As tariff policy heats up again in Washington, investors, businesses, and consumers are bracing for impact. While headlines often focus on the politics, the real story lies in how tariffs make their way through the economy—and what they could mean for jobs, inflation, and growth.

At RBC Economics, we’ve developed a transmission framework to help trace the effects of tariffs across different parts of the economy. With the average effective U.S. tariff rate now sitting at 13.8%, and higher rates on goods like metals and autos, we believe the U.S. is heading into what we call a “stagflation-lite” environment—where inflation stays elevated even as the labor market starts to soften.

However, the pace and severity of these effects will depend on two big variables:

1. How much inventory has already been built up ahead of tariff implementation, and

2. How businesses choose to respond—by absorbing the cost or passing it on to consumers.

Let’s break it down.

The Inventory Question: How Much of a Buffer Do We Have?

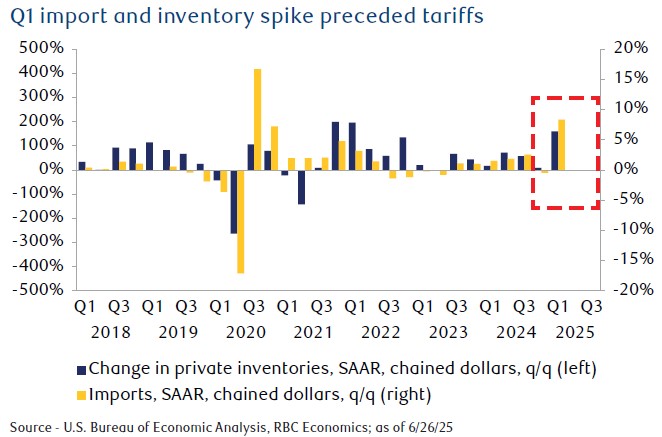

When tariffs are announced, businesses often respond by front-loading imports—ordering extra goods before the higher duties kick in. That’s exactly what we saw earlier this year. In Q1, U.S. businesses ramped up imports significantly, leading to a sizable build-up in inventories.

In the short term, this stockpiling delays the inflationary and growth-dampening effects of tariffs. Companies can continue selling goods at pre-tariff prices, shielding consumers from immediate cost increases.

But how long can that last?

Estimating the timeline is tricky. For one, inventory levels vary by sector. Durable goods like metals, machinery, or auto parts can sit in storage for months. But non-durables—like food or pharmaceuticals—expire more quickly, offering a shorter buffer. Recent data shows increasing stock in categories like fabricated metals and appliances, though we suspect the true buildup may be underreported.

There are also data complications. The official statistics on inventories often lag the real-time economy, and goods stored in bonded warehouses (not yet cleared for domestic use) may not show up in traditional inventory figures right away. These factors make it hard to pinpoint just how long the buffer will last—but our best estimate is up to five months, varying by sector.

What Happens When Inventories Run Out?

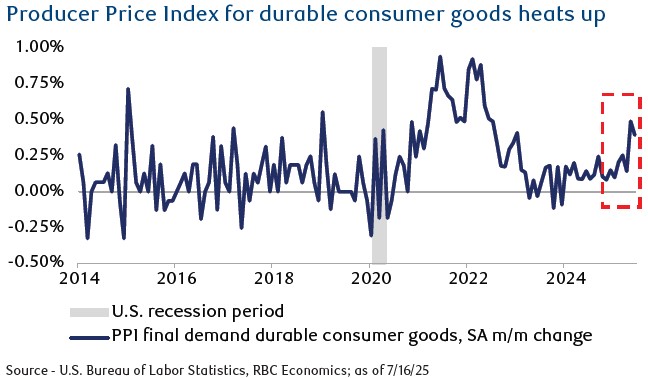

Once companies work through their existing stock, they’ll have no choice but to resume importing at higher, tariffed prices. At that point, inflationary pressures will begin to show more clearly in the data.

We expect this will start to appear in the Producer Price Index (PPI)—which tracks what businesses pay for goods at different stages of production (raw materials, intermediate inputs, and final goods). Already, we’re seeing price increases in finished durable goods, like furniture and electrical appliances.

