The TV commercial included a person screaming with disgust in the background while the tough-love message was delivered.

(YouTube link - 15 seconds)

As it happens, this is a pretty much bang-on description of how the economy is reacting to central bank actions so far in 2022. Financial markets – with their tendency to be myopic at times – are currently stuck on the “it tastes awful” part.

But it is working. As a starting point, preventing wages and inflation from creating an upward, self-reinforcing spiral has been priority number one recently for the Fed and the Bank of Canada. After a surge last year, wage growth is now beginning to fall back to pre-pandemic levels. Not coincidentally, it is happening in tandem with moderation in new job growth:

Left: US Average Hourly Earnings % Change MoM, 3-mo avg (May 2021-2022; orange = 2019 average)

Right: US Non-Farm Payroll Change MoM (May 2021-2022)

Source: Bloomberg, BLS

A reasonable case can be made that this trend will continue. Among large companies, a notable number have recently said that they are either slowing new hires or are outright cutting staff. Going just from memory, over the past six weeks the list includes Tesla, Netflix, Meta/Facebook, Uber, Twitter, Carvana, and Peloton. As for smaller companies, it is a little difficult to imagine that hiring plans aren’t slowing for them as well, given that their collective view of the world now looks like this…

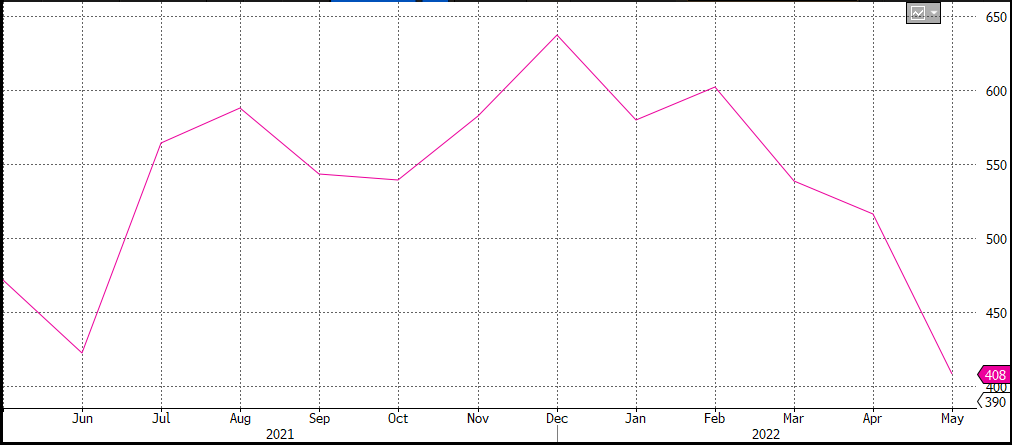

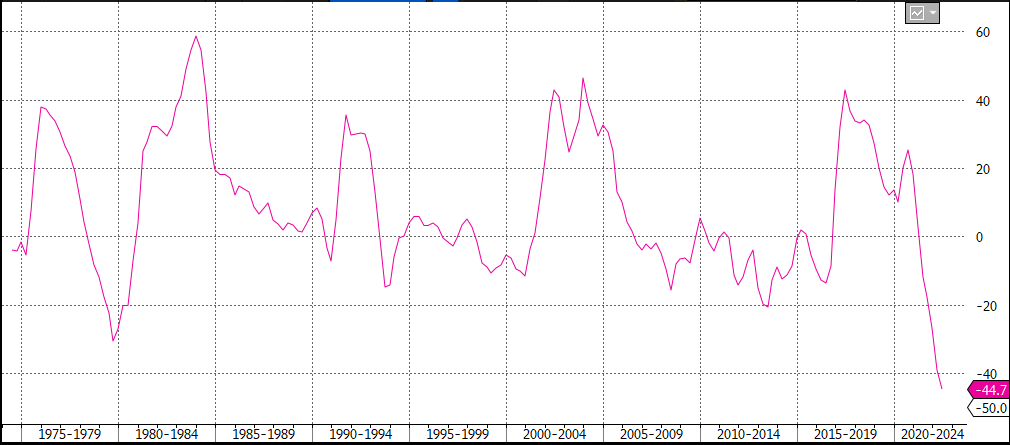

NFIB Small Business Survey – Outlook for General Business Conditions (1972 – Present)

