Good afternoon. A bit of a longer rant today. This one is in my wheelhouse, and really irks me.

My goal is to convert the skeptic on international free trade. How’d I do?

________________________________________

“An idea is like a virus. Resilient. Highly contagious.”

“The smallest seed of an idea can grow. It can grow to define...or destroy you.”

Cobb (from the movie “Inception”).

A few years ago on a summer afternoon, I looked out into our side yard and saw our beautiful golden retriever “Toffee” barking wildly at the base of a large fir tree, staring up at a black bear sow and her three cubs. It was a sunny day, and a few of our younger kids were out on the trampoline just a few feet away. I hurried the kids into the house and rewarded our lovely pup for her heroic work.

Financial fentanyl and big yellow taxis: Our instinctive human (and canine) negativity-bias is useful, sharpening our focus in the face of danger. On the other hand, we’re often oblivious to reliably abundant staples like clean water, trees, and… free trade. As Canadian Joni Mitchell sang:

“Don’t it always seem to go, that you don’t know what you’ve got ‘till it’s gone?”

Today in 2025, unfortunatley, free trade has again fallen a little out of fashion, and trade deficits (which are more or less meaningless) are once again the big scary bear -- the boogyman we can’t readily flick.

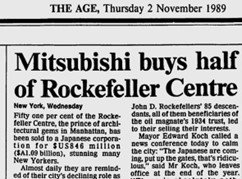

Mood Shift: In the late 80’s, Japan, with its community-driven ethic, was the great emergent financial powerhouse threatening to supersede the US. The West, and free markets in general, had limped through various depressions and recessions and had lost a measure of confidence in itself. Maybe we should be more like Japan? Did the Soviets have it right?

But Reagan, Thatcher, Mulroney and others were beneficiaries of decades of economic puzzling and enjoyed an audience ready for the counterintuitive refocus on free trade. Milton Friedman and others successfully argued for greatly relaxed global trade agreements, and against all odds won the day. These were the issues flying around just as I was finishing my finance degree.

They not only worked financially, but helped conquer the Soviet menace, helping usher literally billions out of poverty.

A couple of samples illustrate Friedman’s views on trade deficits:

“Economic growth is not about balancing trade; it’s about increasing productivity and improving living standards.”

“Most of the economic fallacies derive from the … tendency to assume that there is a fixed pie, that one part can gain only at the expense of another.”

Thomas Sowell received his Phd. under Friedman as a dedicated Marxist. (Sowell’s views later flipped, when he got a government job and saw its inherent stiff-necked approach to obvious data.)

Sowell is sort of married to data, ruthlessly takes on all comers. Read him discussing trade deficits in the conversation below with Peter Robinson:

Robinson: “How much should people really worry about the balance of trade?”

Sowell: “Somewhat less than you worry about being stuck by lightening.

Robinson: “South Korea sells 500,000 cars every year in the US (I’m not sure what year this was). The US sells only 5000 in Korea. Why shouldn’t we worry about this?”

Sowell: “Were Americans forced at gunpoint to buy these cars from Korea?”

Robinson: “Clearly not.”

Sowell: “I don’t see why third parties should concern themselves with it then.”

Robinson: “So what’s the argument on the other side (against trade)?”

Sowell: “They argue we are sending American jobs abroad... This argument was made in 1930 (referring to the Smoot-Hawley Tariffs) … and it was one of the biggest disasters in the history of the country… it was only after the government intervened (with the tariff act) that the unemployment rate shot up to 25%... So, the people out there just dying for the government to come in with their solution – I don’t know if they’ve studied history or not.”

Anyone? Anyone? Bueller? Bueller? Famously in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off a high school teacher struggles humorously to engage his students in this very discussion:

Teacher: “In 1930, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives, in an effort to alleviate the effects of the... Anyone? Anyone?... the Great Depression, passed the... Anyone? Anyone? The Hawley-Smoot Tariff Act. Which, anyone? Raised or lowered?... raised tariffs, in an effort to collect more revenue for the federal government. Did it work? Anyone?... Anyone know the effects? It did not work, and the United States sank deeper into the Great Depression.”

From the US Senate Website: On June 13, 1930, the US Senate passed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, among the most catastrophic acts in congressional history.

But we’re in April 2025, as far away from the 80’s as the 80’s was from the great depression. And despite what has been a very remarkable run overall, the reasons for the win have faded.

And in the last two days of this week, markets have digested the most recent, most articulated round of this regurgitated concept of tariffs, and doesn’t like it much.

I did get a measure of hope in these snippets from an article from the Wall Street Journal on Friday, one of many in the Journal trying to drill the points home:

“Ultimately the costs of the tariffs will be recognized, and they will be rescinded… eventually markets do recover, because over time logic prevails.” (Bryan Taylor, chief economist at Finaeon, a research firm in California.)

And here’s another hopeful one:

“You think markets are crazy today, and they are. But if you thought like a 230-year-old, all this would be a lot less surprising…

“Most investors today would be shocked by how much more of a circus this country’s financial markets have been in the past… This will be painful, but we will get through it.”

(Mark Higgins, author of “Investing in U.S. Financial History,” a book that chronicles markets from 1790 to the present.)

________________________________________

Not Convinced Yet?

