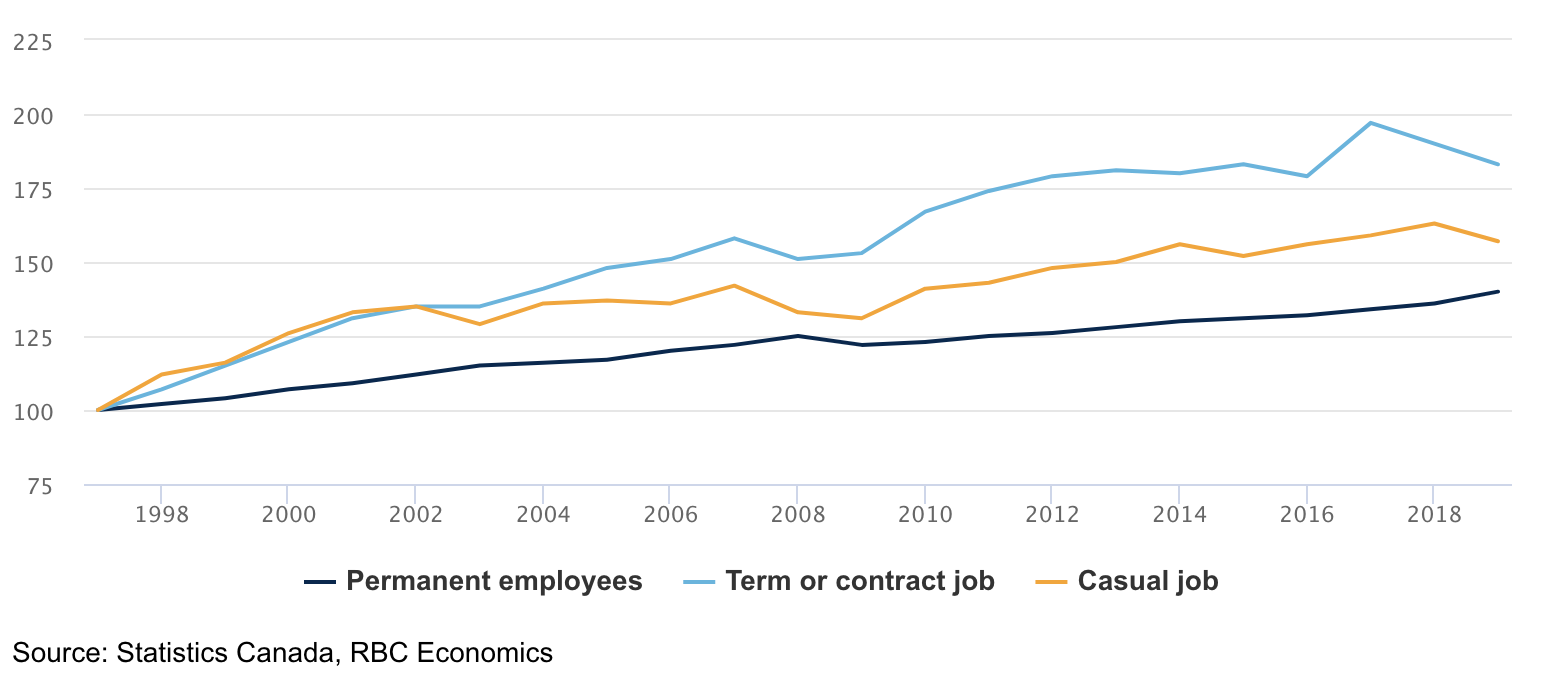

While office workers with the ability to work remotely face less disruption, services-sector employees required to come into direct contact with others face layoffs of indefinite duration. The blow is all the sharper because the share of Canadians working in services industries has been rising over time; four in five Canadians now work in the services sector. What’s more, there’s been a notable shift towards non-permanent work due to the rise of the so-called gig economy.

Highlights:

- COVID-19 will hit Canadian labour markets hard, and fast—particularly the 2 million-plus Canadians without permanent work arrangements

- 93% of casual employees and 85% of temporary contractors work in the services sector

- Nearly half of casual and contract workers are in sectors heavily impacted by COVID-19: education, accommodation and food services, wholesale and retail trade, and information, culture and recreation

- Around 800,000 casual and temporary-contract workers are prime-aged workers

- In April, the number of young people (mostly students) seeking seasonal or temporary-contract jobs will more than double—and their employment opportunities have diminished significantly

COVID-19 struck fast

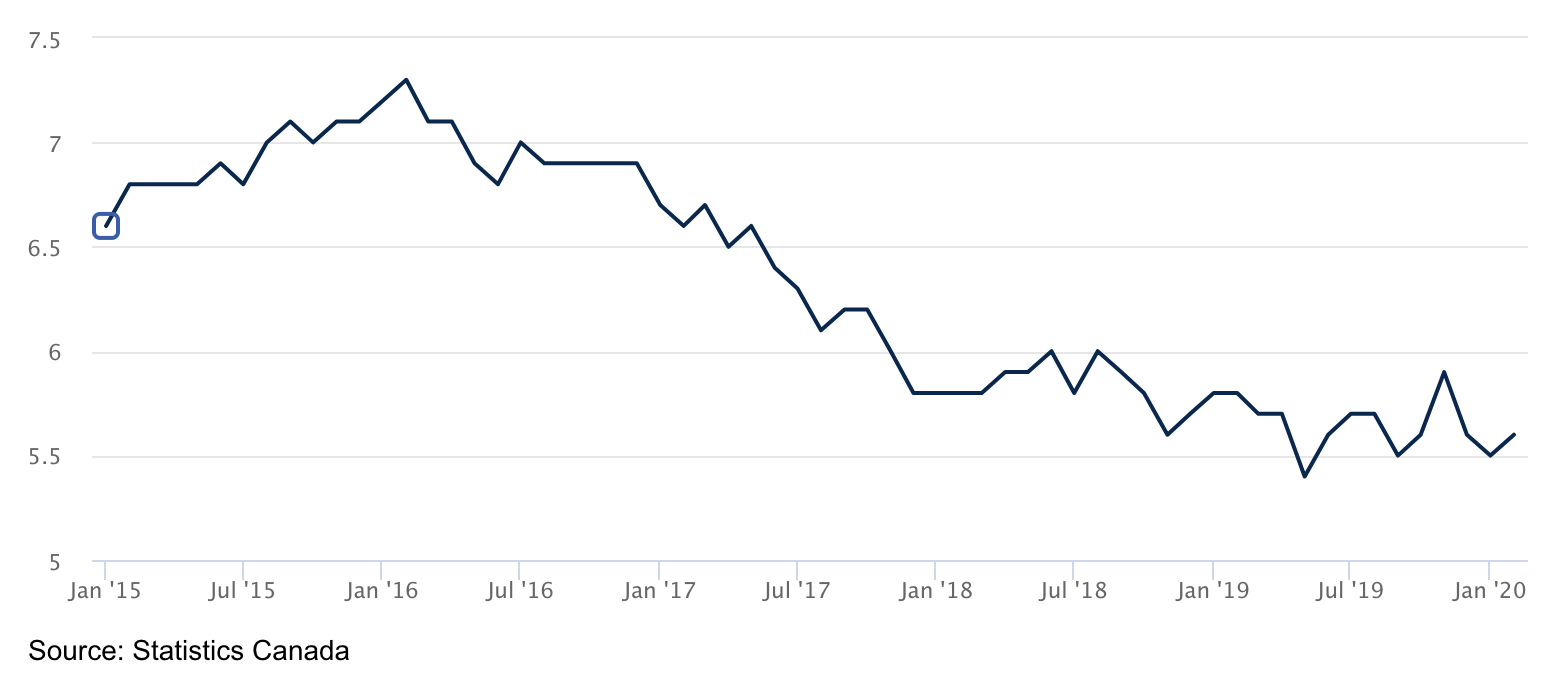

Heading into 2020, the Canadian labour market was very strong. Unemployment was at four-decade lows after hitting a recent high of 7.3% in early 2016. Even at the end of February, there was very little indication of the negative economic shock to come.

Canada's labour market entered the new decade with strength

Unemployment rate (%)

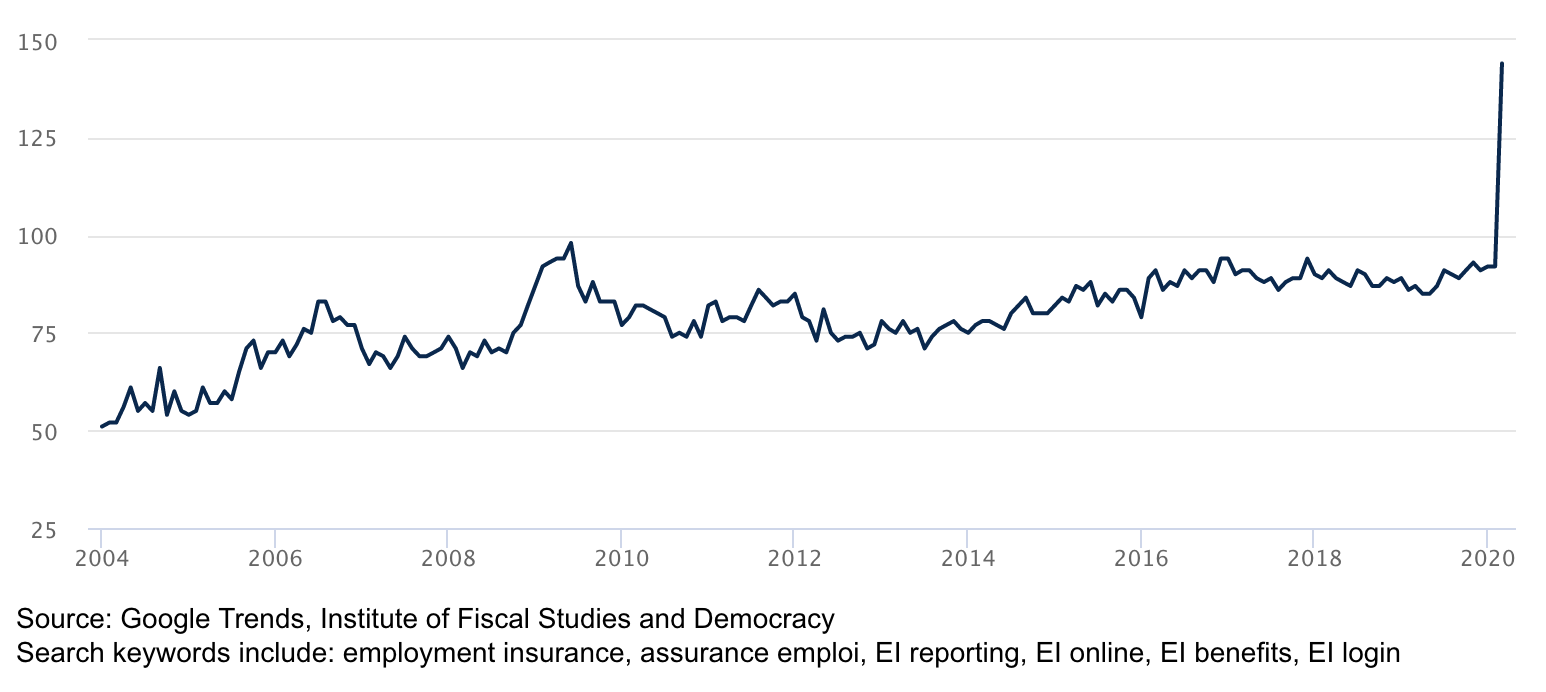

Since then, virus-curbing measures by the federal and provincial governments, as well as private sector companies have been felt across broad swaths of the labour market. While official data is still unavailable, Google searches for terms related to employment insurance have surged.

Searches for keywords associated with EI have skyrocketed

Google Trends index (sa)

