A (sometimes) regular compendium of my current thoughts on markets, the economy, and other random marginalia

I got my first AstraZeneca vaccine shot last week, and maybe it’s the just my new vaccine-derived superpowers talking but I instantly felt a lot more optimistic about the future. The past fourteen months has been an exercise in the abnormal. I haven’t been in my office, save two days, in that whole time. Like others, we are dealing with a daughter who bounces in-and-out of care, but unlike others Aveeve and I have multiple supports and flexible work schedules, besides. Restaurants closed again, throwing a mass of mainly younger, mainly less economically stable workers back into limbo, and threatening a number of business owners and good employers. COVID case numbers and hospitalizations have been rising alarmingly in Manitoba and across the country. But 47% of the country has had at least a first dose (40% in Manitoba), and supplies as coming in quickly now. And while I’ll happily line up for my second dose of whatever they want to put into my arm when it becomes available, I do hope that our leaders are paying attention to the need to vaccinate the world, not just the rich Western countries, so that we can avoid the mutations that we are seeing arise from areas of rampant, unchecked spread of the virus. Mask mandates and reduced store capacities may be around for a while longer, but I can now imagine a world where—bare faced and not smelling of hand sanitizer—I cram myself into an over-capacity venue for a live show, hugging friends, cheek-by-jowl with complete strangers.

Inflation musings

Markets may have ended the week on a positive note, but there was undoubtedly considerably more volatility than some of us have become accustomed to. If you’ve talked to me on the phone in the last four or five months, this is something you were probably prepared for. We’ve been saying for some time that while our expectations for 2021 were strong (re-opening? Yes, please), we expected to go through several stutters-start periods of skepticism. Of course, this is a common theme for recoveries. No one wants to believe they’re actually here to stay, so we start looking for all the things that could derail the recovery. And we’re not Pollyanna—there are definitely things out there that could cause us concern. We just haven’t seen any of those concerns being more significant than the potential for a more open economy. The cause-du-jour this week seems to be inflation.

Inflation is a term that everyone “knows,” but few can define. When you read a headline like, “U.S. CPI was up 4.2% year-over-year,” what that tells you is that this year it will cost 4.2% more for a defined basket of goods as it would have last year (the Consumer Price Index). Inflation is normal. In fact, we have been living in a largely under-inflated world for a while now, and at the time, everyone worried about that.

