.

Millennial women agree they have greater opportunity to tackle social issues that personally interest them: 83% compared with 65% of older women and 66% of men. They more often than older women agree they have an obligation to transfer wealth to the next generation (65% vs. 55%). And majorities more often say they have a personal responsibility to use their wealth to benefit broader society (65% compared with 52% of older women) and that they have the opportunity to tackle societal issues specifically through investing (76% compared with 59%).

In that context, it’s hardly surprising that Millennials more often than Boomers distinguish their legacy goals from their parents’ goals: 81% of Millennial men and 69% of women say they define their legacy differently from their parents, compared with 58% of both Boomer men and women.

Another notable gender difference: Women far more often say societal causes have become more important than wealth accumulation in defining a legacy, with 62% of women agreeing, compared with 53% of men (Exhibit 6). This suggests that as women accumulate greater assets, they may shift more capital toward charitable giving and social projects, even at the cost of greater future wealth— though younger women’s engagement with impact investing may blunt any reduction in wealth accumulation.

Exhibit 6: Defining a legacy

Percentage of each group who selected each choice (respondents could select up to three)

When HNWIs plan their legacies, noticeable gender differences emerge. While women and men both, by large majorities, see wealth as the main enabler of their legacy, the number becomes overwhelming for Millennial men (91%)— far ahead of Millennial women (69%).

81% of women say it’s important for their wealth plans to align

The same holds true when asked if they have more opportunity to build a legacy than prior generations. Three-quarters of all women, younger and older, and Boomer men agree, but for Millennial men, the figure rises to 83%. Women also say, by a majority of more than two-thirds, that they are acting now with their legacy in mind. But here again, Millennial men posted an especially high figure of 79%. This may indicate that men are still more likely even than younger women to see their careers and wealth-building activities as creating a lasting legacy.

However, women increasingly are moving in their direction: 85% of Millennial women agree that it is important to lay a foundation to define their legacy for their family and future generations, compared with 74% of Boomer women. Yet, older and younger women agree that it’s important to align their wealth plans with the legacy they want to leave (83% and 85%, respectively). Overwhelmingly, they also agree that they are in control of their legacy (89% and 95%).

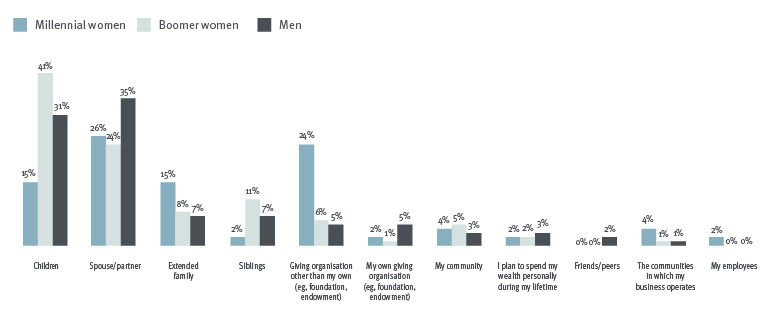

Finally, the survey detected some striking differences between how women and men plan to direct their legacies. Forty-one percent of Boomer women expect to give their wealth to their children—far more than Millennial women (15%)—while for all men, leaving wealth to their spouse and children are virtually tied (35% to spouses and 31% to children). Both women and men also expect to make more modest provisions for extended family. Older women expect to allocate very little to charitable targets such as the community in which they do business, foundations or endowments (their own or others’) or employees.

Exhibit 7: Who HNWIs plan to give their wealth to the most?

Percentage of each group who selected each choice (respondents could select one)

Conclusion

Women not only own and control greater wealth than ever before, they are also changing the direction of wealth management and the goals of wealth creation. HNW Millennial women, in particular, are taking a new direction. And, while many women still feel some of the familiar gender constraints, particularly as decision-makers, the survey suggests that the younger they are and the more wealth they accumulate, the less these apply. The picture that emerges is of high-net-worth women who routinely start and run businesses and who increasingly direct their own wealth-building. The more assets they accumulate, the more they direct their wealth and legacy planning themselves and the more their individual influence will be felt.

Written by

1. Boston Consulting Group, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2016/financial-institutions-consumer-insight-global-wealth-2016.aspx

2. Percentages do not add to 100% because of rounding.

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2018. All rights reserved.

Royal Bank of Canada, The Economist Intelligence Unit, and their respective marks and logos used herein, are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective companies. No part of this document may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means without written permission from The Economist Intelligence Unit.

Disclaimer

The material herein is for informational purposes only and is not directed at, nor intended for distribution to or use by, any person or entity in any country where such distribution or use would be contrary to law or regulation or which would subject Royal Bank of Canada or its subsidiaries or constituent business units (including RBC Wealth Management) to any licensing or registration requirement within such country.

This is not intended to be either a specific offer by any Royal Bank of Canada entity to sell or provide, or a specific invitation to apply for, any particular financial account, product or service. Royal Bank of Canada does not offer accounts, products or services in jurisdictions where it is not permitted to do so, and therefore the RBC Wealth Management business is not available in all countries or markets.

The information contained herein is general in nature and is not intended, and should not be construed, as professional advice or opinion provided to the user, nor as a recommendation of any particular approach. Nothing in this material constitutes legal, accounting or tax advice and you are advised to seek independent legal, tax and accounting advice prior to acting upon anything contained in this material. Interest rates, market conditions, tax and legal rules and other important factors which will be pertinent to your circumstances are subject to change. This material does not purport to be a complete statement of the approaches or steps that may be appropriate for the user, does not take into account the user’s specific investment objectives or risk tolerance and is not intended to be an invitation to effect a securities transaction or to otherwise participate in any investment service.

The text of this document was originally written in English. Translations to languages other than English are provided as a convenience to our users. Royal Bank of Canada disclaims any responsibility for translation inaccuracies. The information provided herein is on an as-is basis. Royal Bank of Canada disclaims any and all warranties of any kind concerning any information provided in this report.

While every effort has been taken to verify the accuracy of this information, The Economist Intelligence Unit Ltd. cannot accept any responsibility or liability for reliance by any person on this report or any of the information, opinions or conclusions set out in this report. The findings and views expressed in the report do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsor.