- The Fed has broken the glass on policy tools not used since the financial crisis to ensure that markets operate smoothly amid heightened economic uncertainty.

- In order to build a bridge over the economic gulf created by COVID-19, the Fed has also introduced new tools to support the flow of credit to households and businesses.

- Though risks remain, market volatility has created opportunities rarely seen for investors over the past 30 years.

As global governments place economies into necessary states of suspended animation in order to slow activity and to minimize the public health and economic toll of COVID-19, global central banks have pulled out all of the stops—and many of the tools from the global financial crisis—to ensure that markets don’t also enter the same states of slowing, or even stopping.

With respect to the U.S. market and the Fed, it has largely focused on providing liquidity, the lifeblood of financial market function, via a renewed quantitative easing program that is now effectively limitless—meaning that the Fed will buy Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) as it sees fit until markets are “operating smoothly.” Since announcing plans to ramp up asset purchases at the beginning of March, the Fed has been buying at such a furious pace that its balance sheet has already expanded by over $1 trillion, taking it beyond the $5 trillion level for the first time.

But while buying Treasuries and MBS is the same thing the Fed did in the aftermath of the global financial crisis during its three quantitative easing programs, the new angle is that the Fed is making its first foray into buying bonds beyond government securities, by expanding its scope to corporate and municipal bonds.

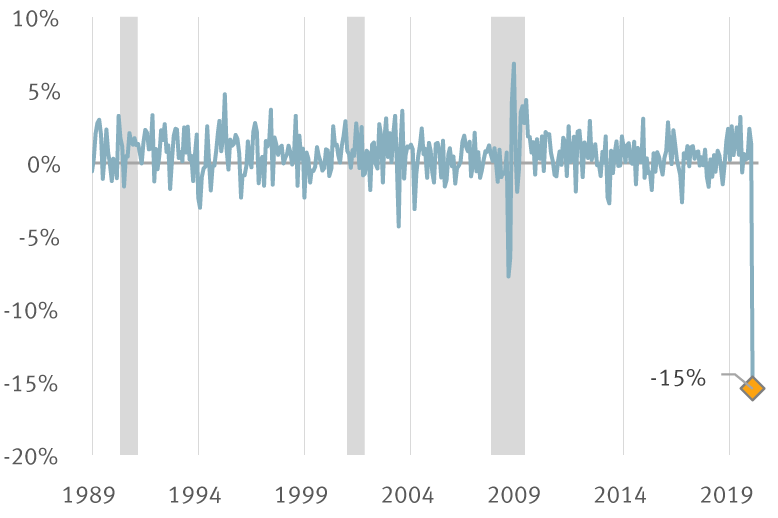

It has moved to do so because of sharp dislocations and illiquidity due to forced selling as investors fled numerous bond funds, while the economic and credit risks posed also caused significant repricing. As the chart below shows, at the nadir in March, investment-grade corporates had declined by 15 percent, eclipsing even the worst months of the global financial crisis.

Volatility hits corporate bond markets

Investment-grade corporate bonds saw their sharpest intra-month decline on record.

Source - RBC Wealth Management, Bloomberg Barclays US Investment Grade Corporate Bond Index

U.S. recessions

Investment Grade Corporate Bond Index monthly return

Lender of last resort

Though there are plenty of details still to be worked out, there was roughly $450 billion as part of the $2 trillion CARES Act set aside for the Treasury Department to backstop lending by the Fed. The thinking is that the Fed would be able to leverage that amount by about 10 times, which could create more than $4.5 trillion of financing power to buy the debt of various borrowers, which would include corporations and municipalities. To put that number in perspective, it would constitute almost a third of the outstanding debt of U.S. investment-grade corporations and municipalities, which comes to approximately $8 trillion and $4 trillion, respectively.

So that’s the “what” and “why” of the Fed’s actions, here’s a quick snapshot of the “how”:

Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility: We can think of this lending facility as addressing the “cash crunch” problem for large companies by lending directly to businesses, ensuring their access to credit. Terms will be for less than four years, loans will be open to companies rated investment-grade by the major ratings agencies, and companies will have the option of delaying interest and principal payments for six months, but will then be prohibited from buying back shares for a period of time.

Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility: This facility helps to address market functioning issues that plagued markets throughout March, with the Fed not only purchasing outstanding bonds but also shares of exchange-traded funds (ETFs), providing another source of market liquidity. The terms are the same as the Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility, but with a maximum of five years remaining to maturity. The Fed would be able to buy a maximum of 10 percent of any single issuer’s outstanding bonds, and up to 20 percent of any ETF with a broad U.S. investment-grade corporate bond mandate.

Main Street Business Lending Program: The Fed is also focused on making credit available to small and medium-sized businesses that will be administered alongside the Small Business Administration, though details are forthcoming.

These programs should be up and running in the first half of April, according to Fed plans. And while we await further details, the challenge, in our view, will be how the Fed plans to go about buying without “playing favorites,” particularly in the highly fractured muni market. With respect to corporates, any company that receives bailout money from other government programs would be excluded.

While the government stimulus packages are aimed at getting people through these challenging times and temporary job losses, the Fed’s efforts of providing credit and liquidity are aimed at bridging the gap for companies to ensure that workers have businesses to return to.

Credit where credit is due

Even though the economic and recession risks posed by the COVID-19 outbreak are virtually unprecedented, the credit risks posed to companies are the same as they usually are—it’s a matter of liquidity, not solvency. That partly explains why the Fed is focusing on buying short-dated securities maturing in less than five years, and directly lending to companies: as long as firms have access to liquidity, they should be able to manage short-term disruptions to revenues and earnings.

