An ongoing, multipart series from RBC Wealth Management is examining various aspects of the U.S. election and the investment implications. In the second article of the series, we argue that the checks and balances built into the federal government’s structure are still relevant at a time when the country is deeply polarized.

Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump have very different views on a host of issues, including those that matter to the economy and stock market and those that don’t.

Harris and Trump both doubled down on their own ideologies with their choices of vice-presidential running mates. While Minnesota Governor Tim Walz on the Democratic side and Ohio Senator JD Vance on the Republican side were each selected to appeal to upper-Midwest swing-state voters and those who live outside of major metropolitan areas, the two differ on many issues but are in step with their respective partners atop the two tickets.

Regardless of the policy differences of the Democratic and Republican tickets, we think the main point for investors to consider is that only a portion of the winning team’s promises are typically implemented, and those are often watered down.

Following are among the key reasons why U.S. presidents don’t have free rein. We think these guardrails apply even more so during this period of deep division within the country.

Constitutional checks and balances still matter

Call us old-fashioned, we still believe that the checks and balances knitted into the U.S. Constitution by the founders, specifically the separation of powers into three co-equal branches (executive, legislative, and judicial), restrain each branch and any single individual, including the president.

The judiciary serves as an important check on presidential executive orders—directives to enforce laws and manage resources of the executive branch, including federal agencies. Former Presidents Barack Obama and Donald Trump learned this the hard way when their controversial immigration executive orders (both with polar opposite aims) were struck down in federal court, for example.

We view the often tedious and laborious American lawmaking process as positive for financial markets and investment portfolios, on balance.

While lawmaking is functionally shared by the two chambers of Congress, it also involves the president, with the latter’s responsibility to either sign congressional legislation into law or veto it. Presidential administration officials often negotiate key legislative details with Congress, and propose specific provisions.

From our perspective, this system acts as a safety valve for investors during a new president’s term by stalling or diminishing policy changes. Sometimes this delays much-needed reforms, but it also significantly reduces the likelihood a particular president or Congress can take the country in a drastically different direction in one fell swoop.

This especially comes into play when a president does not have the benefit of a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate (the agreement of 60 of 100 members to move most legislation forward). There is little chance of that occurring this election, according to recent polls, regardless of which party wins the Senate.

There was talk among some senators and political observers during the 2020 election campaign season that in the future the majority party could potentially scuttle or curtail the filibuster rule; the current rule and related procedures represent longstanding agreements among senators that are not constitutionally mandated. We think whichever party would decide to terminate or substantially alter the filibuster rule would do so at its own peril the next time the opposition party would take control of the Senate.

A “fourth branch” of power

The so-called “administrative state”—officials who serve in federal government executive branch agencies for long stretches of their careers—has more clout than is often given credit.

The Supreme Court’s recent decision to overrule Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council could constrain agencies’ power to some degree and tilts authority back to the judicial branch, specifically regarding the interpretation of ambiguous legislation. However, the impact of the landmark ruling won’t fully be determined until many diverse legal cases work their way through the courts over a number of years.

A separate effort by conservative policy group Heritage Foundation seeks to rein in federal agencies’ authority significantly as part of its controversial Project 2025 initiative. While the Trump campaign recently disavowed Project 2025, we think some of those who participated in it could be part of a second Trump administration. Nonetheless, we don’t think there are realistic prospects to achieve a comprehensive revamp of agency authority anytime soon. Efforts to do this would likely attract multiple federal lawsuits and the judicial system would have its say.

We don’t think there are realistic prospects to achieve a comprehensive revamp of federal agency authority anytime soon, despite the Supreme Court’s so-called Chevron ruling and the Project 2025 initiative.

Outside of the formal administrative state, some former officials have more sway in Washington than is commonly understood. Here we’re referring to former presidential cabinet members and retired heads and deputy heads of federal agencies; retired generals, admirals, other national security officials, and senior diplomats; some former high-ranking House of Representatives and Senate members; and former presidents and vice presidents. They are all part of the informal Washington power structure and decision-making process, like it or not.

The loud voice of corporate lobbyists and special interest groups

Another important and often overlooked guardrail is the collective voice of business interests.

One can argue whether this is good or bad, on balance, for the country and the bulk of its citizens. There are many times we think it’s good, and others when we think it’s bad. Regardless, corporate lobbying efforts are often good for stock prices within key industries.

We’ve yet to witness a single legislative cycle and presidential term when business and other interest groups didn’t achieve at least some of their lobbying objectives, often to the benefit of investors.

In two recent presidential terms, for example, controversial initiatives such as Trump’s tariffs against China and Obama’s health care reforms (the Affordable Care Act) were meaningfully shaped by give-and-take negotiations with the corporate sector. There were times when these issues generated enough market volatility to push the S&P 500 and other major U.S. indexes lower and jolted certain sectors, testing investors’ nerves and resolve. In the end, compromises were struck to the satisfaction of multiple corporate (and thus shareholder) interests.

We would not underestimate the business lobby’s significance nor creativity. From our vantage point, the industries and interest groups listed below are among those that have considerable influence in Washington D.C. They have the ears of many in Congress and key players in each presidential administration, and we think they have the ability to shape legislation and presidential directives going forward.

Powerful Washington lobbying groups that can influence legislation pertinent to industries within the U.S. stock market

- Large technology firms

- Financial services companies, including banks and insurers

- Military weapons contractors

- Foreign governments that lobby for U.S. weapons and military-technical support

- Oil and natural gas firms

- Green technology firms and environmental advocacy groups

- Conglomerate and other manufacturing firms

- Pharmaceutical companies

- Health care insurers and providers, including hospitals and nursing homes

- Large agriculture firms and agriculture advocacy groups

Source - RBC Wealth Management

Divided government is the norm

In the modern era, gone are the days when one political party dominated control over the presidency and Congress for long periods of time.