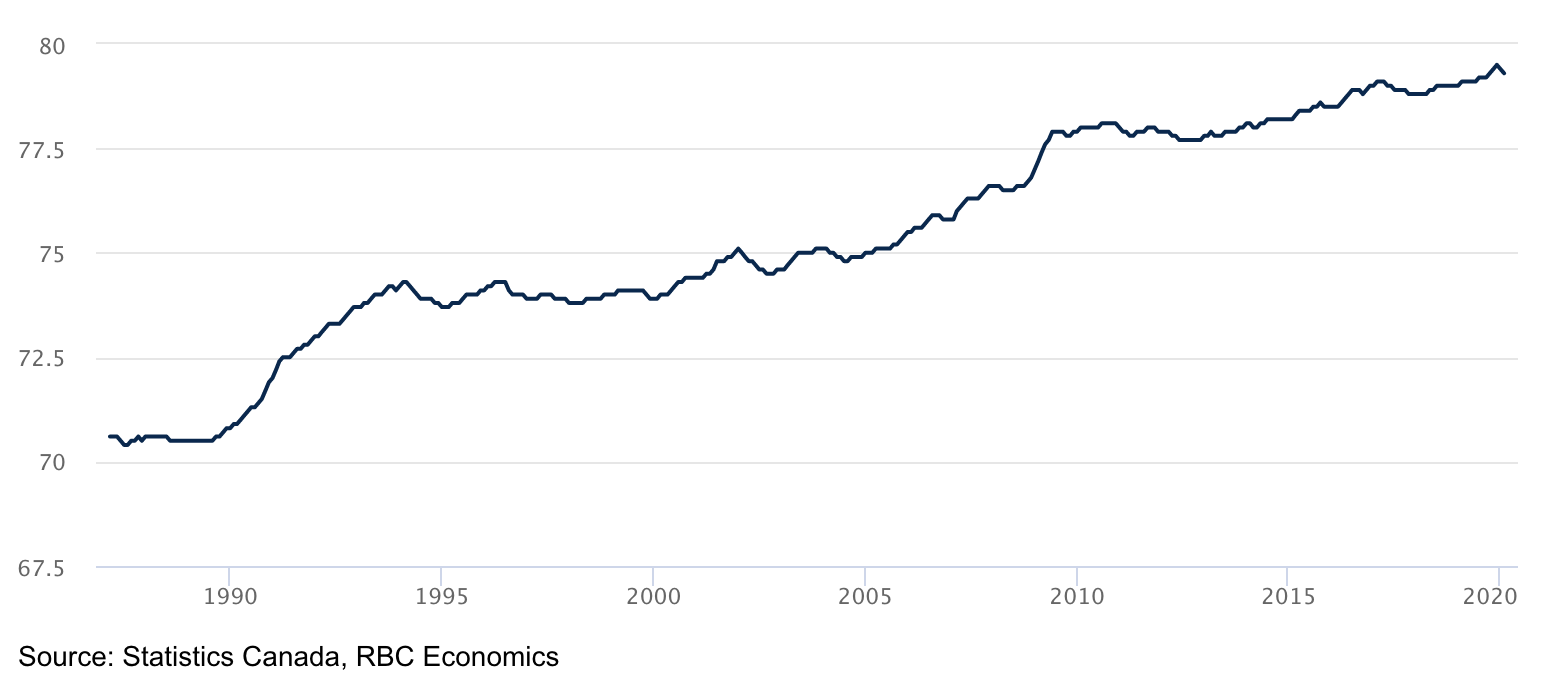

Canada’s services-based economy is particularly susceptible

We’ve identified two trends that set up the COVID-19 shock to exert even greater downward pressure on the labour market: the large increase in the employment of casual and temporary contract employees relative to permanent staff, and the large shift out of goods sector employment into services.

Service sector share of employment has been steady ascent

Percentage (%) of total employment that is in sector (rolling 3-month average)

Of Canada’s 2 million casual/temporary workers (which make up 12% of all employees), 93% of casual employees and 85% of those on temporary contracts are in the services sector. While the shock to oil, and the likely reduction of demand from abroad, will undoubtedly hurt the goods sector going forward, widespread “social distancing” is shaping up to be a demand shock of previously unseen magnitude for the services sector. Support staff for professional services will likely also see large reductions in demand.

