Proof Point: University graduates are among the highest earners after completing their studies, but by one measure, the return on investing in post-secondary education has shrunk in recent years. The income earned by graduates has lagged tuition growth, particularly in fields such as engineering, architecture, and related sciences.

- Incomes are still positively correlated with attaining higher education as university degree holders earn the highest median income after graduation compared to certificate and diploma holders.

- Caps on domestic student tuition hikes imposed by some provinces in the last five years may boost the income multiple over tuitions in the future—but many other factors will be at play.

Post-secondary tuition outgrows median incomes five years after graduation

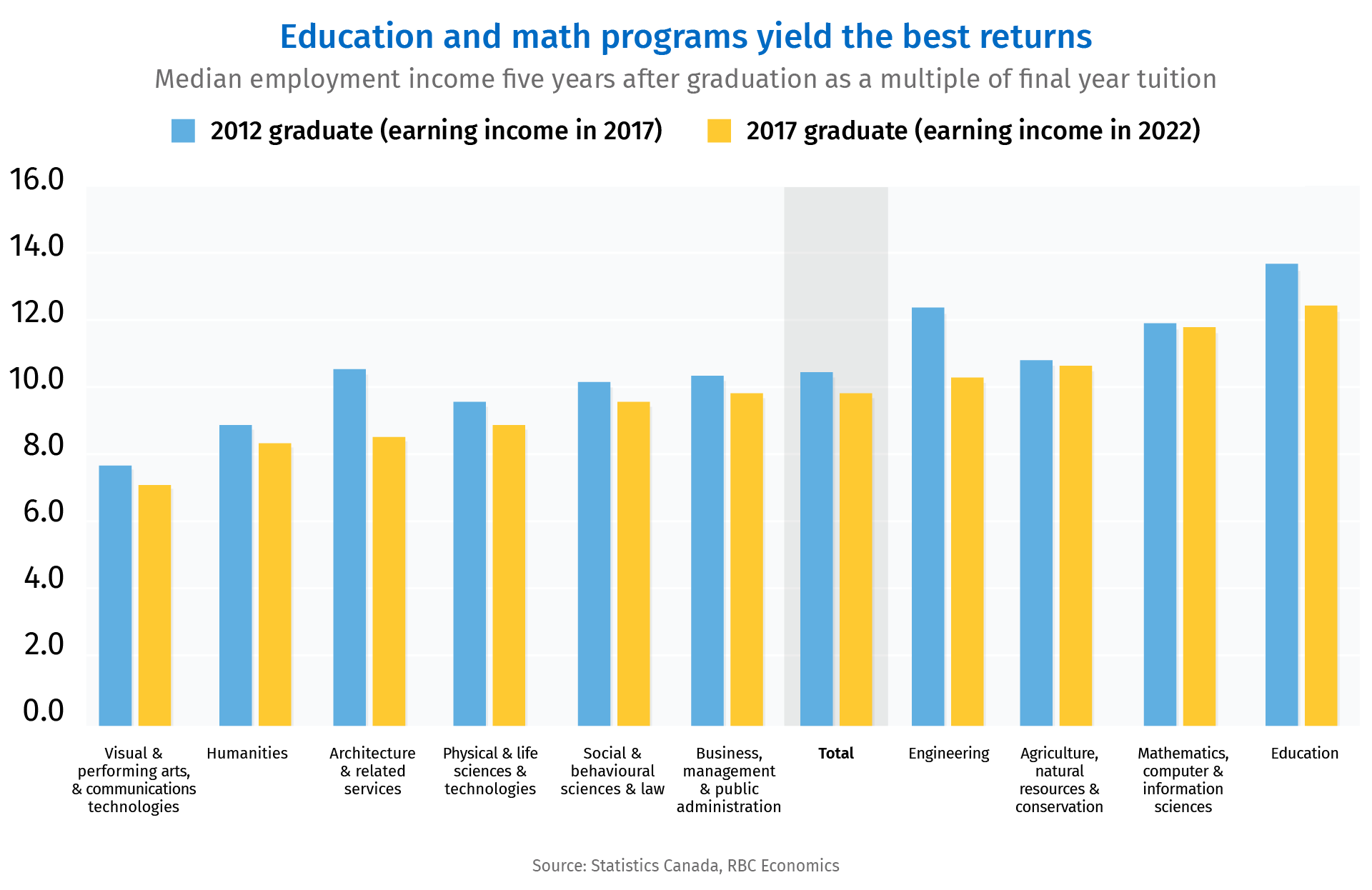

One way to measure the return on investing in an education is to compare the income earned five years after graduation with the tuition in the last year of study. In Canada, the latest cohort for whom this analysis can be done are those who graduated in 2017.