“Gridlock” or “divided government” occurs more often than not.

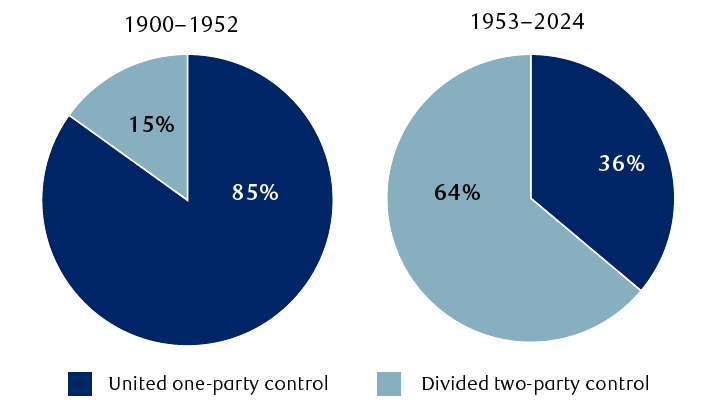

From 1900 to 1952, one-party control of the White House and both chambers of Congress occurred 85 percent of the time. However, since Dwight D. Eisenhower was sworn in as president in 1953, full control of the White House and both chambers of Congress occurred only 36 percent of the time.

And in recent decades, even when one party did have control, it didn’t last long. The five previous presidents—Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden—each governed when the opposition party controlled the House or Senate or both chambers of Congress during part of their presidential terms.

Big power politics: The landscape shifted a long time ago

From 1900 to 1952, united one party control occurred 85% of the time and divided two-party control occurred 15% of the time. From 1953 to 2024, united one party control occurred 36% of the time and divided two-party control occurred 64% of the time.

“United one-party control” is the same party controlling the White House, House of Representatives, and Senate. “Divided two-party control” is when one party controls the White House and the other party controls the House or Senate or both.

Source - RBC Wealth Management, Library of Congress, Wikipedia

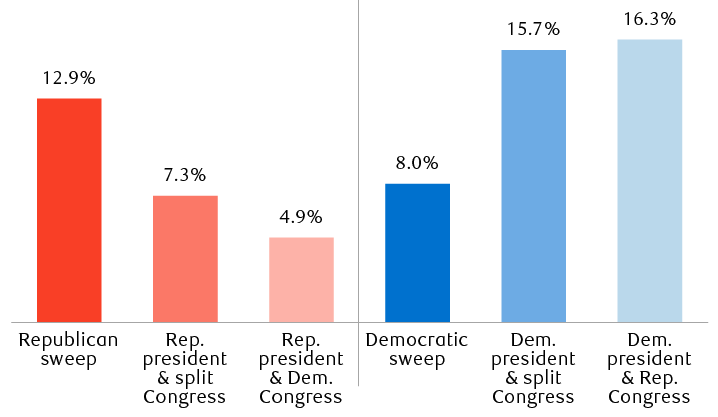

When we drill down into the divided-control period starting in 1953, there were certain market performance patterns:

- The S&P 500 tended to perform best when there was a Democratic president and Republicans controlled the House and Senate; the market gained 16.3 percent, on average.

- When there was a Democratic president and a split Congress the market also did very well; it rose 15.7 percent, on average.

- And the market performed quite nicely under full Republican control of the White House, Senate, and House; it rose 12.9 percent, on average.

But there’s an important caveat about all of this: These categories don’t include a lot of data, so they are not “statistically significant.” One big rally year or one big selloff year can change these averages notably, and quite often significant swings in the market have historically had little to do with political party control or developments in Washington.

Elephant or donkey—or both?

Average annual S&P 500 returns since 1953 by party control

Column chart showing historical S&P 500 annual returns under various party control scenarios of the federal government. Returns are as follows. The S&P 500 rose 12.9%, on average, during periods of a Republican sweep (when the party controlled the presidency and both chambers of Congress). It rose 7.3% when the Republicans controlled the presidency and control of the Congress was split between Republicans and Democrats. It also rose 4.9% when Republicans controlled the presidency and the Democrats controlled both chambers of Congress. It rose 8.0% during periods of a Democratic sweep. It rose 15.7% when Democrats controlled the presidency and control of Congress was split between Republicans and Democrats. It rose 16.3% when Democrats controlled the presidency and Republicans controlled both chambers of Congress.

Source - RBC Wealth Management, Bloomberg; data through 12/31/23; based on price returns (does not include dividends)

A president’s pull only goes so far

The media, both mainstream and alternative varieties along the ideological spectrum, are adept at elevating the importance of U.S. presidential elections and amplifying policy differences between the two major candidates.

The person occupying the Oval Office certainly has great influence and can help or hinder the country’s economic progress. However, many other factors also determine economic activity and U.S. asset class returns.

We think the U.S. stock market is usually less impacted by presidential achievements and missteps than investors might think.

This is because the formal and informal checks and balances built into the government’s structure typically constrain presidents from fulfilling the full slate of policy goals, and we think this applies even more so during this period of deep polarization within the country. Historically, the checks and balances have often worked in the stock market’s favor.

Additionally, the business cycle—the natural ebb and flow of economic activity from recovery, to steady growth, to recession, and back—the U.S. Federal Reserve’s monetary policies, and industry innovation tend to impact the stock market far more than election results, as we explained in this report. Developments in slow-moving Washington D.C. can stir up a lot of noise at times, but in our view they don’t make or break America’s behemoth $28 trillion economy.

We advise investors to not allow the din of election coverage, nor the excitement or disappointment with the election outcome, to get in the way of sound portfolio management.