Source: National Federation of Independent Businesses, Bloomberg

Source: National Federation of Independent Businesses, Bloomberg

Approaching inflation from a different perspective, between the data above and consumer confidence dropping precipitously in recent months, if you run a business, do you really feel that you have the economic air-cover required to keep raising prices? North America’s largest retailers certainly do not. Walmart and Target both flagged in recent weeks that they have accumulated excess inventory due to consumer demand for goods dropping rapidly this spring. As a result, they are now marking down items to right-size inventory (or in plain English, chopping prices to blow-out the excess). That will absolutely be a drag on Core inflation in May and beyond. Recall that we quantitatively explored the issue of growing inventories in Street Savvy earlier this year. Given the size of the build-up identified then, it seems reasonable to expect that this dynamic is going to play out across a broad swath of consumer-oriented businesses during the coming months.

In addition to wages and inventories, some other factors now dragging on inflation include base effects as we lap last year’s gains (ex. unless used car prices double again from here, they are now deflationary); the fact that rising prices reduce demand; the question mark on growth from China’s zero-COVID policy; and the impact already being felt in arguably the most interest-rate sensitive of industries, real estate & construction. On that last point, anecdotally, every one of our team’s real estate development contacts in Canada and the US has said that new projects across the sector are “on pause” as the risk and profitability of moving forward are being re-evaluated.

In summary, for those who want to look beyond last week’s headline CPI figure – which by definition is backward-looking – there are clear signs of deceleration for inflationary forces.

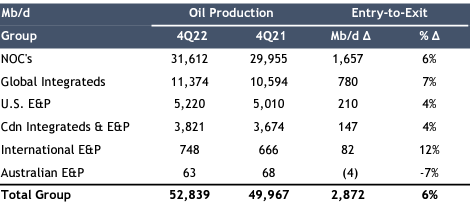

The obvious exception to this point is energy prices. Logistical issues remain for global energy markets as they adapt the sanctions on Russia, particularly around the supply of specific feedstocks for refineries, which in turn is impacting the production of fuels like gasoline and diesel. At the same time, the popular narrative in financial media that oil producers are not increasing production in response to higher prices is just not true. RBC Research – which tracks spending budgets of oil producers that in aggregate account for 70% of global production – shows the supply of crude growing by almost 3 million b/d this year (see table below). Some of that supply is obviously coming from OPEC nations, but over a third of the growth will be from public companies. In addition, as unlikely as it may have seemed earlier this year, one does have to question whether Saudi Arabia might opt to further increase supply – perhaps catalyzed by a mixture of US political incentives ahead of November's mid-term election and a recognition that a global recession isn’t good for long-term business. There is no compelling way to handicap the odds on that sort of surprise, yet it does not seem appropriate to assign it a 0% probability.

Entry-to-Exit oil production (end of 2021 vs. end of 2022)

NOC’s = National Oil Companies (ex. Saudi Aramco). Source: RBC Capital Markets, FactSet, Bloomberg, company reports

Packaging this all up, you would think that it points towards a horrific outlook for stock markets. But does it? For context on that, it is informative to review the unquestionably most dramatic era of using interest rates to fight inflation: 1979-1982, when Paul Volcker became Chairman of the Federal Reserve.

First, some groundwork:

• Shortly after becoming Fed Chair in mid-1979, Volcker raised the Fed Funds rate to 20%

• That, combined with oil prices roughly tripling due to the Iranian Revolution, caused the US to enter a recession early the next year

• The Fed quickly reversed direction and cut rates in the spring of 1980, like it had so many times before. Inflation continued to climb, despite the recession

• Late in that same year, with a new President in place after Reagan’s landslide victory in November 1980, Volcker relaunched the inflation fight with a stronger resolve

• The Fed Funds rate was increased to 22%, immediately triggering another recession. This time, the Fed kept rates high and the economy stayed in recession for a year and a half. Inflation fell throughout

• Eighteen months later, in July 1982, the Fed cut interest rates substantially, signaling to financial markets that inflation expectations had been tamed and the fight was over

Most of us either have heard stories or actually lived through the financial trauma from this period: the unemployment rate rose to 11%, GDP dropped by a percentage not exceeded until the Financial Crisis, and some families “just handed the bank their keys”. Given the chain of events, one might reasonably assume: 1) that 1980 was an ugly period for stock markets; and, 2) that November 1980 through July 1982 was an absolutely horrific period for stock markets. If so, one would be dead wrong on the former and only a half-right on the latter:

S&P 500 price chart: 1980 (price return = +26%)

S&P 500 price chart: Nov 28, 1980 – Aug 12, 1982 (price return = -27%)

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

The reason one would only be half-right on the latter is that while a 27% decline in equity markets stings, it is about typical for a recession...not horrific. It is also a mere 5% more than the drawdown that stock markets have experienced in 2022 (as of writing).

