New data underscore the extent of the impact, and suggest the slowdown could last for many months. Even under our most optimistic scenario, we expect that, of the 341,000 new permanent residents Canada was targeting this year, only 70% will be granted permanent residency. The reduced flow threatens to, at least temporarily, derail what’s been a major source of economic growth for Canada in recent years.

Key points:

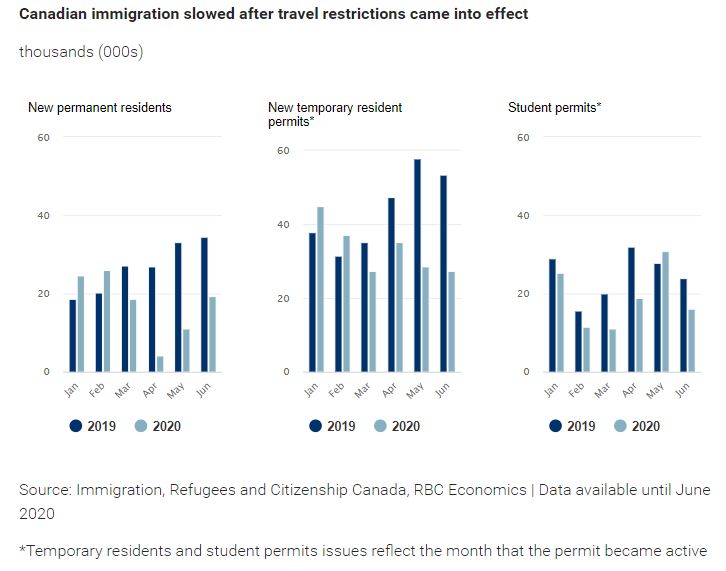

- Canada added 34,000 permanent residents in the second quarter, down 67% from the same period in 2019

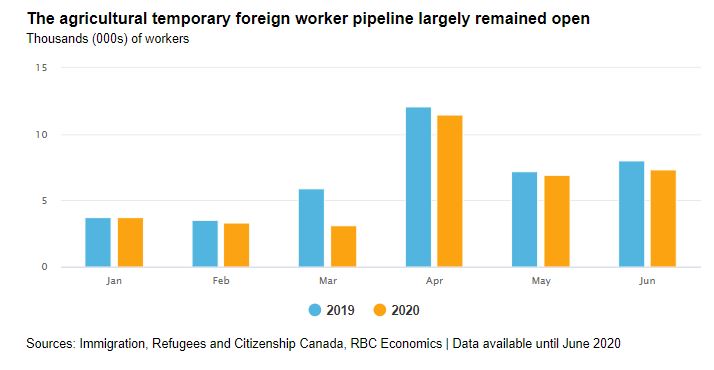

- The number of temporary work permits that came into effect was down around 50% in the quarter; permits for the agriculture sector were a bright spot

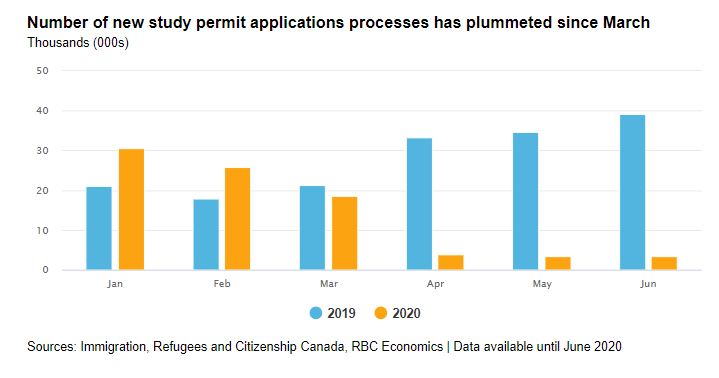

- Just over 10,000 new study permits were processed, down from 107,000 a year earlier