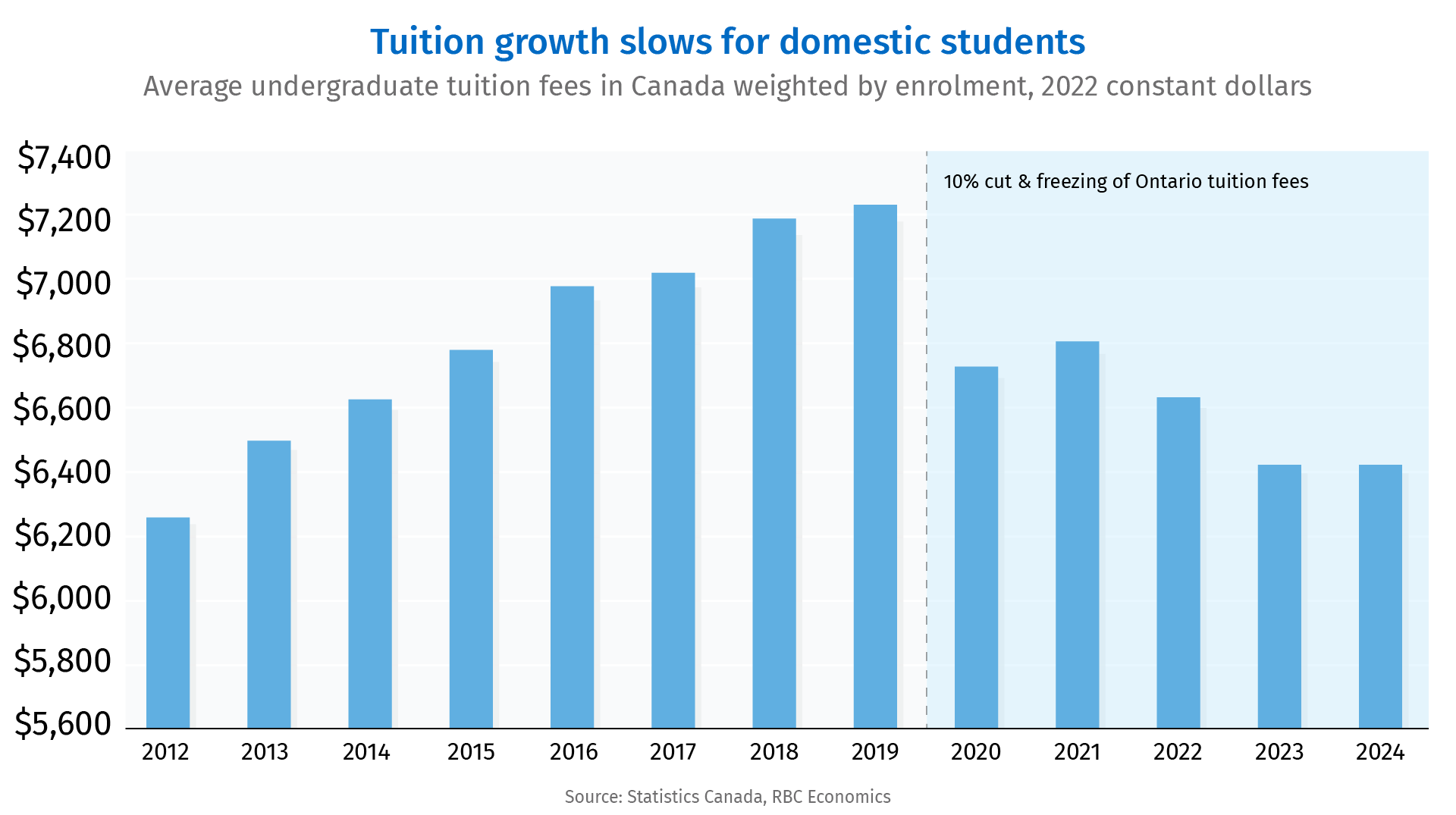

The rising cost of tuition in Canada has outpaced median income growth for post-secondary graduates five years after they completed an undergraduate university degree. After adjusting for inflation, tuition rose 12% between 2012 and 2017 for all undergraduate studies, while the median income for graduates rose just 4% from 2017 to 2022. The gap is more pronounced for engineering, architecture, and related science graduates when final year tuition increased faster than in other fields.

Median incomes five years after graduation in 2022 were 8.6 times more than tuition costs in the final year of study for architecture and related sciences. It’s a sizable decrease from five years earlier when the median wage five years after graduation (2017) was 10.6 times higher than students’ final year of tuition in 2012.

Engineering undergraduates have experienced the second largest erosion of their tuition investment with median income five years after graduation going from 12.3 times final year tuition (for 2012 grads earning in 2017) to 10.2 times final year tuition (for 2017 grads earning in 2022).

It’s worth noting that median incomes for engineering graduates are still among the highest of undergraduate degree holders—and (relative to final year tuition) provide a more generous return to tuition investment than most programs.