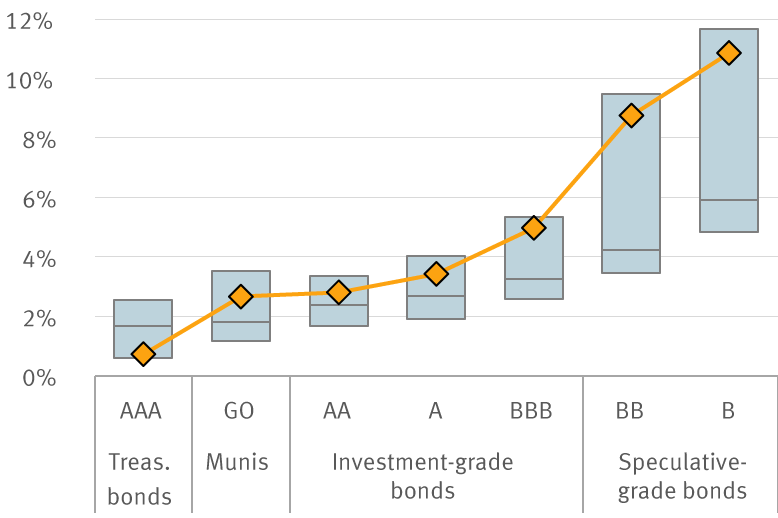

But moving to broader markets, the riskiest speculative-grade firms are most at risk, where yields have jumped beyond 10 percent, a level historically associated with distress. The long-feared risks around BBB-rated companies and potential downgrade risks have also reemerged, with the average yield on a Bloomberg Barclays index of BBB-rated companies in excess of five percent, the highest since 2009 as markets reprice for greater risks ahead.

U.S. fixed income yields remain near decade highs

Current yield

52-week yield range & average

Market volatility has pushed yields toward recent—and decade— highs.

Source - RBC Wealth Management, Bloomberg Barclays Bond Indexes

As a result, ratings agencies have sprung into action. “Fallen angels,” or companies that have lost their investment-grade rating and have been downgraded into speculative-grade territory by Standard & Poor’s have already swelled to 19 through the end of March, the fastest quarterly pace since the energy downgrade wave in early 2016.

To be sure, the Fed currently only has plans to purchase the debt of investment-grade companies. On the one hand, that may separate the haves and the have-nots, but on the other hand, it could incentivize companies with investment-grade ratings to take steps to defend their balance sheets and ratings.

But if the Fed looks set to start buying in the corporate and municipal bond markets, should investors do the same?

Opportunity knocks

“Don’t fight the Fed” was the common refrain in the years that followed the global financial crisis, and now with the Fed returning in an even bigger way—does that mantra still hold true?

Fixed income investors have been beset by years of historically low yields and relative market stability that have limited entry points into bonds at what we would view as attractive valuations. Credit investors look at credit spreads, or the excess yield over risk-free Treasuries that investors demand for perceived credit risks, in order to assess what they’re being paid to take on those risks. And with extremely elevated levels of market volatility, we are starting to see early signs of opportunity for credit investors, and at levels rarely seen as we think markets have already priced for a short-term recession.

As the table on the next page shows, investment-grade corporate credit spreads peaked at 3.7 percent in March, which falls within the three percent to four percent range, as highlighted. These types of valuations have only occurred for a total of 13 weeks dating back to 2000. And based on historical averages, investment-grade bonds have gone on to return approximately 15 percent over the following 12 months. We believe the prospects for high-yield corporates could be even better for investors with the appropriate risk appetite. Based on the same data, the current index yield advantage over Treasuries peaked at 11.0 percent in March; the sector on average tends to return over 30 percent in the 12 months that follow.

Current corporate bond valuations are favorable for investors

| U.S. investment-grade corporates | ||

|---|---|---|

| Credit spread range | Average following 1-yr total return | Weeks in range |

| 0%–1% | 3% | 210 |

| 1%–2% | 6% | 606 |

| 2%–3% | 7% | 108 |

| 3%–4%* | 15% | 13 |

| 4%–5% | 21% | 11 |

| 5%–6% | 24% | 19 |

| >6% | 27% | 4 |

| Totals: | 6% | 971 |

| U.S. high-yield corporates | ||

|---|---|---|

| Credit spread range | Average following 1-yr total return | Weeks in range |

| 0%–2.5% | -2% | 8 |

| 2.5%–5% | 5% | 488 |

| 5%–7.5% | 7% | 339 |

| 7.5%–10% | 17% | 97 |

| 10%–12.5%* | 33% | 10 |

| 12.5%–15% | 50% | 12 |

| >15% | 61% | 17 |

| Totals: | 8% | 971 |

Note: * indicates average spread range during March 2020; calculations based on weekly data from August 2000 to March 2019.

Source - RBC Wealth Management, Bloomberg Barclays Indexes

While plenty of uncertainty and risks remain, the risk/reward profiles across a wide swath of the U.S. fixed income markets have rarely been more favorable for credit investors, in our view. With the Fed on deck to begin buying corporate and municipal bonds, we think investors should do the same.

Non-U.S. Analyst Disclosure: Jim Allworth, an employee of RBC Wealth Management USA’s foreign affiliate RBC Dominion Securities Inc. contributed to the preparation of this publication. This individual is not registered with or qualified as a research analyst with the U.S. Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (“FINRA”) and, since he is not an associated person of RBC Wealth Management, may not be subject to FINRA Rule 2241 governing communications with subject companies, the making of public appearances, and the trading of securities in accounts held by research analysts.

In Quebec, financial planning services are provided by RBC Wealth Management Financial Services Inc. which is licensed as a financial services firm in that province. In the rest of Canada, financial planning services are available through RBC Dominion Securities Inc.