...1) have we arrived at “peak inflation”; and, 2) if so, is the descent for inflation that lies ahead going to be steep or shallow? While I have no crystal ball, in the prior update (Threading The Needle) we explored that simply by virtue of lapping last year’s economic reopening data, it only takes elementary math to see that the US inflation report this past month almost certainly represented the peak.

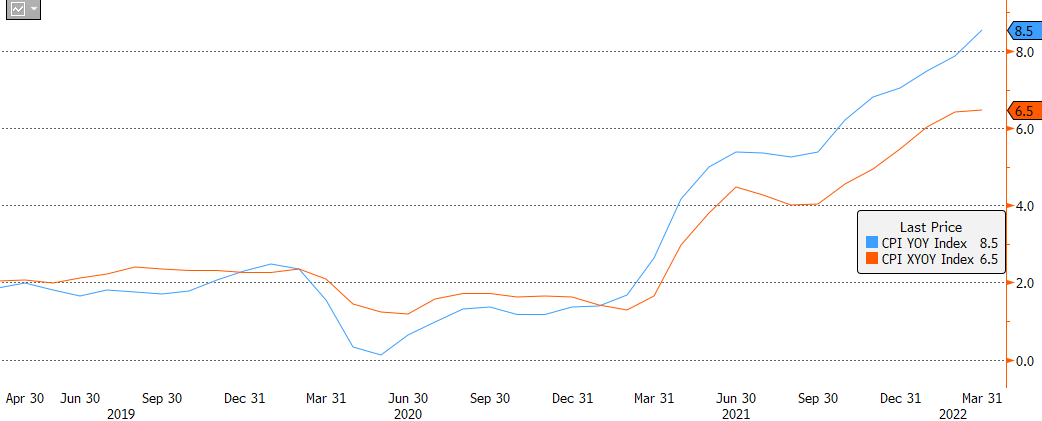

In contrast, the math on the rate of descent from here was supposed to be fairly simple as well, but then geopolitics made it complicated. This is best seen by looking at the recent gap that has opened up between Headline and Core inflation rates (Core = Headline excluding food & energy costs):

US CPI Annual % Change – Headline (Blue) vs Core (Orange): March 2019 – March 2022

Source: BLS, Bloomberg

Source: BLS, Bloomberg

Clearly, the recent surge in commodity prices is having an impact on the Headline number. What will matter from here is how much of that seeps into Core inflation over the coming months. That in turn depends on how long the war in Europe persists, whether the intensity of sanctions escalates, and also how quickly oil-rich nations (including producers in the US & Canada) shake their unwillingness to pump more crude. None of these variables are knowable.

The reason all of this matters is because central banks target Core inflation. The Fed’s concern is that it tolerated a rise in the Core measure over the past year in order to support the economic recovery coming out of the pandemic, trusting that Core inflation would then roll over quickly as they raised interest rates somewhat this year and next. But now, an unexpected supply shock to the Headline number – something over which the Fed has zero control – may keep the Core number elevated, too. Worst of all, there is no way to tell how long it may last. That could easily lead to long-term inflation expectations of consumers and businesses becoming “unanchored”, which is something the Fed is not willing to risk.

This is where a fairly boring economics discussion becomes interesting. Inflation has fundamental components (ex. supply, demand, etc.) and a psychological component (expectations, as mentioned above). If you and I are the Fed – and of course, we are not, but let’s pretend for a moment – then we know that as a rule-of-thumb it takes 18-ish months for changes we make to monetary policy to trickle through the economy and actually start impacting fundamentals. That’s great, but it does not help with our rather urgent and unexpected inflation problem today.

Solution? Focus instead on the much more real-time, psychological side of inflation by talking super-tough about quashing it. Maybe start with someone like the Fed Chair saying “No matter what happens, this is a committee that is determined to use its tools to make sure that higher inflation does not become entrenched,” (Jerome Powell, Mar 16). Then amp it up with a parade of other Committee members over ensuing weeks suggesting in various public forums that they favour rapid hikes. But let’s not stop there…if we really want to ensure that we impact the psychology of market participants around inflation, let’s then get even the most dovish Committee members who have previously shunned rate hikes to say things like, “It is of paramount importance to get inflation down...[so] we will continue tightening monetary policy methodically through a series of interest rate increases,” (Lael Brainard – Apr 5); and, “…you all have confidence that we’re not going to let this go forever; but if you don’t have that confidence, let me give it to you” (Mary Daly – Apr 5).

