Highlights:

- Employment plunged an unprecedented 1.01 million in March

- The unemployment rate “only” increased to 7.8%, but the labour underutilization rate soared to a staggering 23%

- Layoffs heavily concentrated initially in lower-wage service-sector industries

- April labour market data will look (much) worse

- Government programs also unprecedented, and necessary to help households/businesses bridge the gap

Job losses on historical scale (and much more to come)

The 1 million drop in jobs in March reported this morning makes every other month-over-month change in the labour force survey data before look like a rounding error. The largest prior one-month declining dating back to 1976 was a 125 thousand decline. The job losses in one month were more than twice the total job losses in the 2008/09 global financial crisis. But the April decline could already be multiples of this March drop, given another almost 3 million people have reportedly applied for employment-loss benefits since the mid-March labour force survey reference period.

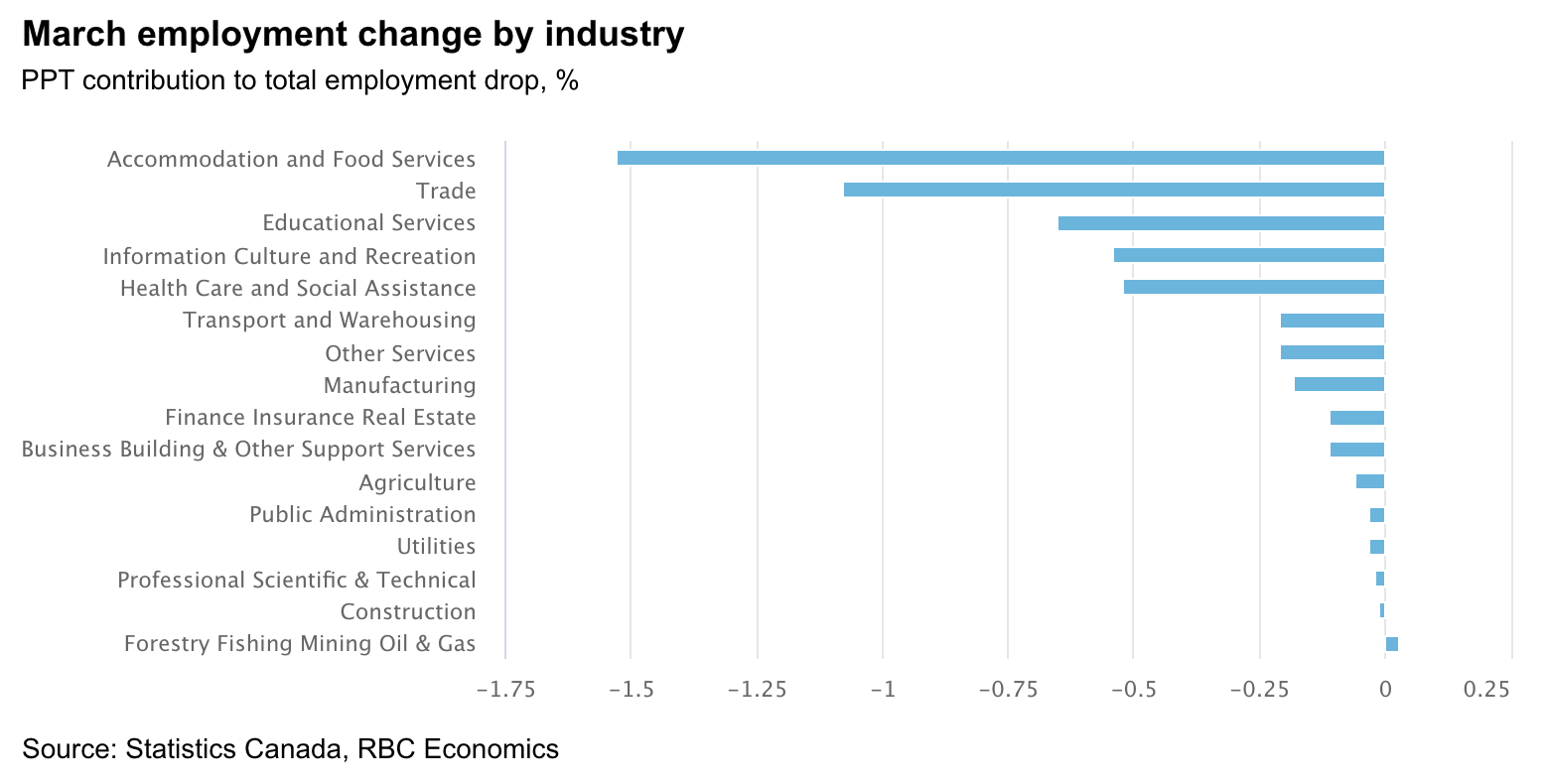

As expected, industries like accommodation & food services, cultural & recreation, and retail trade were among the most initially impacted by the implementation of social/physical distancing measures. Those three industries alone – all of which tend to be on the lower end of the average wage scale (and so including more vulnerable workers) – accounted for about 60% of total job losses. In total, service-sector employment declined by 964k, versus “just” a 47k drop in the goods sector. That is unusual. Normally the goods sector leads the economy into recession. This time, the downturn is being led by shutdowns in sectors that are typically more resilient than the goods sector to a downturn. Further goods-sector employment declines will come as stricter physical distancing measures have been implemented since the March survey week and weakness in the service-sector both in Canada and abroad spills over into demand for goods.

