Many jobs lost in the pandemic will be recovered relatively quickly as vaccinations ramp up and the Canadian economy re-opens. But for visible minorities and women—groups whose employment was among those hit hardest by the pandemic—a return to labour markets considered ‘normal’ prior to the crisis won’t be good enough.

As we steer closer to the end of this recession, it’s worth remembering that for these groups, a revival of the status quo will mean once again coping with longstanding employment and wage gaps that placed them at a distinct disadvantage. Closing these gaps would not only address ongoing inequities in the job market but would open powerful economic opportunities for Canada. For instance, finding ways to better engage the skills of visible minority workers could boost GDP by close to $30 billion per year.

Long-run structural labour market gaps to reappear

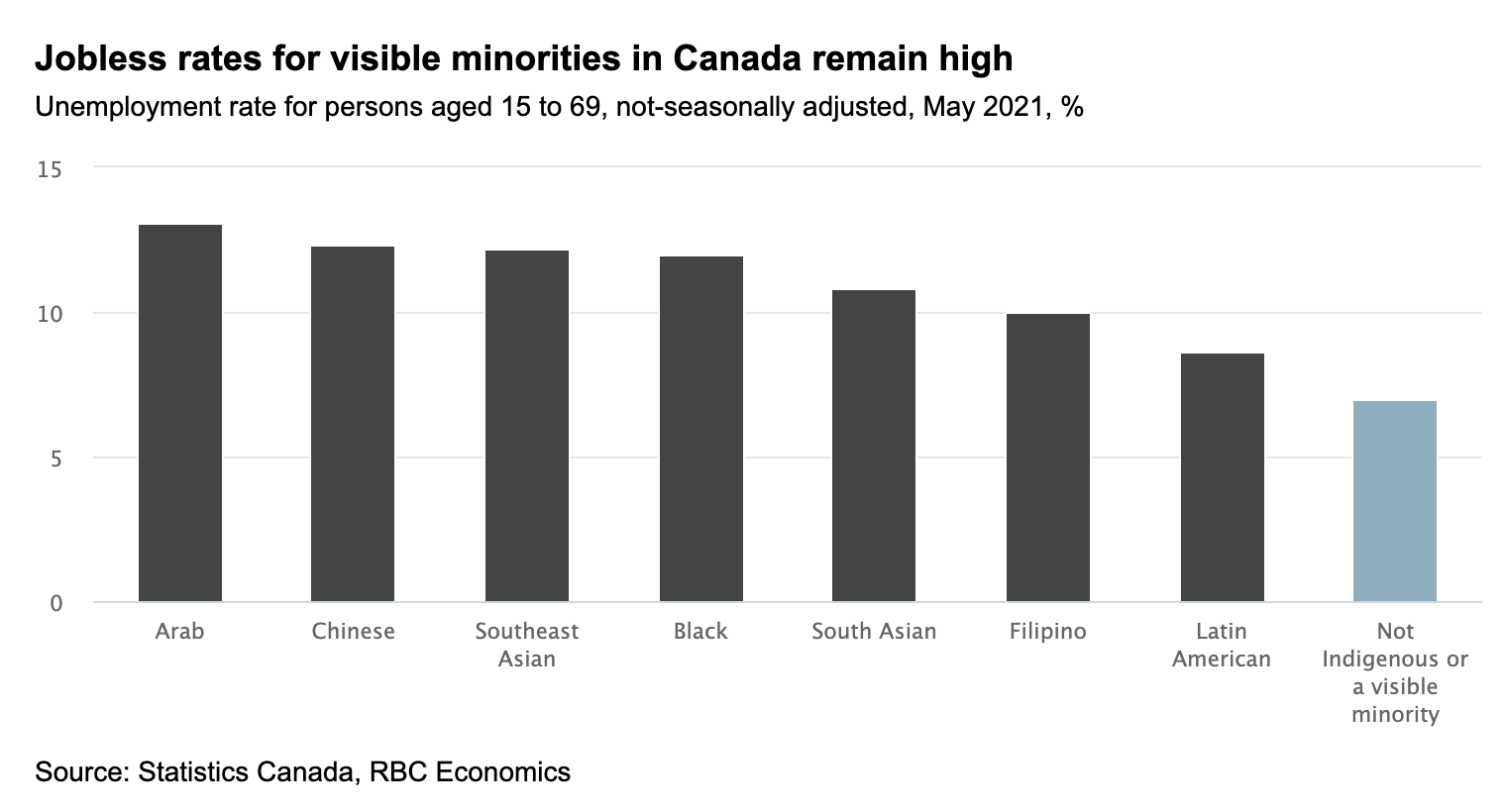

In many cases, those hit hardest by the pandemic job downturn in Canada were already struggling. The unemployment rates for some groups have long exceeded the rest of the population, and remained above national levels even when the economy was thriving. Indeed, since 2001, the jobless rate for visible minorities has exceeded that of non-visible minorities by an average two percent annually. This gap grew even wider during the crisis—with the unemployment rate hitting 16.3 percent in July for visible minorities compared to 9.3 percent for non-visible minorities. This is in part because visible minorities are over-represented in hospitality and other industries, that are among the hardest hit sectors of the economy.

