The S&P 500 has always been viewed as a balanced cross-section of the U.S. economy. Over time, it has slowly transformed into a tech- and AI-dominated index.

As 2026 begins with markets near record highs, this fact should be top of mind for investors.

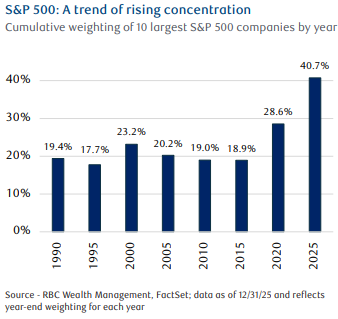

From 1990 to the AI era In 1990, the S&P 500 looked like a far more representative cross-section of the U.S. economy. The 10 largest companies by market cap (including IBM, Exxon, General Electric, and Philip Morris) made up roughly 19 % of the index. Leadership was spread across multiple sectors, and no single industry dominated overall returns.

That began to change during the late-1990s technology boom.

By the end of 2000, the top 10 accounted for roughly 23 % of the index, driven by the rise of companies such as Cisco, Microsoft, and Intel. The subsequent unwind was sharp, and the early-2000s reset led to a period where concentration declined as energy and consumer stocks regained prominence.

By the end of 2000, the top 10 accounted for roughly 23 % of the index, driven by the rise of companies such as Cisco, Microsoft, and Intel. The subsequent unwind was sharp, and the early-2000s reset led to a period where concentration declined as energy and consumer stocks regained prominence.

A more durable shift began after the 2008 financial crisis with the rise of the platform economy, (software, cloud computing, and digital), which created business models capable of scaling with minimal marginal cost.

Even then, concentration remained relatively modest for a time.

By the end of 2015, the top 10 stocks accounted for about 19 % of the S&P 500’s weight and roughly 19 % of total index earnings, suggesting that market value and fundamentals were broadly aligned.

That balance has changed meaningfully over the past decade.

By the end of 2025, the 10 largest companies accounted for nearly 41 % of the S&P 500’s total weight, more than doubling in just 10 years.

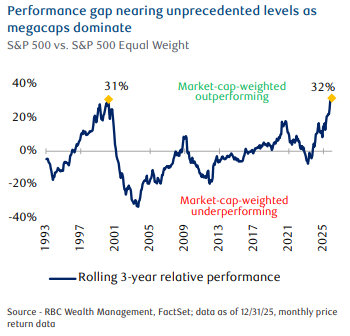

The effects are most visible when comparing the market-cap-weighted S&P 500 to the S&P 500 Equal Weight Index, which assigns each constituent an equal allocation.

From 2003 through 2022, the equal-weighted index actually outperformed the cap-weighted index by roughly 1.5 % per year, reflecting size effects and periodic mean reversion among large-cap leaders.

However, this relationship has broken down meaningfully since the beginning of 2023.

Over the past three years the market-cap-weighted S&P 500 has outperformed its equal-weighted counterpart by roughly 32 %. This represents one of the largest three-year relative outperformances on record, exceeding the approximately 31 % outperformance observed in the late 1990s and early 2000s in the run-up to the tech bubble.

The outperformance has coincided with a dramatic widening of the valuation gap, as the market-cap-weighted S&P 500 now trades at a nearly 30 % premium to its equal-weighted counterpart, up from approximately 13 % just prior to the pandemic.

This reflects how index concentration has risen significantly faster than earnings contribution.

In 2025, the top 10 stocks represented roughly 41 % of the index’s total weight but were expected to generate only about 32 % of its earnings. That gap has widened meaningfully since 2015, when weight and earnings contribution were more closely aligned.

While the largest companies remain highly profitable, market value concentration has increasingly run ahead of fundamental profitability.

It is important to acknowledge that today’s concentration is not speculative. Unlike prior market peaks, the largest constituents of the S&P 500 are highly profitable businesses with strong balance sheets, durable competitive advantages, and substantial free cash flow generation.

It is important to acknowledge that today’s concentration is not speculative. Unlike prior market peaks, the largest constituents of the S&P 500 are highly profitable businesses with strong balance sheets, durable competitive advantages, and substantial free cash flow generation.

Many are returning capital to shareholders while continuing to invest heavily in growth, particularly in AI-related products and infrastructure.

Elevated concentration alone is not sufficient evidence of a bubble.

The current structure introduces several risks worth monitoring.

- Shock Risk: Today is materially higher. In 1990, an earnings miss at a top holding would have had a limited index-level impact. Today, with NVIDIA alone representing nearly 8 % of the index, a single company can meaningfully influence index returns, affecting portfolios that assume broad diversification.

- The Passive Concentration Trap: Many investors believe an S&P 500 fund offers wide diversification. But, more than $40 of every $100 invested flows into just 10 companies, increasing their weights and reinforcing performance leadership regardless of fundamentals.

- Correlation Risk Tied To AI Exposure: Unlike past periods when the top 10 spanned unrelated industries, today’s leaders are closely linked by a common theme—AI. That effectively turns the index into a directional bet on AI adoption and monetization. If expectations slip or timelines extend, there are fewer offsetting exposures within the index to absorb the impact.

What does this mean for investors?

The “Great Narrowing” of the S&P 500 reflects a structural shift, where a handful of technology and AI-driven giants now dominate the index’s composition, performance, and risk profile.

While current leaders boast robust fundamentals, strong profitability and competitive advantages, , the concentration of market value in a narrow cohort introduces new risk.

The disconnect between weight and earnings contribution, outsized influence of individual stocks, and passive inflows amplifying this dynamic serve to remind us that what appears as broad diversification increasingly functions as a concentrated allocation.

For investors, this evolution requires a recalibration of assumptions. The S&P 500 has been a resilient benchmark, but its top-heavy structure warrants scrutiny.

Understanding embedded risks, from volatility to thematic correlation, is more essential than ever.

If you have any questions or comments, please do not hesitate to let me know.