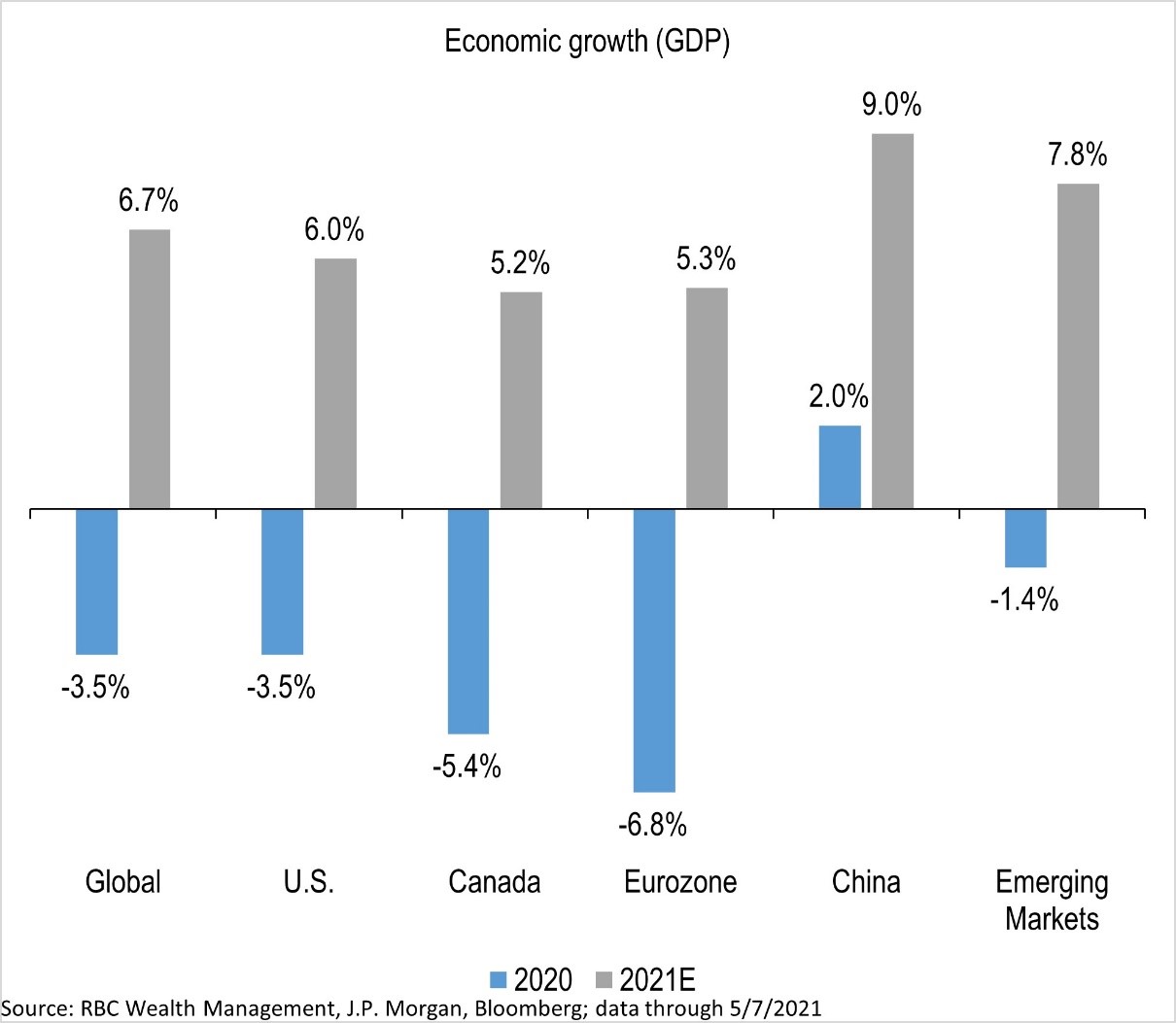

What this misses, of course, is context. 4.2% was well ahead of estimates of what U.S. inflation would be but remember what was going on a year ago—economies around the world had shuttered, stores had sales for everything but toilet paper and baking yeast, and we were finding out what “curbside pickup” was all about. Working off a distorted starting place is called a “base effect,” and we’ll be dealing with the pandemic’s base effects for a little while still. Add onto that some particular supply chain constraints on significant parts of the consumer goods basket—wood, gas, and microchips—and you have the recipe for a bit of extra oomph under the price of things. Then further add to that that global growth is recovering.

Will inflation be here to stay? It’s hard to say. As we all know, prices tend to be sticky for many things we buy, especially durable goods. No doubt, once increased raw material costs are successfully passed through to consumers, many manufacturers will opt for healthier margins in future sales over reducing prices if consumers accept the higher prices. Supply chain challenges will fade over the next year as we bring more global manufacturing online, and investment in robotics, automation, and other efficiencies will have a deflationary effect. And then there’s the commodities, the rawest of material inputs, which look to be at the start of a significant super-cycle. It remains to be seen what the net effect of all of this will be, but runaway 80’s-inspired inflation doesn’t seem to have a particularly good thesis behind it, and some circuit-breakers would need to be tripped first.

What does this all mean for investors? Well, inflation of any kind has winners and losers. Banks and insurance companies love inflation because these are both “spread” businesses, which make the bulk of their money on the difference between borrowing and lending rates. It’s a lot easier to make more money when interest rates rise above the near-zero that they have been for more than a decade now. Another obvious winner is anyone who has a lot of assets already. Think businesses with assets in the kinds of things that are getting progressively more expensive every year for your competitors to build:

- huge or particularly high-tech manufacturing plants;

- infrastructure projects like ports and rails, as well as transportation networks;

- fibre and 5G telecommunications networks;

- and yes, even office towers, hotels, and [shudder] cruise ships.

Other businesses that benefit in an inflationary environment are the second-order businesses which help allay some of the costs listed above:

- automation and robotics, as well as semiconductors and data centres;

- resource efficiency (think technologies that reduce material inputs);

- supply-chain efficiencies;

- anything that can reduce labour costs or increase labour efficiencies (like CRM companies);

- dominant retailers are helped because their supply chains tend to be more flexible.