Did Canada’s early fur traders rip off their European buyers by not turning around and buying suits and hats and, crochet sets and whatever else from Europe? No, no, and no. In effect, the developmental mismatch was the reason each party got the best deal available, despite any trade imbalance.

Moving to today, the US Southwest has occasionally drooled (rightly) over Canada’s enviable fresh water supply. Canada’s water was in fact negotiated out of the NAFTA agreement as a sort of nationally sacred item, but ignoring this, it’s not out of the question that it could somehow be renegotiated.

Assuming we figured out a way to minimize environmental impacts at this end, much to the delight of the US Southwest, let’s say we agreed to sell them $10 billion of water annually, would this imply we have to spend that $10 Billion in the USA? Or does the trade itself mutually satisfy the reciprocity? Obviously the trade itself satisfies both parties.

Is this getting obvious yet? No? Okay, try this one on:

If you buy a house from the guy across the street, freely and fairly, does he have to use the cash to buy your cars and dogs and cats and your collection of broken lawnmower parts? And if he doesn’t, is he cheating you? Of course not. The idea handcuffs the marketplace into weird and impossibly complex series of unwanted transactions – it freezes free markets, turns free trade into a tangle of zombie rules and meaningless transactions.

Okay. Last try: Why do you get excited to go to a big city? To buy cool stuff from a wider range of choices.

It’s awesome, and delicious, and only there because they are free to innovate their best product at their best price, competing against the best of hundreds, maybe thousands of other restaurants all trying to woo you in. The consumer wins.

Or we could say, the wow factor wins when the wooers wallop the whiners, with their wares -- everywhere.

________________________________________

Here’s this week’s RBC Wealth Management's investment newsletter.

Tariff deluge: RBC’s initial take:

President Donald Trump unveiled his long-threatened reciprocal tariffs, putting an exclamation point on a new era of protectionism. Our regional analysts review the tariff policies and provide thoughts on the implications for economies and financial markets.

Europe: United in adversity:

New and nontraditional rhetoric from the U.S. has galvanized European leaders. Defense spending has become a priority and this, along with a shift in German fiscal policy, should support growth. Despite the risks inherent in a trade war, we believe portfolios should be exposed to the region.

________________________________________

Charts:

Innovations like AI can disrupt the labour market but they ultimately create many more new jobs (see chart below from the Financial Times).

________________________________________

Hmm… so that’s the money goes when other countries sell their stuff to the USA: Will trade policy undermine American’s position as the investment magnet of the world? (see charts below): “The U.S. share of global cross-border investment projects reached its highest level ever in 2024 by attracting more than 2,100 new FDI greenfield projects in the 12 months through last November. A very distant second was China, which attracted fewer than 400 projects in the same period, close to a record low for the world’s second-largest economy. And so the near-term pile-into-the-U.S. investment flows remains intact and coincident with a longer-term trend: Incredibly, since the beginning of this century, the U.S. has accounted for 17.3% of the global FDI inflows. That’s well ahead of any other country in attracting investment, such as second-place China, which accounts for 8.3% of the total. “

________________________________________

Feel free to contact me with any questions and/or to discuss things.

Enjoy your weekend!

Mark

Thomas Sowell received his Phd. under Friedman as a dedicated Marxist. (Sowell’s views later flipped, when he got a government job and saw its inherent stiff-necked approach to obvious data.)

Thomas Sowell received his Phd. under Friedman as a dedicated Marxist. (Sowell’s views later flipped, when he got a government job and saw its inherent stiff-necked approach to obvious data.) Did Canada’s early fur traders rip off their European buyers by not turning around and buying suits and hats and, crochet sets and whatever else from Europe? No, no, and no. In effect, the developmental mismatch was the reason each party got the best deal available, despite any trade imbalance.

Did Canada’s early fur traders rip off their European buyers by not turning around and buying suits and hats and, crochet sets and whatever else from Europe? No, no, and no. In effect, the developmental mismatch was the reason each party got the best deal available, despite any trade imbalance. Moving to today, the US Southwest has occasionally drooled (rightly) over Canada’s enviable fresh water supply. Canada’s water was in fact negotiated out of the NAFTA agreement as a sort of nationally sacred item, but ignoring this, it’s not out of the question that it could somehow be renegotiated.

Moving to today, the US Southwest has occasionally drooled (rightly) over Canada’s enviable fresh water supply. Canada’s water was in fact negotiated out of the NAFTA agreement as a sort of nationally sacred item, but ignoring this, it’s not out of the question that it could somehow be renegotiated. If you buy a house from the guy across the street, freely and fairly, does he have to use the cash to buy your cars and dogs and cats and your collection of broken lawnmower parts? And if he doesn’t, is he cheating you? Of course not. The idea handcuffs the marketplace into weird and impossibly complex series of unwanted transactions – it freezes free markets, turns free trade into a tangle of zombie rules and meaningless transactions.

If you buy a house from the guy across the street, freely and fairly, does he have to use the cash to buy your cars and dogs and cats and your collection of broken lawnmower parts? And if he doesn’t, is he cheating you? Of course not. The idea handcuffs the marketplace into weird and impossibly complex series of unwanted transactions – it freezes free markets, turns free trade into a tangle of zombie rules and meaningless transactions.