For roughly a decade, the U.S. equity market had little-to-no competition from the U.S. bond market.

Bond yields were unusually low largely due to the Fed’s ultraloose, near-zero percent interest rate policies which suppressed yields. The S&P 500’s dividend yield was either competitive with the 10-year Treasury yield or exceeded it at times—both rare occurrences in history.

As bond yields were declining or suppressed, naturally investors often assessed the dividend yield from the equity market, combined with equities’ price appreciation potential, as a more attractive option.

During this period, institutional investors quipped that the stock market was benefiting from the TINA phenomenon—an acronym that stands for “there is no alternative” to equities.

Fast forward to 2023, and suddenly there are alternatives to stocks. TINA has competition.

Heed the yield signs

Now that the Fed has hiked interest rates aggressively, bond prices have sold off and bond yields have surged to their highest levels in many years.

As of this writing, short-term Treasuries possess yields close to and above five percent, and longer-term Treasuries are above four percent. The Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Corporate Bond Index, which measures investment-grade corporate bonds, is yielding 5.76 percent. Even banks are paying rates on money market funds that are higher than the S&P 500 dividend yield.

At the same time, as the S&P 500 has rallied recently, its dividend yield has drifted lower.

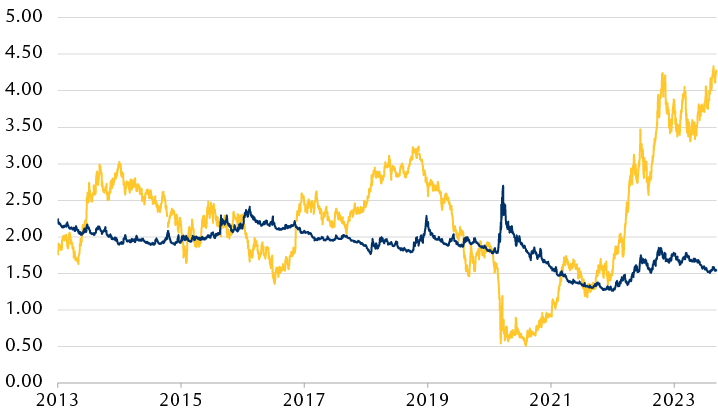

The result is that the gap between the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield and the S&P 500 dividend yield is as wide as it has been in the past 10 years, as the chart on the previous page illustrates.

The U.S. 10-year Treasury yield has surged while the S&P 500 dividend yield has drifted lower

Line chart showing the U.S. 10-year Treasury yield and the S&P 500 dividend yield since the beginning of 2013. The 10-year yield was in a range between 1.35% to about 3.25% from 2013 through 2018. Then it fell steadily until early 2020, reaching a low of about 0.5% in August of 2020. It then rebounded and surged in 2022, and it has largely traded at similarly high levels in 2023. The most recent yield is 4.28%. The S&P 500 dividend yield ranged from 1.8% to 2.3% from 2013 to early 2020. Then it briefly spiked to 2.7% in March 2020. From that time it drifted lower, reaching a low of about 1.4% in late 2021. Since then, it bounced up slightly and then pulled back again, reaching 1.55% recently. The chart shows that the 10-year yield is now much higher than the S&P 500 dividend yield: 4.28% to 1.55%, respectively.

Source - RBC Wealth Management, Bloomberg; data through 9/6/23

The difference, or the spread, between the 10-year yield of 4.28 percent and the S&P 500 dividend yield of 1.55 percent is 2.73 percent or 273 basis points.

This greatly exceeds the 10-year average of 40 basis points and is approaching the long-term average of 322 basis points that has occurred since 1971.

Furthermore, all 11 S&P 500 sectors now have dividend yields below the 10-year Treasury yield (see chart). This has not occurred in the past 10 years until very recently, but it is the more typical relationship going back decades.

All of the 11 S&P 500 sectors have dividend yields below the 10-year Treasury yield

10-year Treasury yield versus S&P 500 sector dividend yields

Bar chart showing the 10-year yield and S&P 500 sector yields on 9/6/23. The 10-year yield is 4.28%. The dividend yields for S&P 500 sectors and the index itself are: Real Estate 3.58%, Energy 3.54%, Utilities 3.54%, Consumer Staples 2.64%, Materials 2.04%, Financials 1.87%, Health Care 1.69%, Industrials 1.69%, S&P 500 Index 1.55%, Consumer Discretionary 0.89%, Information Technology 0.82%, and Communication Services 0.80%.

Source - RBC Wealth Management, Bloomberg; data as of 9/6/23

Role reversal?

As long as bond yields remain elevated and higher than the S&P 500’s dividend yield, we think investors could be more inclined to allocate a greater share of their incremental cash to bonds instead of equities—the reverse of what has occurred over the past 10 years.

In our view, this factor alone is not enough to jolt the equity market as historical data indicates the trajectory of the economy and corporate earnings play the biggest roles in shaping the equity market’s direction and magnitude of gains over the long term. But we think the potentially greater demand for bonds and relatively lower demand for equities could serve as a headwind for the U.S. equity market if this relationship persists over time.

S&P 500 returns have historically been much higher in the rare periods when the index’s dividend yield exceeded the 10-year Treasury yield, and also when the reverse extreme happened—when the dividend yield was far below the 10-year yield.

A CFRA study cited by Forbes based on data from 1953 to 2021 illustrates this relationship. It shows that historical S&P 500 returns were highest when the spread between the S&P 500 dividend yield and the 10-year yield was the widest, and returns were second-highest when this spread was very negative. (Note: The CFRA data represents average 12-month forward S&P 500 returns, measured at the end of each quarter.) The data are as follows:

- Twenty-one percent return in the S&P 500 when the spread between the index’s dividend yield and 10-year Treasury yield was greater than zero percent; this scenario was rare

- Seven percent return when the spread was between zero percent and negative two percent

- Four percent return when the spread was between negative two percent and negative four percent

- Thirteen percent return when the spread was less than negative four percent; in other words, when the dividend yield was much lower than the 10-year yield

Currently, the spread is -2.73 percent (-273 basis points), which is in the third category, where historical forward 12-month S&P 500 returns are the lowest. Based on our expectations for bond yields, the dividend yield, and the economy, we think the spread will likely be in one of the two middle categories for the time being.

This historical return relationship between the S&P 500 dividend yield and the 10-year Treasury yield is another reason—in addition to recession risks and related earnings growth vulnerabilities—why we believe U.S. equity returns next year have the potential to undershoot returns for this year.

Thus far in 2023, the S&P 500 price gain is pacing at about 16 percent and we think there is room to tack on additional gains before year-end. But next year the competition factor between stocks and bonds could kick in, and recession risks could reaccelerate.

A complement to stocks

Clearly, equities have an important place in balanced portfolios, and their long-term historical returns have far exceeded returns on bonds (although, admittedly, with higher risk and volatility). We still view the equity dividend growth strategy as the most favorable for the equity side of portfolios; historical returns for this strategy have greatly exceeded those of the S&P 500 over the long term.

But we think the current relationship between the equity market’s dividend yield and the 10-year Treasury yield along with the demise of the TINA effect are reasons for investors to take a close look at portfolio allocations and consider opportunities in bonds.

For more information about why we believe bonds are attractive, especially for balanced portfolios, see our recent article “The income is back in fixed income.”