Eventually, these increases will show up in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) as businesses pass costs on to shoppers. Sectors that are heavily import-reliant—such as household furnishings, apparel, and consumer electronics—will likely feel it first.

Who Bears the Cost? Businesses or Consumers?

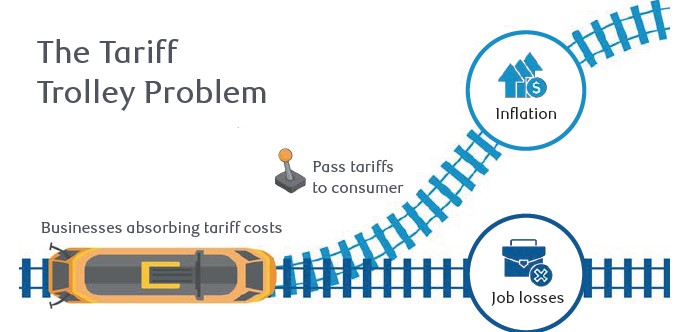

Tariffs raise costs, but someone has to pay them. The burden will likely be shared—but how it's split has major implications for the broader economy.

Option 1: Businesses absorb the cost

If companies decide to eat the added costs, their profit margins will shrink. To protect their bottom line, many may look to cut costs elsewhere—and labor is often the first to go. A pullback in hiring or even layoffs could follow, contributing to a gradual rise in the unemployment rate.

However, today’s structurally tight labor market means firms may be reluctant to make deep cuts. They might instead reduce capital investment or raise prices gradually in other parts of their business.

Option 2: Costs passed to consumers

Alternatively, companies may choose to pass the costs along, raising prices. This could worsen inflation—particularly in goods that are heavily tariffed. Higher-income households are more likely to absorb these price increases, but low- and middle-income consumers, already stretched from earlier inflation waves, may pull back on spending.

In the months ahead, we’ll likely see early signs of tariff pass-through in core goods categories. Sectors like apparel, furnishings, and electronics—many of which rely on Asian imports—are especially exposed. Further downstream, tariffs on inputs like semiconductors or vehicle parts could raise service costs (e.g., auto repairs), eventually feeding into things like insurance premiums.

A Dual Threat: Higher Prices, Slower Job Growth

The risk isn’t just inflation—it’s inflation paired with weaker demand and rising unemployment, a hallmark of stagflation.

We expect both cost-absorption and price pass-through to happen simultaneously across different sectors. That means:

- Businesses will face tighter margins

- Some will cut jobs or reduce hiring

- Consumers will pay more, particularly for goods

- Real demand may fall as households reprioritize their spending

We're already seeing a rise in precautionary savings, suggesting consumers are bracing for tougher months ahead.

By the end of the year, RBC Economics projects:

- Core goods inflation will rise to around 3.4%

- Unemployment will increase toward 4.5%

That’s not a full-blown recession scenario—but it does signal a slower, more fragile economic backdrop, especially for sectors exposed to global trade.

Final Thoughts: Navigating the Tariff Fallout

Tariffs are more than just a political tool—they’re a powerful economic force. While their effects won’t be felt overnight, the dominoes could begin to fall. Once inventories thin out and businesses are forced to react, we expect signals to show up in inflation data, employment trends, and consumption behavior. With that said, the level of tarrifs have come in lower than originally threatened as exemptions and tariff pauses continue to be offered. The risk of immediate tariff disruption has somewhat faded as the prolonged negotiations have given businesses more time to plan for contingencies and strategies to maintain margins. Moreover, the resilient economy that we have witnessed could be sustained with a level of unemployment that continues to be below historic norms, and the expectation for future rate cuts that would both relieve borrowers and reignite the housing market.

For investors and business leaders, staying ahead of these trends is critical. Watch the indicators: inventory drawdowns, producer prices, wage data, and sector-specific retail trends. These will offer the clearest window into how the tariff transmission is unfolding.