Businesses that can deliver on the above would be expected to do well against their competitors, and sectors related to the above themes would be expected to do well. And it would certainly seem that businesses have gotten the message. They are currently spending large amounts on software and tech, while leaving off spending on structures.

There are business models that don’t work so well or that implode in an inflationary world. One of the worst-hit is anything with a subscription service and elastic demand. If average revenue per customer doesn’t change, but costs rise, or customer acquisition slows or reverses, margins are squeezed and earnings fall off a cliff. Many of these businesses have low margins to begin with (because they tend to be asset-light and therefore have many competitors), so there already isn’t a lot of room for error.

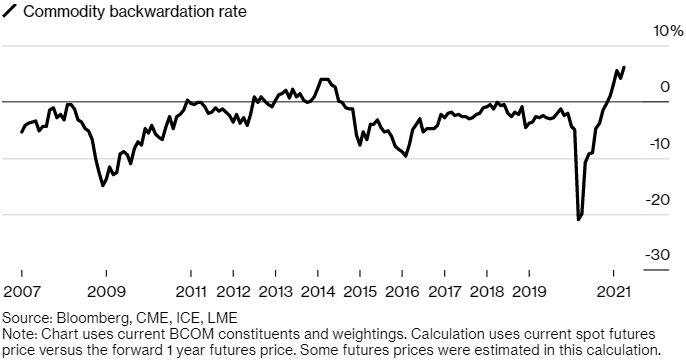

Outside of the stock world, hard assets like real estate, commodities (particularly gold, copper, and oil), and—who knows—maybe even cryptocurrencies are helped because they inflate with everything else. Backwardation—the premium for delivery of a commodity today versus delivery in the future—is as high as it’s been since 2007. It’s called ‘backwardation’ because it’s usually more expensive to buy something for future delivery. The carrying cost of holding an inventory usually comes into play. Backwardation happens when there is urgent demand for a commodity today.

The other two major asset classes—cash and bonds—are the real losers in an inflationary world. Because the cost of goods is going up, the same $1000 sitting in a bank account buys progressively less and less “stuff.” Cash is, by its nature, a non-productive asset, and if it’s not invested in something, it will always lose value over time. The same can be said for bonds, which provide an interest payment, but the maturity value will be less than the principal was when it was invested. Bonds already owned prior to a bout of inflation are double losers because the coupon payments were set when interest rates were lower, and each coupon buys progressively less than the one before it. At least new bond buyers can hope that the interest rate is set high enough to compensate for the loss of buying power in the future.

That isn’t to say that cash and bonds don’t have a place in a properly diversified portfolio. As recent volatility has demonstrated, sometimes “cash is king” is a valuable aphorism, especially when you need money in the midst of a market hiccup. And if that cash need is probably or potential, or if it’s further out in the future, having something that pays you some interest, whatever that interest is, is better than cash paying no interest. Part of the reason we focus so much time with our clients on figuring out what their needs and goals are is to make sure that funds are available for them—safely—when they need them. It also allows us to put the rest of their savings to more productive uses. Because the best hedge against inflation out there is to own growing companies wherever you can find them, for as long as possible. But you can’t do that if you don’t know when you might need those savings for something more fun.

Sell in May and go away? Probably not.

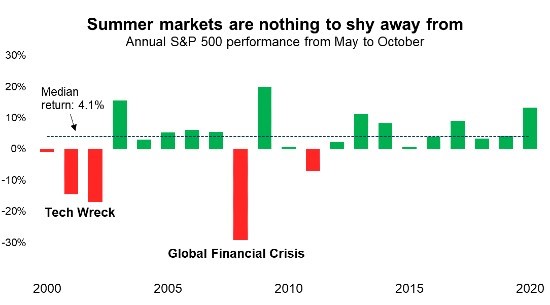

There is an old market saying that one should “sell in May and go away.” The thinking goes that investors would be well-served by turning their investments into cash and taking the May-October period off, buying back in in the fall. Ignoring the fact that this is half of the year, and further leaving aside all of the dividend one would be forgoing to enact this plan, it turns out it’s just not a very successful strategy, as this table from RBC Capital Markets shows:

Analysis of the “damage” from the May-October period can be pretty much completely attributed to the Tech Wreck and the Global Financial crisis. The U.S. stock market was positive 76% of the time from May to October and returned an average of 4.6% over that period. Leaving that on the table doesn’t seem like the most effective of ideas.