Even more interestingly, the bounce off of the bottom in August 1982 was so fast that if you had hesitated by even just a couple of months, you’d actually have been better off by investing at the tippy-top high in November 1980 and simply riding out the storm. Here is the same chart as above, with an extra few months:

Right: S&P 500 price chart: Nov 28, 1980 – Nov 28, 1982

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

To be clear, unemployment was still rising and mortgage rates were still above 18% during those two months in which the stock market recouped all of its losses, so it wasn't a dead-obvious moment to buy. Also, the chart above is not cherry-picking a special date range…the S&P kept going straight up afterward, ultimately gaining more than 200% in the following five years.

There are at least two important takeaways from this: 1) that the value of a non-speculative company far exceeds what might happen to its profit during a very bad year or two; and, 2) that it is exceedingly difficult to “time the market”.

Returning to the present day, clearly equity markets are focused on the “it tastes awful” part right now. With passive index investing accounting for over half of the money in stock markets, there is a reasonable probability that this reaction could go on for a bit…even if only due to new retail investors taking their money back out the market. After all, we live in a world where a rap star can declare a recession to her 23 million Twitter followers and the US Treasury Secretary gets asked for a reply. On a more conventional note, the recent multi-sigma price movements in major global assets like the Yen and US Treasuries are bound to lead to some portfolio size reductions ("degrossing") and the odd margin call among hedge funds.

However, it is important to remember that unlike in 1980, the economy has come into this rising rate period with unemployment at historic lows, and with the starting point for interest rates being 0% rather than 8%, and without having already suffered through a decade of mental anchoring to high inflation plus stagnant growth. As a result, we are also entering the period with exceptionally strong balance sheets for banks, consumers, and corporates. The backdrop going in is a country mile better than that which Volcker had.

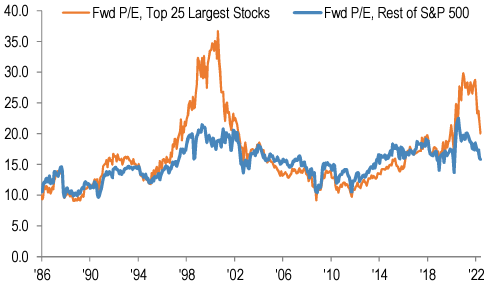

Reflecting this, corporate earnings have in fact continued to grow so far this year which means that the sell-off in equity markets has reflected a drop in valuations. In fact, after adjusting for the record amount of cash that companies currently have on their balance sheets, the forward P/E multiple for the S&P 500 is now below-average at 15x. Inverting that, the earnings yield on equities is north of 6%, or close to double the yield on government bonds. If you are an institutional investor trying to stay ahead of inflation, which of those two options are you going to prefer?

S&P 500 NTM price-to-earnings ratio (1986 – May 2022)

Source: JP Morgan Equity Macro Research

Yes, in the near-term earnings estimates will fall due to a decelerating economy and higher debt service costs. As the denominator drops, the P/E ratio will rise. But let’s not forget that investors generally value equities on forward-looking, “normalized” earnings – and as mentioned above, the prospect of a sharp recovery seems high given the strong economic backdrop going into this. All things considered, equity markets do not appear particularly expensive right now.

Our team remains of the view that the US may not even need to suffer a technical recession for the Fed to achieve its inflation goals. But even if we are wrong on that – and it’s not like we predicted a bear market at the start of this year, so clearly our powers of clairvoyance need some refining – I’m not sure it changes much at this point. The Fed is already well into the inflation battle, equity markets have already fallen an amount that is contextually similar to history, and the snap-back stands to be a fast one after the bottom does finally arrive. In light of that, the best action would appear to be simply staying the course: owning shares of non-speculative companies that can rebound nicely as the economy acclimatizes, and meantime trying to ignore the noise. For those of you who have an allocation to fixed income in your portfolios, you may see us opportunistically shift a portion of that into equities in the near term, just as we did back in April 2020.

For now, let’s all hope that as financial markets continue squirming about due to the awful taste, the Fed stays strong with administering a reasonable amount of medicine until inflation expectations are properly cured.