Canada has increasingly shifted to less permanent work

Employment index (1997 =100)

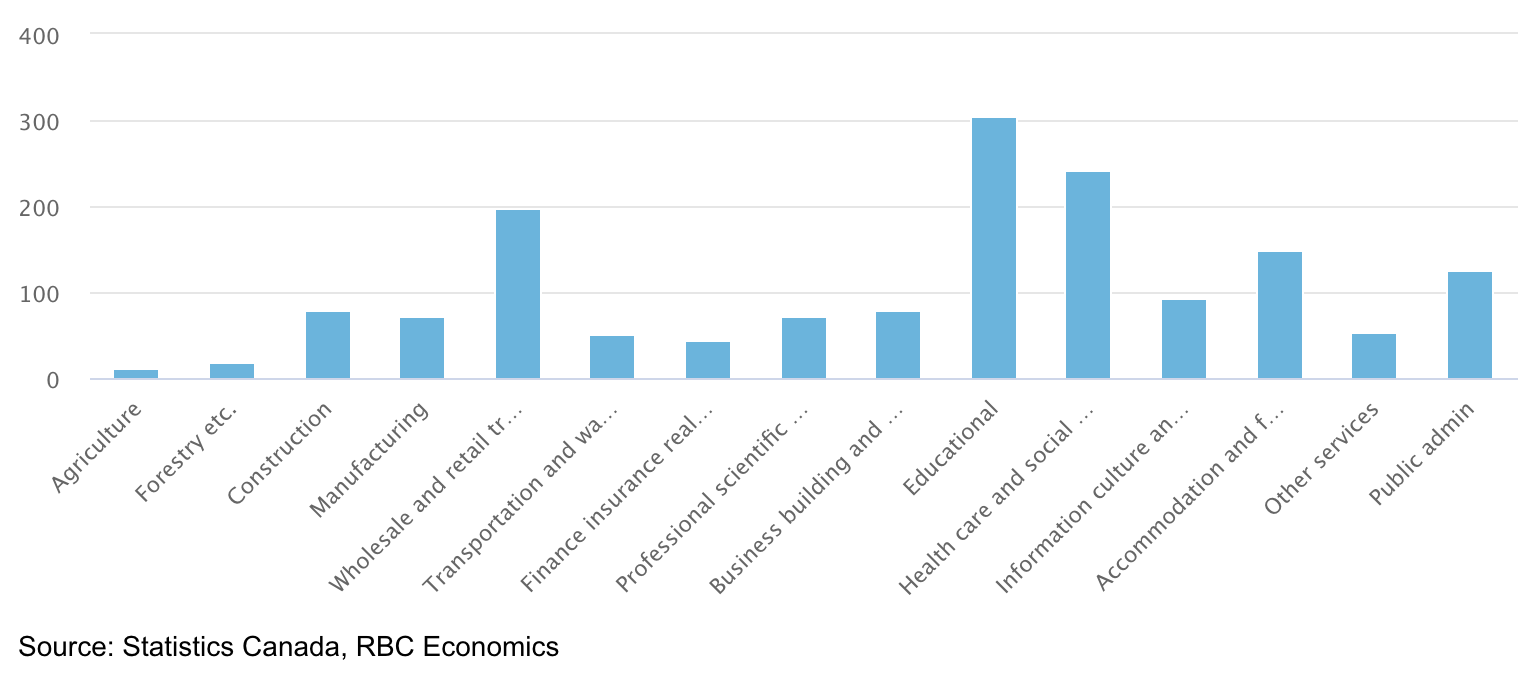

Casual and contract workers largely work in education, health care, accommodation and food services, and wholesale/retail trade. While health care is unlikely to see significant declines in employment, skills requirements will make it difficult for workers in other sectors to move into health care quickly.

In education, accommodation and food services, and information, cultural and recreation, there are over 700,000 workers without permanent positions. And given that these workers typically earn less than similar permanent workers, and are unlikely to receive paid time off, a long break of possibly months sets the stage for a period of financial stress.