Unemployment rate increased less than feared, but that’s actually a bad thing

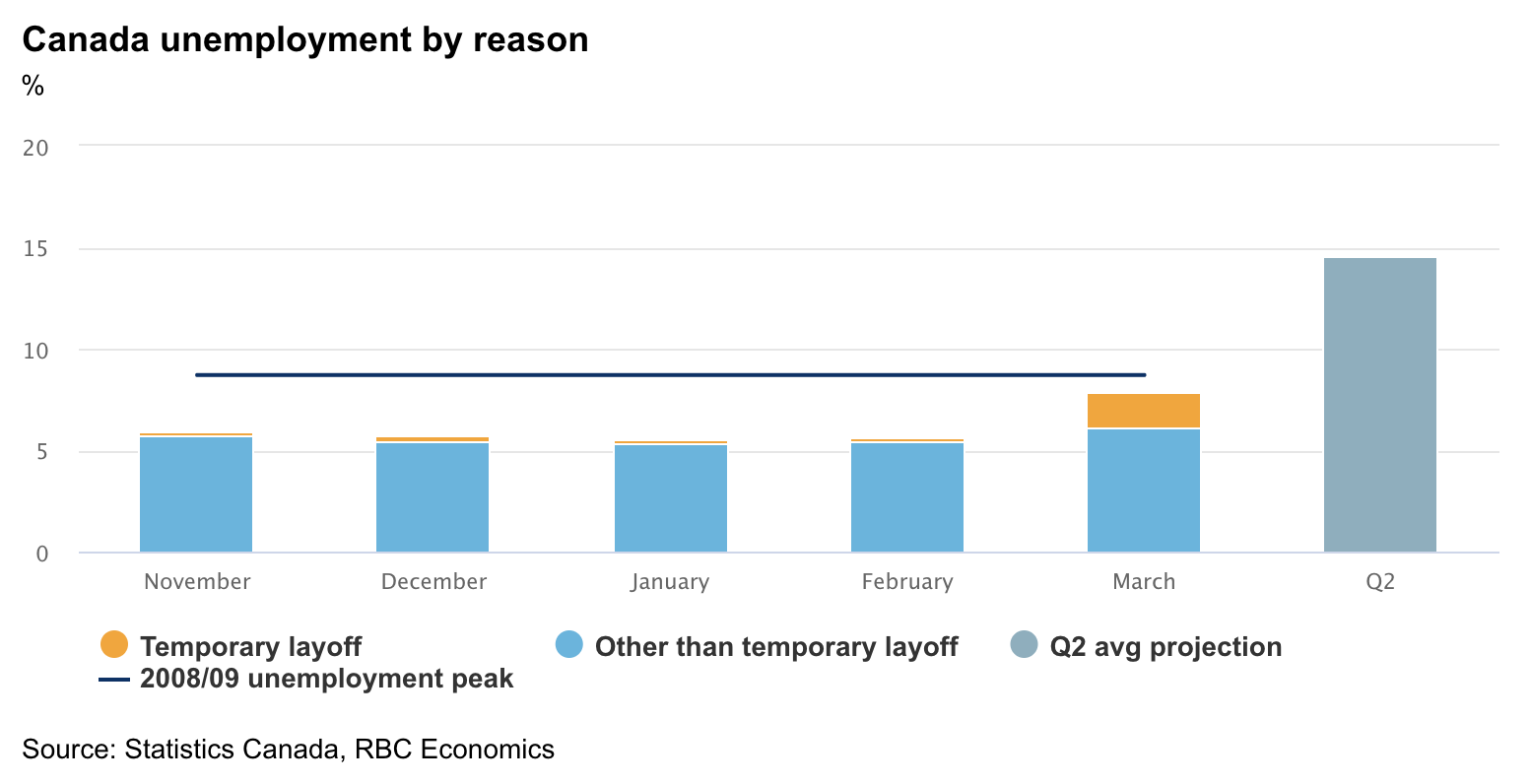

The increase in the unemployment rate to 7.8% (from 5.6% in February) was already double the largest one-month increase on record. But the scale of drop in employment in March normally would have been enough to push the unemployment rate much higher, to potentially above 10%. And the reason it didn’t jump that high is actually bad news. A smaller-than-expected share of initial job losses were temporary. Temporary layoffs are technically counted as “unemployment” but if a layoff is not temporary, then people that lose their jobs but haven’t been looking for work just drop out of the labour force altogether, and are not technically counted as unemployed. We would obviously rather see no unemployment increases, but since a large number of people are in fact losing their jobs, it would actually be a positive sign if a larger share of them were on temporary layoff rather than out of the labour force entirely. It would be a sign that the relationship between employers and employees is being maintained, and maintaining those relationships can speed the job market recovery once we come out the other end of this shock. The labour force participation rate also posted its largest one-month drop on record, falling 2 full percentage points to 63.5%.

Regionally increases in unemployment were concentrated in regions that were among the first to impose physical/social distancing measures, led by Quebec, BC, and Ontario. The unemployment rate in Newfoundland & Labrador actually declined in March, although even there that was despite a sizeable drop in employment being outpaced by a larger decline in the labour force.