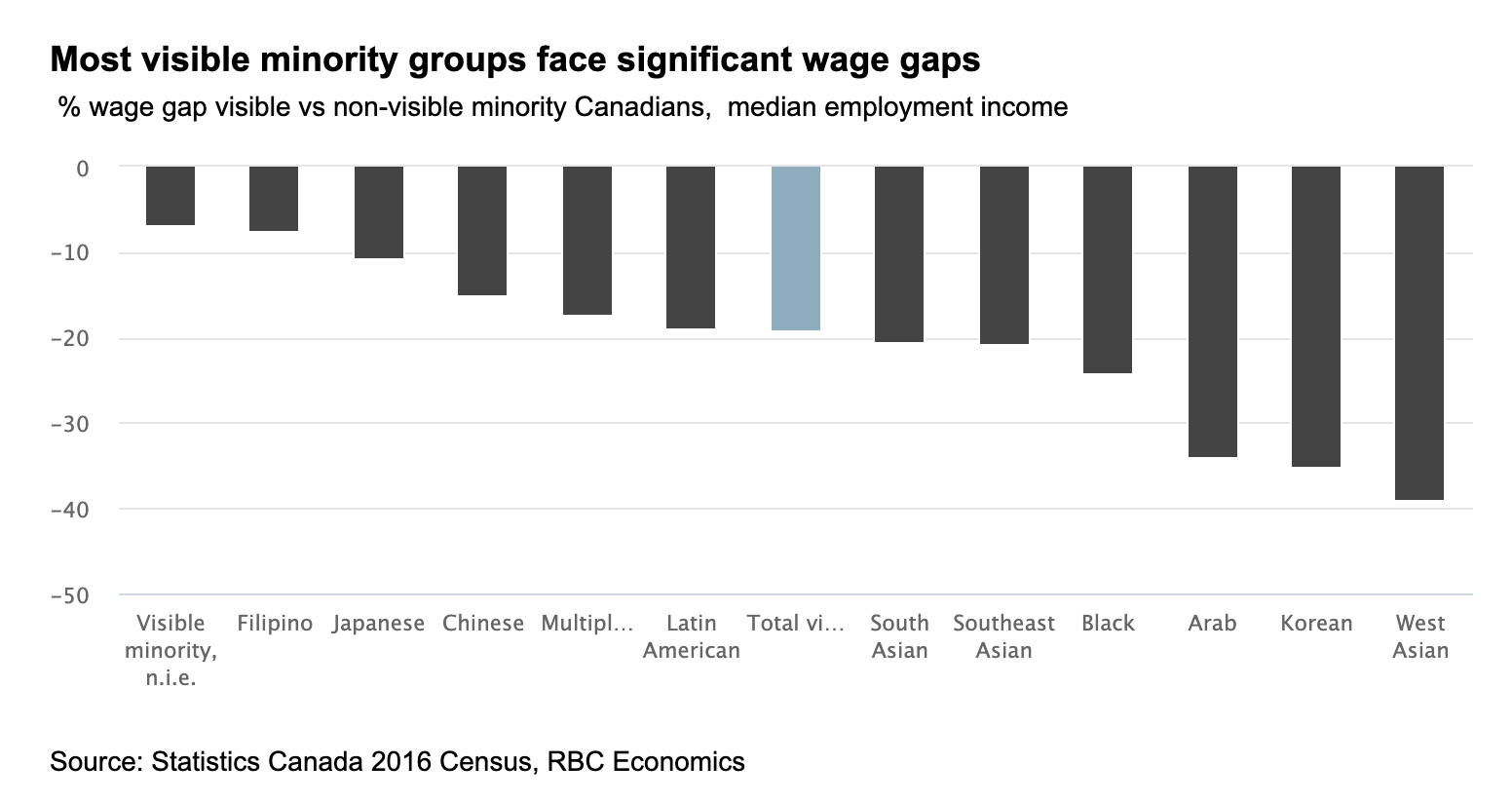

What’s more, visible minority Canadians have historically underperformed in the labour force —a pattern that translated into a total earnings gap of more than 15 percent in 2016. There is, of course, diversity among groups. Recent data shows that Chinese Canadians take home comparable wages to the non-visible minority population, although unemployment in this group is more than 2.5 percent higher in 2021. And in recent months, fewer Filipino Canadians were unemployed than non-visible minority Canadians, though this group, on average, earns sharply lower wages (as little as 76c/$1). The impact of labour market underperformance among visible minorities is significant. More than 25 percent of Southeast Asian workers earn low wages. And nearly half of all Latin American workers have trouble meeting their financial obligations.

Labour force participation among women remains persistently below that of men. This is one of the key inequities that the newly-announced federal childcare program is meant to address. But participation among visible minority women is even lower, running more than 0.5 percentage points below that of women at-large since the pandemic began. And even before the crisis, the unemployment rate for female visible minorities was over 3 percent higher than that of the broader female population. Government income supports for those losing work during the pandemic have been significant, but that aid is set to wind down later this year. At that point, there will be fewer guardrails in place to support these women that have historically been at a disadvantage.

There are substantial economic benefits to reducing structural labour market gaps

Canada stands to gain significantly if it can engage the skills of these groups. For instance, ensuring that the skills of visible minority workers are re-aligned to their most productive means—essentially better utilizing Canada’ available supply of labour—would lift GDP by nearly $30 billion per year. Making that shift won’t be easy, however. Much of the potential economic gain depends on closing a substantial wage gap that has affected many highly-skilled visible minorities and women.