In other words, a useful tactic would be for us to deliver a bit of shock-and-awe to the market’s economic expectations. If the plan works, the results would look something like this:

Left: US interest rate curve, 1-year to 10-year tenor (January = orange, Current = purple)

Right: US 10-year real interest rate (real = current 10-yr rate minus expected 10-yr inflation)

Source: Bloomberg

Given those are actual charts from recent weeks, obviously the plan is working. Financial markets now believe that the Fed is going to raise interest rates more than 100 basis points above what was expected just prior to the war in Europe (left-hand chart, gap between orange and purple). Investors also perceive that the speed and size of these rate hikes will be severe enough to slow economic growth to the point that further rate hikes down the road won’t be required (left-hand chart, flatness of purple line after the first year). Most importantly for the Fed, this has also appears to have capped investors’ longer-term inflation expectations, as shown in the right-hand chart with the red circle highlighting the particular success of jawboning over the past few weeks. Alternatively, as an intuitive measure, we can see evidence of the Fed’s messaging campaign working among the broader population through things like the word “recession” surging in recent Google search-word trends.

Acknowledging all of this, you can nevertheless put me in the camp that the Fed’s bark will prove worse than its bite. Again, it only has one fast-acting tool to try to combat inflation…so why shouldn’t it use that a bit excessively right now? A more important reason, though, is because the Fed’s tough talk is intersecting with an economy that is already decelerating – a decent amount of their work is already being done for them.

To start with, Headline inflation doesn’t exist within a bubble. The same factors pushing it up are simultaneously slowing the economy. For example, the cost of gasoline at current prices and the cost of energy more broadly can be expected to shave 1% off of US GDP this year (charts below); and that is before considering the further drag from higher food prices:

Impact of price increases in gasoline (left) and broader energy (right) on real US GDP growth

Source: RBCCM US Economics, Haver

Source: RBCCM US Economics, Haver

In addition to this is the impact of higher Core inflation. While consumers remain financially healthy due to the government benefits and high savings rates that resulted from the pandemic, both of those factors are now fading in the rearview mirror. Meanwhile, core prices have risen 6.5% over the past year…so if your income hasn’t sustainably increased by that amount or more, your spending power has taken a hit.

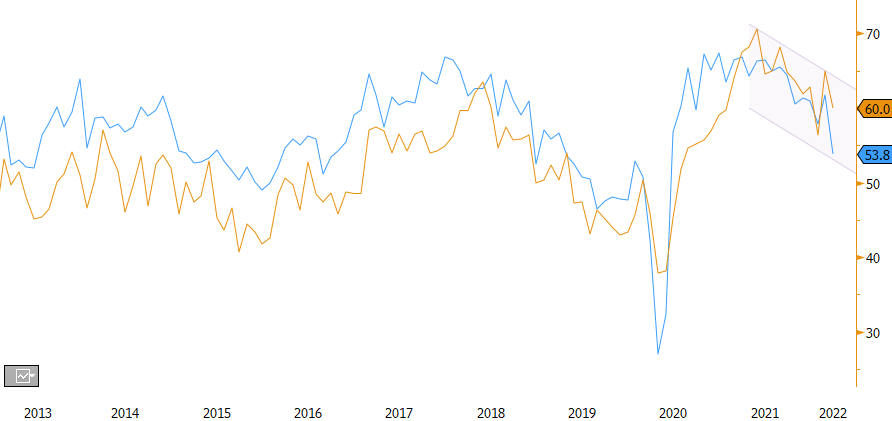

Perhaps the clearest indicator that the Fed’s goal of slower growth is already occurring, however, comes from the manufacturing sector. While still in positive territory, forward-looking data on manufacturing activity has clearly been decelerating, partly driven by a reduced need for businesses to restock inventories and partly by higher prices. Also, rather uniquely for the last decade, the outlook for new orders has fallen well below that for backlogs:

US ISM Manufacturing New Orders (blue) and Backlog (Orange): 2013 - present

Source: ISM, Bloomberg

Source: ISM, Bloomberg

All of this economic slowing is occurring independently of central banks taking any meaningful action on interest rates or the messaging of their intent to do so. Given that, it seems reasonable that while the Fed is talking very tough about inflation at the moment, when it comes to taking real action it will react to the situation on the field as the game unfolds later this year. Said differently, talking tough on inflation now buys flexibility for deciding how high to take interest rates by the end of this year and into 2023.

If that is the case, then a few things seem obvious: 1) the Fed will likely keep beating down expectations with tough talk for the rest of 2022 at a minimum, which will be uncomfortable for equity markets; 2) while a recession is not inevitable, the odds of one have certainly increased; 3) one way or another, the back of inflation is going to be broken and while it may sound crazy today, that will ultimately be bad news for recent “inflation trade” beneficiaries like energy stocks and perhaps bank stocks; and lastly, 4) the current environment demands a rethink about asset allocation for many market participants – amongst other things, bonds actually look somewhat attractive again if the narrative laid out above is correct. All of this is manageable for investors but does imply it will be a bit of a grind over the near-term for equity and bond markets to regain the ground that was lost during the first quarter.

One final thought about our home and native land specifically: how the economic tension resolves in Canada has the potential to turn out very differently from the experience in the US or globally, primarily due to the high leverage of consumers here at home. More on that in a future update.