Casual and temporary contract workers are concentrated only in a few sectors

Thousands of workers

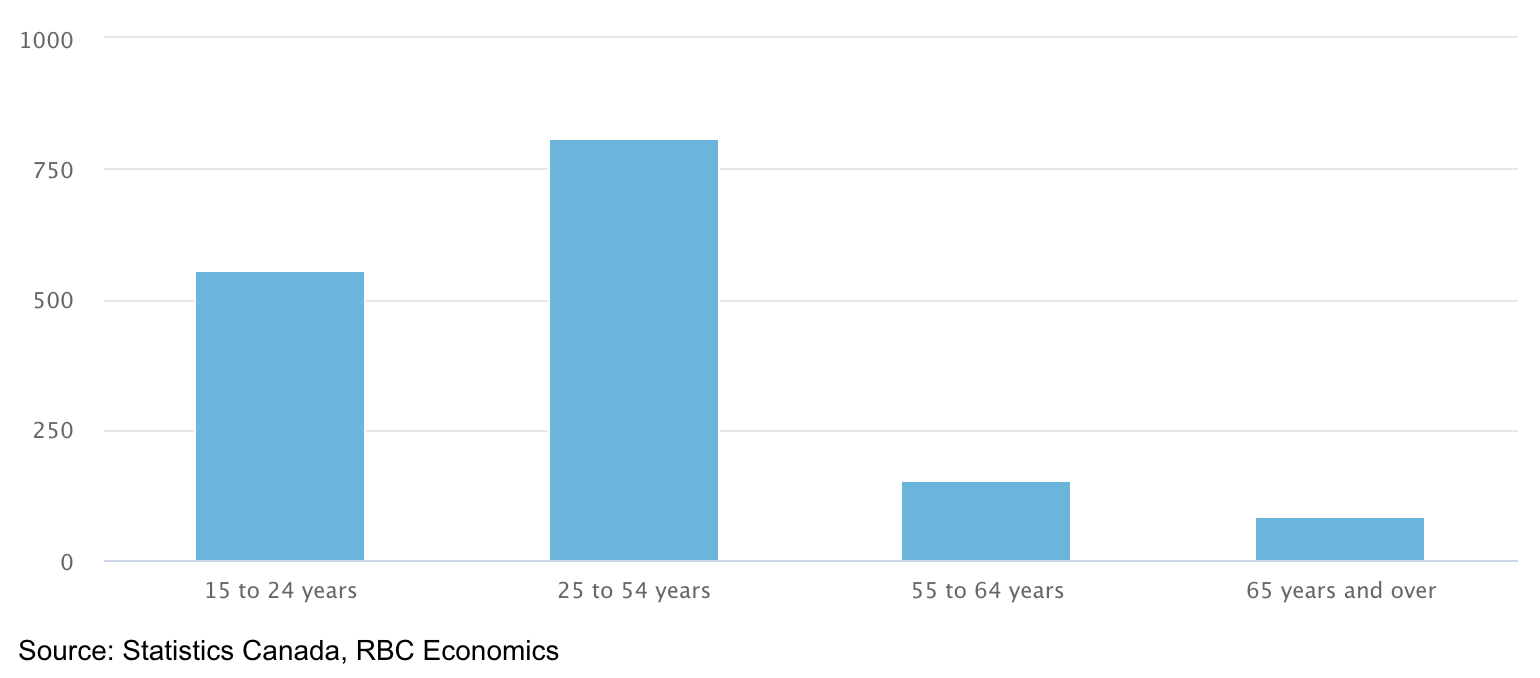

Casual workers and those on temporary contracts tend to skew young. Nonetheless, nearly 800,000 Canadians with such work arrangements are in the 25 to 54 year age range.