Marginalia from around the web

- Burn All the Leggings (Amanda Mull, The Atlantic). I am not a fan of the current trend of referring to anything not sweatpants as “hard pants,” but this piece does raise an interesting question: what will fashion look like, and who will be primed to take advantage of any shifts. The article contains some interesting parallels to historical pandemics and other global events for clues.

- The impact of inheritance (Meredith Haggerty, Vox). “Inheritance is a tricky thing to talk about, a subject that wraps up money, family, and death in one impossible package. For those who receive it, or stand to, it’s wealth that comes at a terrible moment; a boon and bureaucratic puzzle; and a reminder of someone you lost.” Next week, Monday to Wednesday I will be “out of the office” (which, these days, just means sitting in the same place I have for the past months) participating in Session #4 of my Financial Enterprise Advisor designation course. This article on the coming massive wealth transfer, and its differing effects on wealthy- and middle-class- families, struck a nerve and contains some useful insights.

- Quantum Mechanics, the Chinese Room Experiment and the Limits of Understanding (John Horgan, Scientific American). This is not a physics article. It is a fascinating reflection on cognition, and how we know anything at all, or whether we even do. How, after all, do I know that what I respond when asked a question has anything to do with anything other than a complicated algorithm running behind the scenes of my consciousness?

- Everything Is Becoming Paywalled Content—Even You (Jason Parham, Wired). I don’t know that I buy everything in this article—it suggest a somewhat dystopian world where incidental community is impossible, personal connections just for the sake of friendship aren’t valuable, and the commodification of self becomes supreme. But the general theme of marching towards a pay-as-you-go, subscription everything world is certainly something I see more and more of. The push (recently accelerated by Apple’s new privacy features) to kill the “your data is the product” internet will undoubtably accelerate some of the subscription- and paywall- centered business models.

- Podcast: How the World’s Great Vaccination Hope Crashed (What’s Next: TBD, Slate). The Serum Institute in India was supposed to be the answer for the Global South’s vaccine needs. But despite all best hopes, nothing has worked out, and the country responsible for making vaccines for the world can’t even get vaccines out to its backyard.

- Podcast: Brown Box (Radiolab, WNYC). This is a refresh of a story that was first published in 2014. The story itself was fascinating, and expose on 3PL companies (think, Amazon warehouses) reported by incredibly accomplished investigative reporter Gabriel Mac. Of additional interest, the story was first published when Gabriel was just starting his gender transition, so it was originally presented under the byline “Mac McClelland.” There is an insightful addendum to the piece at the end, where the hosts discuss with Gabriel what it’s like to produce so much award-winning journalism under a different persona.

- Podcast: Hot Lotto (Criminal, Radiotopia). The host of Criminal, Phoebe Judge, has one of the best voices in podcasting (she has another podcast, This is Love, which is also a favourite of mine). This is an entertaining heist story of a multi-million dollar lotto ticket winner, and the web of deceit surrounding the mystery of the man who walked away from his winnings.

RBC Disruptors Podcast

Speaking of podcasts, we have started hosting episodes of John Stackhouse’s RBC “Disruptors” podcast on our blog. John is a Senior Vice President, Office of the CEO, and RBC’s current “innovation guru,” providing us with his insights on the future of work, markets, and the society that drives both. All the episodes can be found here: McLaughlin Capital Management - Podcasts (Disruptors). This week, John touched on a topic that I have been thinking about myself recently since finishing an excellent book, Futureproof: 9 Rules for Humans in the Age of Automation, by Kevin Roose—the idea that as automation takes a significant part of the rote labour off all of our desks, it will push the need for all of us to provide more value add than just “doing the work” in our jobs and our lives, and how this will affect professionals even more than it will factory workers.

Shameless Leila photo

As the world gets shakily back to normal, and as the weather warms up, just remember that life is really all about horridly constructed / unrecognizable and kind of creepy Spongebob Squarepants popsicles. I mean, we can’t eat well all the time can we?