Incomes are positively correlated with higher education

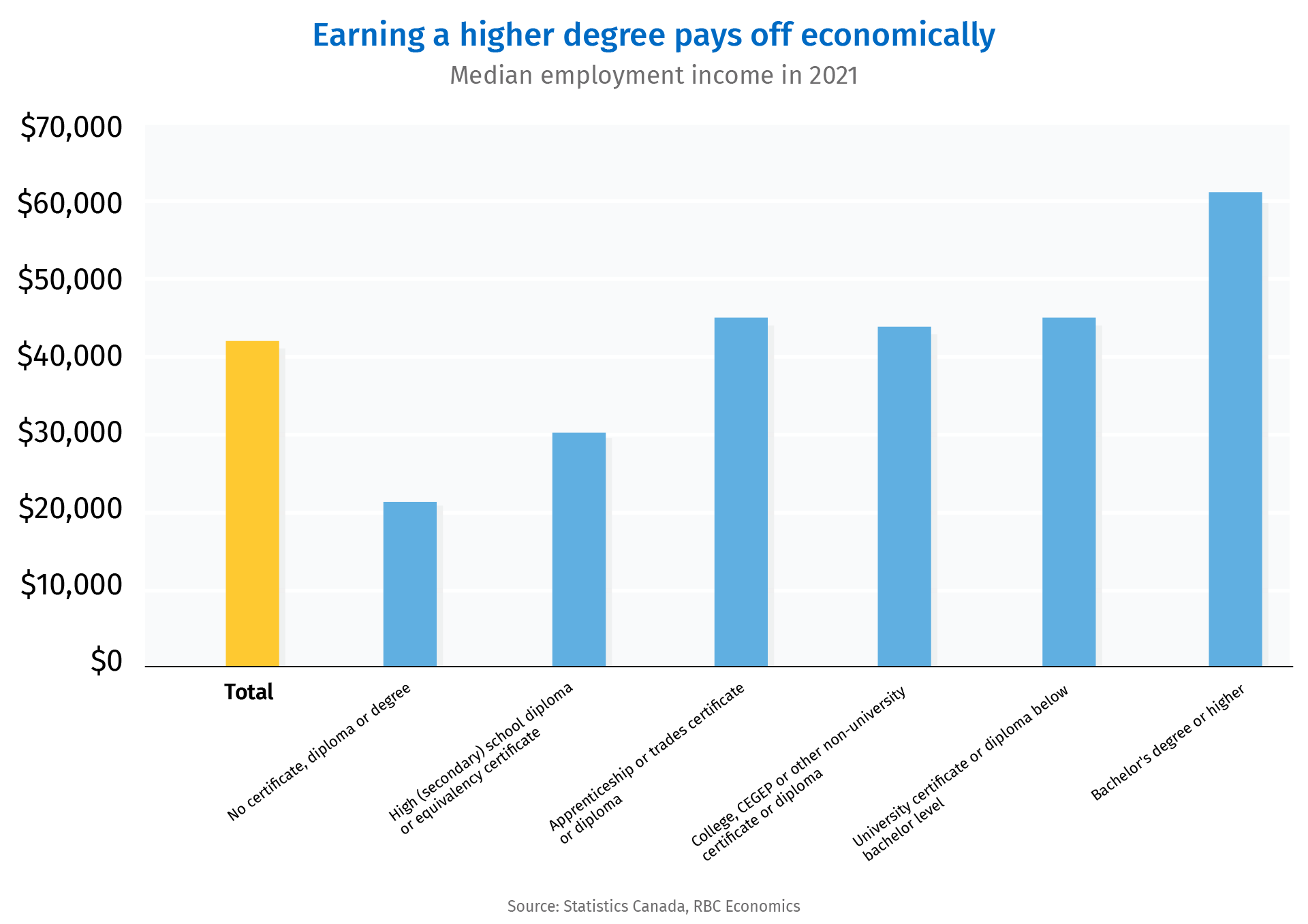

This isn’t to say returns to post-secondary education are negative in Canada. The latest census data shows a clear trend where higher educational attainment correlates with higher median income, highlighting the value of investing in higher education for financial gain.

University degree holders have and continue to earn higher wages than individuals with lower education attainment. Respondents with a bachelor’s degree or higher had the highest median income in 2021 at $61,600—44% higher than the overall median income in the sample.

Earning a high school diploma or equivalency certificate increases median income to $30,200, which is 40% higher than the median income of those without any certification. Individuals with any form of post-secondary education below a bachelor’s degree, including university certificates or diplomas, see a notable increase in median income to $45,600—51% higher than those with a high school diploma.

However, it is worth noting that for those who obtained apprenticeship or trade certificates, the median income is $45,200, just marginally higher than the $44,800 earned by those with a college diploma or CEGEP certificate. This slight difference speaks to the competitive earning potential of apprenticeship and skilled trades programs.

What tuition caps could mean for future returns