Over 800 thousand prime-aged workers doing casual or temporary contract work

Thousands of workers, 2019 data

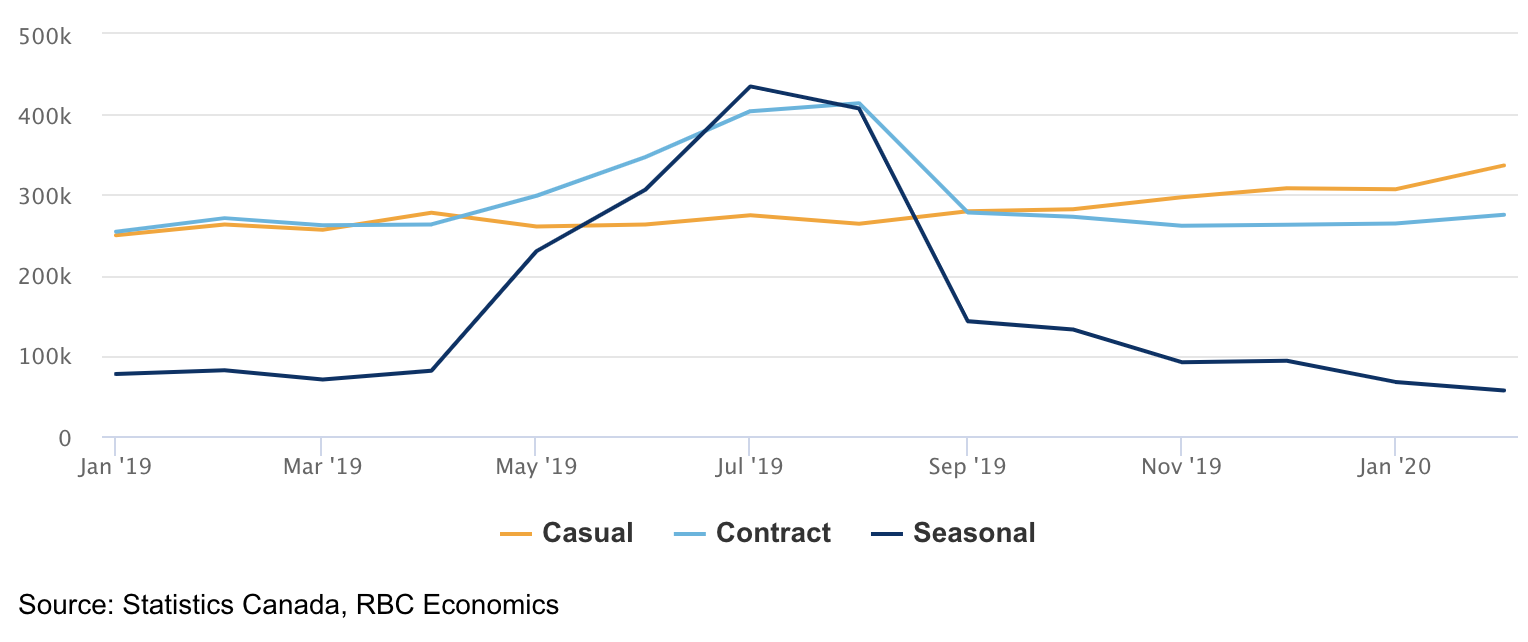

We are approaching summer job season

Finally, with the timing of this crisis in the final months of the school semester, many summer jobs for students are at risk. Beginning in April, 15 to 24 year olds begin to take up employment in large numbers. Nearly 1 million Canadians in this age range worked in a seasonal or contract position in 2019. With many firms instituting work from home policies, it is unclear what will happen to co-op and other internship positions. And for those that usually earn their income in bars, restaurants, or in other service positions, the disappearance of these jobs can put their yearly income at risk, making tuition and other expenses during the rest of the year unaffordable.

Just under one million Canadians aged 15 to 24 getting ready to start their summer jobs

Thousands of workers

Existing Government support likely won’t be enough

In response to COVID-19, the Government of Canada announced a stimulus package which includes some measures that will help soften the blow for those in unstable work. Enhanced Canada Child Benefit and GST rebate cheques will help lower income families and those with children struggling to make ends meet, but likely won’t be sufficient to buffer income losses. Workers affected directly by the virus (i.e. ill or caring for family who are, or children off school) will qualify for income support regardless of EI status. The benefit is long-lived enough to help buffer temporary shocks, at 15 weeks, but longer unemployment bouts will rely on traditional (and often insufficient) EI.

Workers who lose their jobs but don’t qualify for EI (many part-time and casual workers) will also see some support, but details on this new program are light, and it’s not yet clear how this helps if conditions continue on into the late spring or even summer. It will be important for the federal government to address lost wages for those that are unable to work in the future because of shutdowns caused by COVID-19, but do not have employment now.

And as we documented recently in our report The Recession Roadblock, those university students approaching graduation this April may find their initial job search stunted. Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) has projected that in 2020 nearly 500,000 new graduates (of all schooling levels) will be looking for jobs. The unprecedented shift towards working from home may cause some firms to worry just how they would be able to provide training to these fresh graduates, above and beyond the reluctance to hire in the midst of a major economic shock. Existing government support has focused on recent grads, with a principal and interest moratorium on government student loans. This won’t help new grads nearly as much, and governments will need to find ways to help this cohort transition into the workforce more smoothly to avoid lower future earnings.

Andrew Agopsowicz is a Senior Economist working in both the Economics and Thought Leadership groups. He studies the labour market – largely focusing on the future of work, demographic change, diversity, and human capital. Before joining RBC, Andrew was a Senior Economist at the Bank of Canada.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.