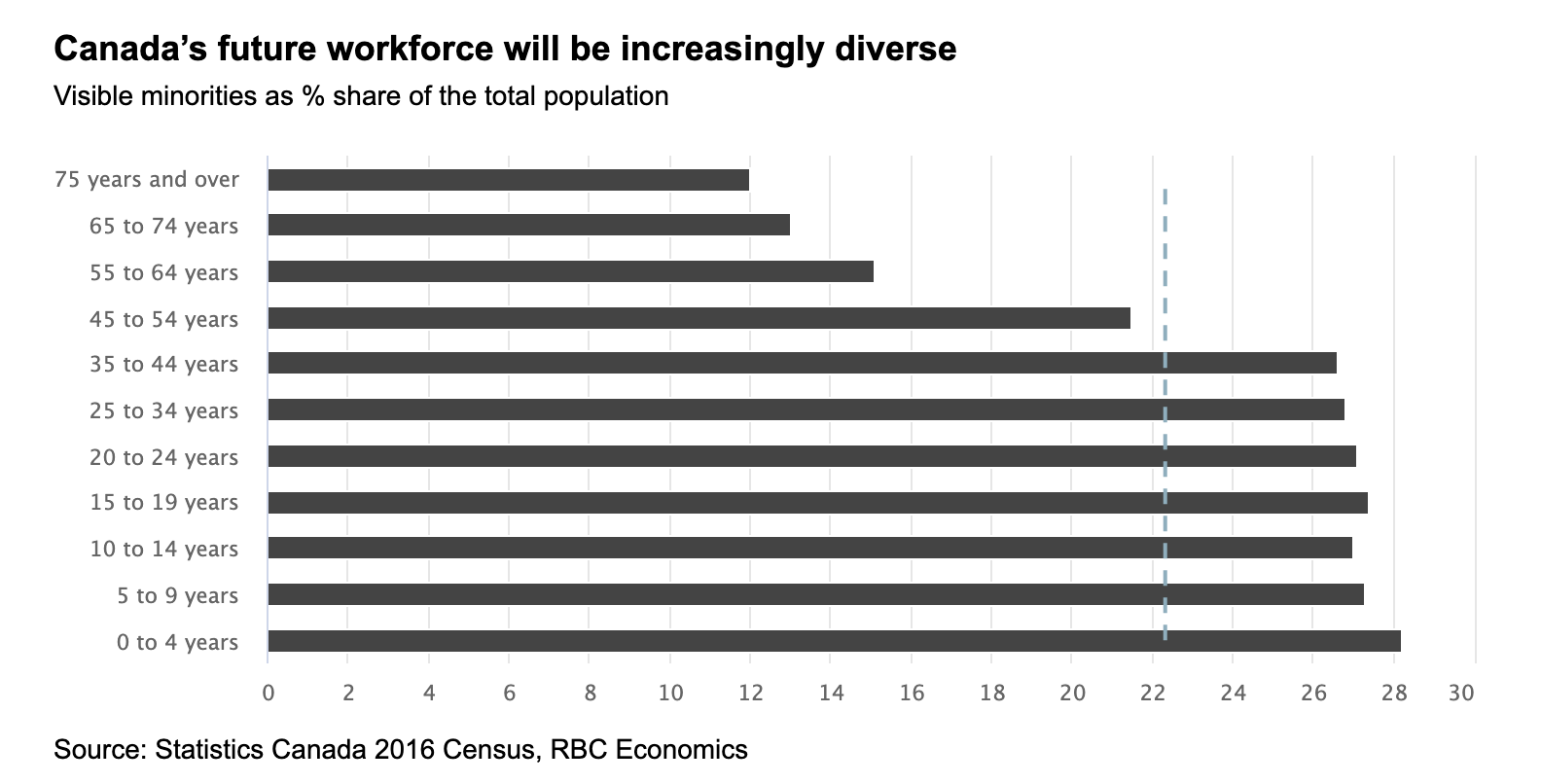

Canada’s future labour force will be increasingly diverse. Over a million visible minority youth will hit working age over the next decade. Immigration is also accounting for a rising share of expected Canadian population growth. In 2016, 22 percent of Canadians identified as a visible minority. By 2036, 34.7 percent to 39.9 percent of working Canadians will belong to the visible minority community, according to Statistics Canada. Improving labour market outcomes for these groups will require finding new ways to recognize, and ultimately reward, the credentials of recent immigrants.

Engaging workers at the margins will hedge against an aging workforce

Baby Boomers continue to retire in ever-greater numbers, putting a strain on labour supply. Difficulty finding workers has long been a problem for Canadian companies, and will continue to be post-pandemic. Amid such a pronounced demographic shift, it is imperative to attract new workers, but also to more effectively utilize the workers we have. The underutilized talent pool of visible minority Canadians can help bolster Canada’s ageing workforce. It can also give Canada a skills advantage since many of these workers are university educated.

We can rebuild a better, more inclusive Canadian labour market

As Canada rebuilds its economy, it has an opportunity to re-envision its labour market and make a deliberate effort to close gaps that have put many Canadians at a disadvantage. The challenge for policymakers will be to ensure that the right infrastructure is in place to recognize skills and credentials and to encourage dislocated female and visible minority workers to rejoin the labour force. For women, the issue is even more pronounced, given the overarching needs of balancing work, child/elder care and other domestic responsibilities.

The crisis has opened a unique opportunity for Canada to address these longstanding shortcomings in our job market. Failing to seize it, will mean missing out on a sizeable economic opportunity.

This report was originally published by RBC Thought Leadership

Rannella Billy-Ochieng’is an economist at RBC. She holds a Bachelor of Science (Honours) in Economics & Accounting from University of the West Indies, Master of Research in Money, and Banking & Finance from Lancaster University and a Master of Arts in Economics from the University of Guelph.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

In Quebec, financial planning services are provided by RBC Wealth Management Financial Services Inc. which is licensed as a financial services firm in that province. In the rest of Canada, financial planning services are available through RBC Dominion Securities Inc.