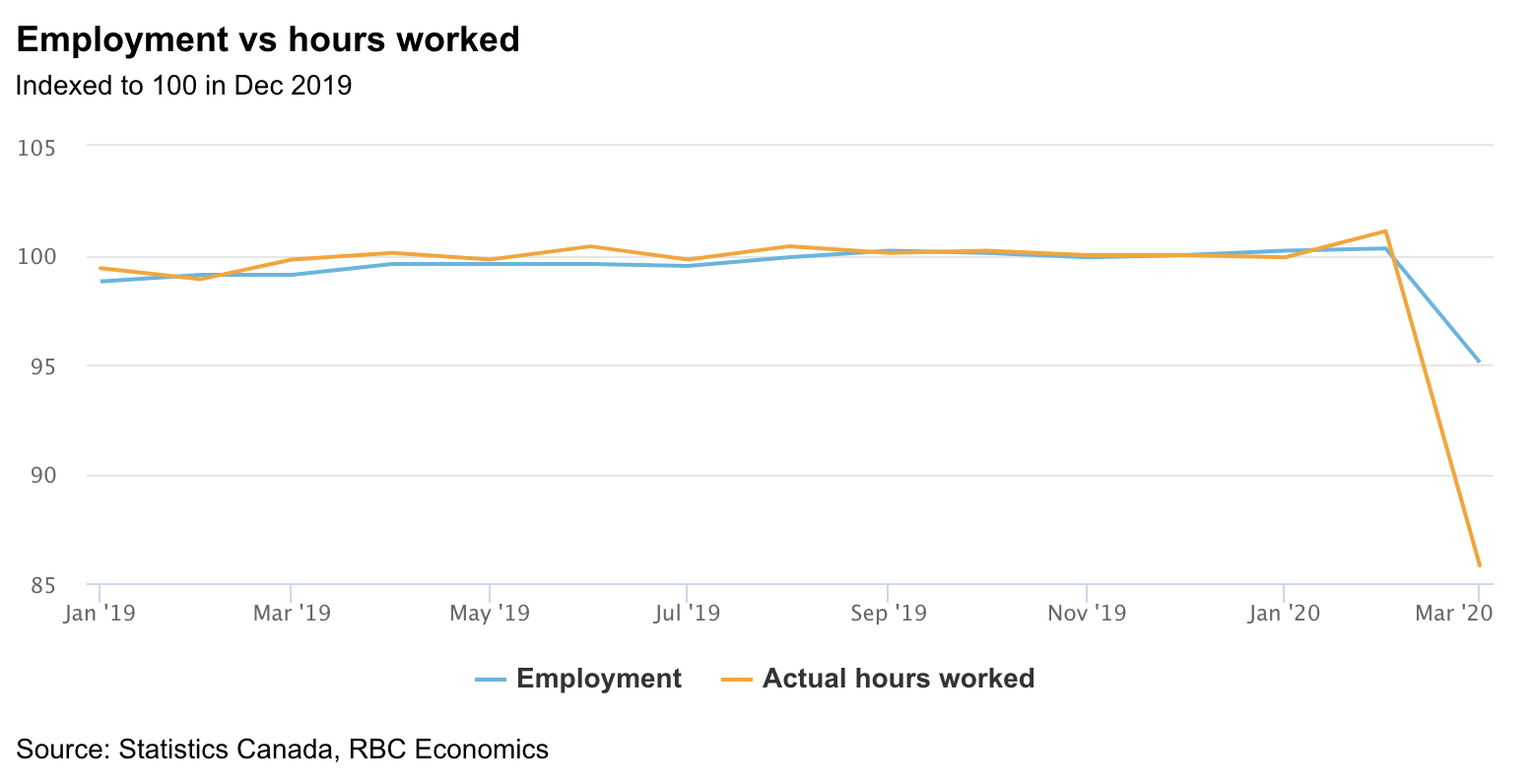

Those still working worked less hours – labour market underutilization staggering

And those still working worked substantially fewer hours. Actual hours worked declined by (an astounding) 15% in March versus a 5% decline in employment. That hours-worked decline was 5 times larger than the largest prior decline on record. Accounting for lower hours worked as well as those not working but not technically counted as unemployed, Statistics Canada estimated the “recent labour underutilization rate” at a staggering 23.0%. The unprecedented drop in hours worked clearly is consistent with what is widely expected to be an unprecedented drop in overall economic activity in Q2.

This will get worse, before it gets better

Our latest forecasts assume that the unemployment rate will average 14 ½% in the second quarter, double March’s 7.8% rate. That might be too high given the smaller-than-assumed increase in March, but only if a large share of layoffs continue to be non-temporary, and if workers drop out of the labour market rather than being technically counted as unemployed. The key to gauging the pace at which the economy can bounce back from the current downturn still depends on the extent to which employer-employee relationships can be maintained, and households and businesses can bridge the gap until current social distancing policies can be eased.

Government programs will help

An unprecedented labour market shock is also being met by an unprecedented increase in government support for households and businesses – both in Canada and abroad. The new Canadian Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), for example, represents a more generous income replacement at the bottom end of the wage scale – which is also where a large chunk of initial layoffs are occurring. Other programs like the pending Canadian Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS) program could push a significant chunk of the “unemployed” or “not in the labour force” population into “employed but working zero hours.” Of course, the number of actual hours worked won’t change just because of that change, but the program does provide a more generous (although still only partial) income offset for those losing their jobs further up the wage curve. These programs could distort some labour market statistics in the near-term, but provide important offsets to households to get through a period of unprecedented economic weakness.

This report was authored by Senior Economist, Nathan Janzen, and Economist, Claire Fan.

RBC Economics provides RBC and its clients with timely economic forecasts and analysis.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.