Gold has fascinated humanity since antiquity. Rare, dense, and indestructible, it has outlived empires, financial crises, and technological revolutions. A gold coin minted in Roman times still holds value today, while nearly all paper currencies created over the past two centuries have disappeared.

Since the beginning of the millennium, its price has risen nearly fifteenfold. And contrary to the popular belief that gold rises mainly during inflation or fear, we believe this long-term move is primarily a matter of supply and demand. The players involved are very different than most resources.

We will therefore explain why gold is rising, and what role it can play in your portfolios.

Extremely limited gold supply

Gold is extremely difficult to extract. A little over 200,000 tonnes have been mined throughout human history, the equivalent of a cube roughly 22 meters on each side.

Global production grows very slowly. It now sits around 3,600 tonnes per year, only slightly more than ten years ago.

Each additional ounce is increasingly expensive to produce. New deposits are deeper, more remote, or geopolitically riskier. Bringing a new mine into production often takes more than a decade. This explains why global output is not rising, even with prices much higher than twenty years ago.

Jewelry, savings and investment: private demand

Private demand is dominated by jewelry, about 2,000 tonnes per year, mainly in India and China. This demand is highly sensitive to price : strong when gold is cheap, weaker when it is expensive. Jewelry sales can even become a source of supply when prices spike.

Investors buy bars, coins and ETFs. This demand is relatively stable in the West but strong in Asia. In Japan, zero interest rates pushed households toward tangible assets. In China, the collapse of the real-estate market has caused a massive shift toward gold as a store of value.

When gold defined power

The other major component of demand today, and likely the most decisive, comes from central banks.

For centuries, gold was money, and it defined the financial strength of a state. The more gold a kingdom held, the more it could fund its armies, its wars, and its infrastructure.

Sixteenth-century Spain illustrates this perfectly: the first true global empire thanks to the gold and silver extracted from Latin America, yet it ultimately defaulted eight times in the 17th and 18th centuries. The huge inflow of precious metals pushed prices higher and created an illusion of wealth, masking the lack of taxation and productive investment, while wars continued to be financed through debt.

From the late 17th century onward, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom gradually established paper-money systems backed by gold, enabling them to finance major projects without relying solely on the metal. In the 19th century, the major European powers adopted the gold standard: their currencies were convertible into gold at a fixed rate, which reassured investors.

The system collapsed during World War I, when nations suspended gold convertibility, accumulated massive debts, and transferred a large portion of their gold to the United States to finance the war effort. At the end of World War II, the U.S. held nearly 80% of the world’s monetary gold.

In 1944, the Bretton Woods agreements established the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency, convertible into gold at 35 USD per ounce. Other nations pegged their currencies to the dollar.

But in the 1960s, U.S. deficits exploded due to the Vietnam War and domestic unrest. Europe and Japan accumulated trade surpluses and began demanding gold in exchange for their dollars, which explains why Germany and Italy are today the 2nd and 3rd largest official gold holders.

In 1971, Nixon ended Bretton Woods and suspended convertibility because the U.S. no longer had enough gold to back the number of dollars circulating worldwide. Currencies became freely floating, and for the next thirty years the Western world sold its gold. Canada even sold its entire 1,000-tonne reserve between 1980 and 2005, a unique case globally.

Power vs debt: the return of a historical pattern

According to historian Niall Ferguson, an empire reaches its peak when the interest on its debt exceeds its military spending. This happened to Rome, the Bourbons, the Habsburgs, Napoleonic France, and the United Kingdom in 1914.

The pattern always repeats: a rise in power funded through military strength, commerce and innovation, followed by debt accumulation, rising interest rates and expanding social commitments. When interest payments surpass military spending, decline begins.

The United States has now crossed this symbolic threshold: federal interest payments represent about 3.1% of GDP, compared with 2.9% for military spending. These figures are far from historical cases where interest absorbed half of public revenues, but the signal is clear: an increasing share of U.S. resources is now spent financing the past rather than military power and innovation.

Western central banks hold about 70% of their reserves in gold, while other countries hold officially only about 10%. For these countries, concentrating reserves in U.S. dollars has become risky. Diversification has become essential. In this context, gold is the only global reserve asset that is nobody’s liability, belongs to no political bloc, and can be stored or moved discreetly.

Central banks are buying massively

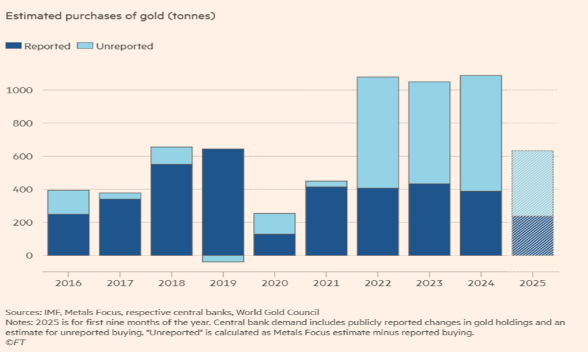

Today, central-bank gold purchases come mainly from non-Western countries, which are buying at a record pace. China is likely the largest buyer, although it intentionally obscures its transactions. It is estimated that less than half of its purchases — roughly 1,000 tonnes per year — are officially reported. Its holdings of U.S. Treasuries have dropped from 1.25 trillion USD to about 750 billion since 2010, even as U.S. debt surged, indicating that Beijing is actively reducing its dollar exposure.

Canada, which believed it was selling most of its gold to the United Kingdom, recently discovered that these purchases were being made by China through London-based intermediaries

Canada’s role and our positioning in gold

For Canadian investors, the environment is particularly favourable.

The country holds no official gold today, but it remains the world centre for gold-mining companies. About 51% of the global market capitalization of listed gold companies is in Canada, and roughly 40% of global mining financing flows through Canadian markets, even though the country represents only 3% of global equity markets.

We have held gold in portfolios for about fifteen years. Our approach is highly selective. We favour companies that gradually increase production or have credible expansion projects, rather than those relying solely on aging deposits. We favour stable jurisdictions and avoid high-risk regions such as parts of Africa, former Soviet republics or Turkey.

Unlike twenty years ago, the gold companies we hold are mature businesses generating solid cash flows, able to pay dividends and reinvest in new deposits without jeopardizing their balance sheets. They prioritize quality over quantity. Thanks to operational leverage, these companies tend to outperform physical gold when prices rise while reducing volatility in diversified portfolios.

Conclusion

No one can predict the short-term price of gold. Central banks may pause purchases temporarily, and markets may overreact. But over the long term, we believe gold will continue to play an important role.

For Canadian investors, this is a unique opportunity: to hold not only gold, but also high-quality gold-mining companies located in the country where they are most numerous and most robust.

RBC Dominion Securities Inc.* and Royal Bank of Canada are separate corporate entities, which are affiliated. *Member–Canadian Investor Protection Fund. RBC Dominion Securities Inc. is a member company of RBC Wealth Management, a business segment of Royal Bank of Canada. ® / ™ This information is not investment advice. The information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable at the time obtained but neither RBC Dominion Securities Inc. nor its employees, agents, or information suppliers can guarantee its accuracy or completeness. This report is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities. This report is furnished on the basis and understanding that neither RBC Dominion Securities Inc. nor its employees, agents, or information suppliers are to be under any responsibility or liability whatsoever in respect thereof.