Over the past several months, inflation has been on the minds of many investors. While lumber, gold and copper prices skyrocket, central banks including the US Federal Reserve and Bank of Canada ensure us that inflation will be "transitory"; a sentiment that runs counter to traditional notions that unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus are bound to drive prices increasingly upward. With the April 2021 headline and core inflation readings at 4.2% and 3% year over year, respectively on an annualized basis being the highest readings since the Great Recession, it's easy to question central banks' assurances. Recall as well that investors had the same prediction during the 2008 financial crisis, only for the US Federal Reserve to struggle in keeping the rate of inflation near the 2% target; And that it was April of 2020 when the world economy shut down and oil prices briefly turned negative.

So where is inflation heading and what does it mean for investors?

To understand whether we should expect, and thus protect against runaway inflation over the next economic cycle, it's important to take the short, medium and long-term upward and downward pressures on inflation into account. While it's easy to look at our current environment with a combination of constrained supply and heightened demand and expect prices to continue increasing, we should take a closer look at the reasons behind these factors, whether they should be expected to persist, and whether there are other factors that are also important to consider.

Short-Term Factors

Bloomberg recently published an article discussing how current supply shortages may stick around without igniting runaway inflation. Bloomberg executive editor Tracy Alloway spoke to a number of companies in both the United States and overseas (particularly China) about the current shortage of production inputs such as semiconductors and base metals. Basic economics suggest that when supply is constricted and demand increases, price increases in response to align the quantity demanded with the reduced quantity supplied. In reality, consumer prices are sticky - in the short-term, Alloway's discussions with producers indicated that they would prefer to become more certain of longer term demand before increasing prices.

Why? When prices permanently increase, the proceeds are typically invested in expanding production capacity. If demand later decreases after supply has caught up then consumers won't be willing to continue paying increased prices for goods. Some of the current increase in quantity demanded is a direct result of a reduction in quantity supplied throughout the course of the pandemic. Consider lumber - with no shortage of timber (raw material), there has been a supply bottleneck at the milling stage throughout the pandemic due to COVID restrictions on workers. If new mills were built in response to each existing mill having reduced capacity, we would see an oversupply of milling capacity once restrictions lifted. Also consider semiconductors - McKinsey & Company state that for semiconductor manufacturers:

"... it takes about 12 to 24 months to build a shell of a fab and install the required tools, plus another 12 to 18 months to ramp up to full capacity. And if demand falls beyond projections, or if costs exceed expectations, the anticipated returns could be much lower than expected."

With costs running into the billions of dollars to increase semiconductor manufacturing capacity, producers must ensure that any changes in demand are long-term in nature, but also that any tightening of supply is also long-term in nature. All of this to say that Alloway and many others believe that these factors will in fact be transitory, in the same way that unprecedented stimulus will not last forever.

Medium-Term Factors

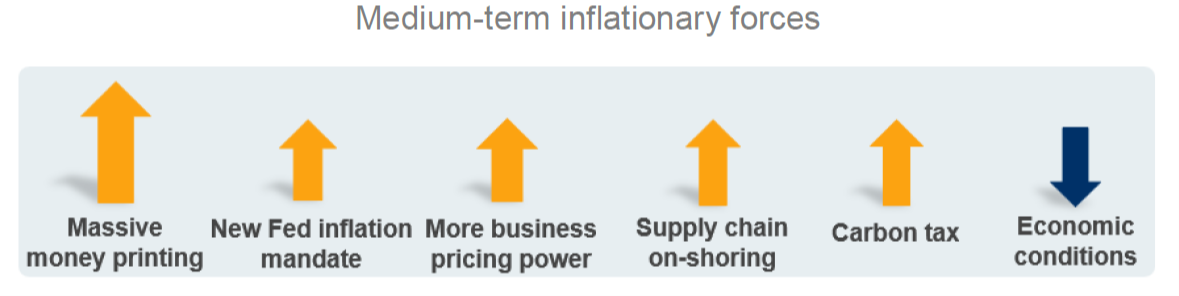

Krystyne Manzer, Vice President and Portfolio Specialist as RBC Global Asset Management wrote that in the medium-term, the amount of money being printed by central banks is arguably the biggest inflationary risk. In addition, a small change to the language around the US Federal Reserve's inflation target presents a tailwind for inflation; now targeting a long-term average of 2% inflation as opposed to the previous annual 2% inflation target, the central bank will need to overshoot the 2% level to compensate for their <2% average over the past decade. Additional factors such as supply chain on-shoring threaten to put upward pressure on prices as many goods cost more to produce in North America than overseas. New carbon pricing policies also threaten to drive up prices for carbon emitters as we transition to a net-zero economy.

Source: RBC Global Asset Management

Long-Term Factors

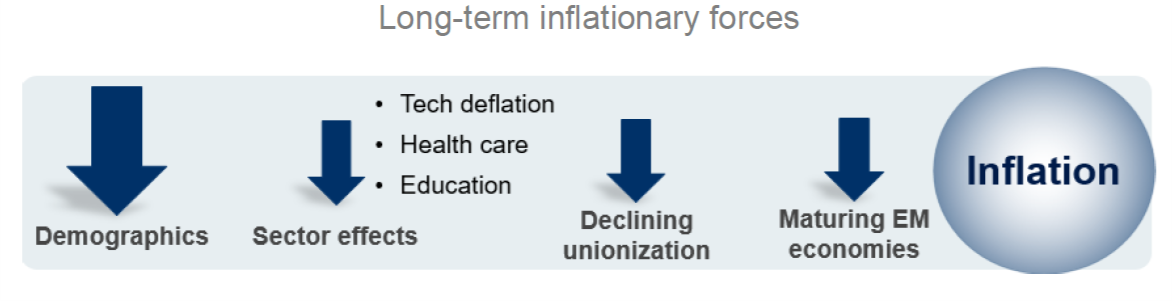

Manzer also argues that while inflationary pressures are abundant in the short term:

When it comes to investing, the longer-term forces carry greater importance and this time we see more downward forces than upward pressure on long-term inflation.

Macro trends would suggest demographic factors such as an aging population and slower population growth should present deflationary forces, as well as advancements in technology increasing productivity. The combination of maturing economies in emerging markets and expected declines in unionization as a longer-term affect of production on-shoring should also exert downward pressure. While pressure from the aforementioned short and medium term factors may exert greater force on prices over those terms, long-term trends are expected to persist long after they have abated.

Source: RBC Global Asset Management

What does it mean for investors?

Uncertainty over inflation can have a number of long-term consequences for investors when it comes to asset allocation, portfolio management and wealth planning. A basket of goods that costs $1,000,000 today will cost an additional $218,994.42 in 10 years if the average rate of inflation is in fact 2%, however that same basket of goods would cost an additional $343,916.38 vs. today if inflation runs at an average of 3%; an effect that is amplified over longer periods of time. Inflation that runs above or below the target can have equally important implications when it comes to the performance of different asset allocation strategies over both the short and long-terms. It is important that investors and their advisors plan for a multitude of inflation outcomes to fully understand their risks.