Educational attainment isn’t the only factor contributing to an individual’s income. Other influences include the general state of the labour market, broad macroeconomic policy, the quality of education, and specific job experiences. Therefore, it’s difficult to predict whether the recent trend on the financial return of investing in higher education will hold in the future.

Still, caps on domestic student tuition hikes imposed by some provinces in the last five years may curb its trajectory.

Ontario has implemented the most aggressive measure with a 10% reduction of tuition introduced in 2019, followed by a freezing of tuition for domestic students.

B.C. also maintains a 2% cap on tuition increases, first introduced in 2005, that has been expanded to apply to more programs. Nova Scotia has the highest tuitions in Canada and implemented a similar policy with a 2% cap on increases for all domestic undergraduate students, taking effect in the 2024-25 school year. These measures may work toward boosting the income multiple over tuition for students.

International students, however, are in a more challenging position since university tuition caps don’t extend to their fees, which have continued to rise. The median income earned five years after graduation for international students has also fallen short of tuition growth.

Rachel Battaglia is an economist at RBC. She is a member of the Macro and Regional Analysis Group, providing analysis for the provincial macroeconomic outlook and budget commentaries.

Abbey Xu is an economist at RBC. She focuses on macroeconomic models as inputs into the Bank’s forward looking provisioning for credit losses and stress testing process.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.