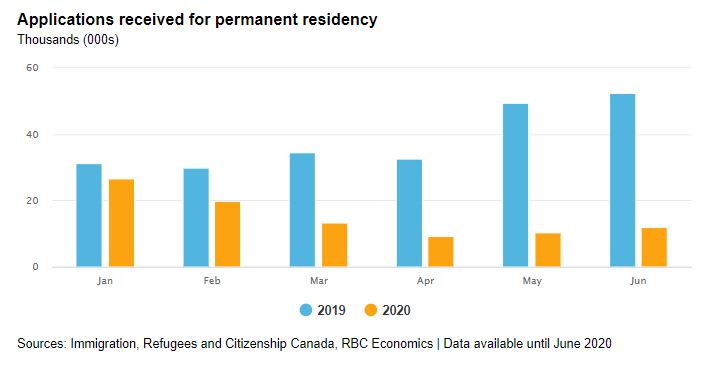

- New visa applications were down 80%, indicating the slowdown could be lengthy

- June saw signs of recovery

After a two-month drought, some green shoots in June

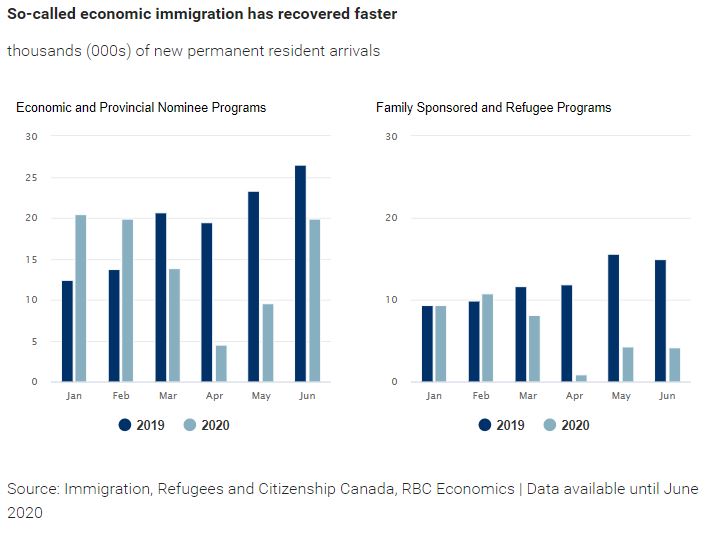

Canada experienced a broad-based decline in immigration in the April-June period, as would-be newcomers eyeing temporary work, study opportunities, or the chance to build a new life here saw their plans upended by the pandemic. Permanent-resident arrivals plunged to 34,000 in the quarter from 94,000 a year earlier—a 67% drop. June saw a partial recovery, although permanent immigration in the month was still down 44% from June 2019, reflecting the fact that travel into Canada remains restricted to those who have a permanent resident visa dated on or before March 18.

Immigration Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) approved 24,000 new permanent residents from April to June. Given that arrivals into Canada at international airports in June totaled about 4,000 people, it’s clear most of those people were already physically in Canada. Until more travel restrictions are lifted, we expect to see much lower levels of new permanent residents even as processing times improve. At the current pace, we expect only 70% of the originally planned 341,000 new permanent residents at the end of the year.

Canada was able to staff farms and greenhouses

When border restrictions were first implemented, the agriculture sector’s access to critical seasonal labour was a major concern. With some effort and financial assistance to producers, Canada was able to maintain the flow of temporary foreign agriculture workers at near-2019 levels, despite their requirement to self-isolate for two weeks upon arrival.

For other temporary foreign worker categories (such as live-in caregivers), permit approvals remained well off year-earlier levels. While demand for these workers doesn’t match the highs of seasonal agricultural work, many of these workers are employed in healthcare, particularly in caring for the elderly. Given the demands COVID-19 has placed on Canada’s healthcare sector, especially in long-term care facilities, the need for workers has never been greater, and any slowdown is likely to add to existing strains.

A robust recovery is unlikely in the near term

Data on new permanent resident applications gives us pause for the fall and winter. Visa-application centers remain closed in many countries, limiting the ability of prospective immigrants to even apply. Furthermore, the painful consequences of the pandemic, which include health concerns, increased demands on family caregivers and job losses, are likely to combine to make people less likely to seek to immigrate at the current time. That helps explain why new permanent-residency applications to Canada were down 80% in the second quarter.

Time from application to approval can take anywhere from one to two years in normal times, meaning Canada may not feel the full effects of COVID-19 on immigration until after 2020. Doubling down on programs that encourage immigrants already here temporarily—like students and TFWs—to remain permanently might be Canada’s best bet to keep the flow of immigrants high.

Of the 24,000 new permanent residents this quarter, around 58% had been TFWs, students, or in the International Mobility Program. Typically only about 20% of new permanent residents come from such temporary permit holders.

Why it all matters

Even as Canada focuses its energy to confront the realities of COVID-19, the demographic challenges of the next decade remain. High levels of immigration are required to support:

- Canada’s rapidly aging population (especially the costs of eldercare);

- the growth of Canada’s cities (disruptions may reverberate through housing and rental markets);

- Canada’s post-secondary institutions (which lean heavily on international students to fund operations)

- innovation (by drawing on the world’s best talent);

- the goal of building a diverse, inclusive Canada

The return of students remains an open question

As we head into the fall, there isn’t much clarity on the number of international students that will arrive to start the semester. The number of new study permits that were finalized in the second quarter was worrisomely low: only about 10% of the normal volume was processed compared to the same time period last year. Since July and August are historically the busiest months for new study visas, it remains to be seen whether processing rates can recover. The introduction of the two-stage approval process, which lets some students begin their studies in their home countries online without first entering Canada, may provide a buffer to colleges’ and universities’ tuition receipts until a more normalized process is in place. However, if these low numbers reflect also a steep decline in new applications – something similar to the 63% drop in temporary resident visa applications across all categories in June – then colleges, universities and the towns that house them may be in for a difficult year, financially. While disruptions to all types of immigration will prove costly, the pain caused by the failure of students to arrive is particularly acute and not something that can be made up easily in years to come. It may prove to truly be a lost year.

Andrew Agopsowicz is a Senior Economist working in both the Economics and Thought Leadership groups. He studies the labour market – largely focusing on the future of work, demographic change, diversity, and human capital. Before joining RBC, Andrew was a Senior Economist at the Bank of Canada.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.