The emergence of shale oil propelled the U.S. into an energy superpower and has been a primary source of oil supply growth over the last decade. Recently, the shale boom has slowed and contributed to the view that oil supply could struggle to meet demand in the years ahead. Are Canadian oil sands the solution?

Heavy oil takes greater effort to process into refined products than light oil. Oil Sand* is a mixture of bitumen, sand, clay, and water. Because it does not flow like conventional crude oil which is a liquid, it must be mined or heated underground before it can be processed. Bitumen can be extracted in two primary ways: mining and in situ.

Mining

About 20% of Canada’s oil sands are close enough to the surface to be mined. Large trucks and shovels extract the oil sands that are near the surface (approx. 130-200 ft deep). Hot water is used to separate the bitumen from the sand (extraction process). Bitumen is heated and sent to drums where excess carbon (in the form of petroleum coke) is removed.

Some heavy oil, and about half the bitumen produced from the oil sands, is upgraded to create synthetic crude oil. Synthetic oil is usually low in sulphur and contains no residue (very heavy components).

In Situ

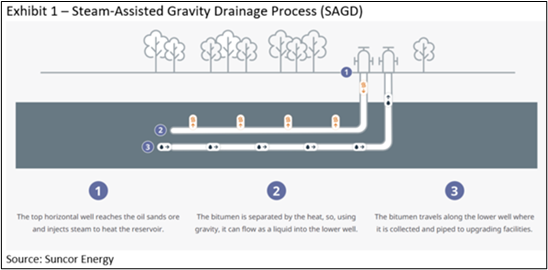

“In situ” means “in place,” because bitumen is separated from the sand below ground, right in the deposit itself. Approximately 80% of Canada’s oil sands are too deep to mine using the truck and shovel technique and must be tapped using in situ production, a three-part process to drill, inject steam and extract bitumen to the surface.

The injection well is drilled vertically into the deposit, then turned 90 degrees and drilled horizontally. A second well, known as the production well, is drilled deeper than the first, paralleling the horizontal portion of the first well. Steam is injected into the deposit through the upper well. Heated bitumen begins to move by gravity down toward the second well. Pumps in the second well draw the bitumen into the well and up to the surface.

U.S. Tight Oil

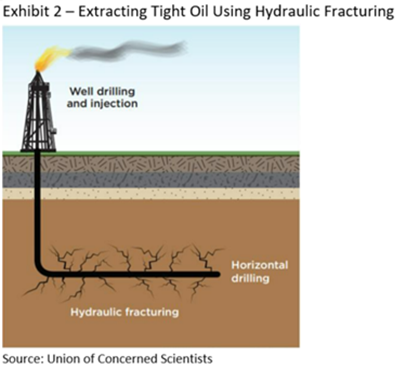

US tight oil (sometimes called “shale oil”) and the use of hydraulic fracturing in horizontal wells has made the United States a major crude oil exporter in recent years.

Hydraulic fracturing, also known as fracking, is a process used to recover oil and natural gas trapped in non-porous or “tight” rock formations such as shale. In the most simplistic terms, large volumes of water, sand, and chemicals are pumped into underground rock at high pressure until it fractures and frees the trapped oil and gas.

The economics differ greatly between oil sands and shale. To start with, the upfront capital costs in the oil sands are higher than that of shale. Once built, the cost is considered to be "sunk" and thus previously built oil sands assets are more profitable and generate more free cash flow. This cash can be returned to shareholders, as many oil companies are doing today.

A metric commonly quoted is an oil field's decline rate - the speed at which production volumes decay over time. For oil sands it is low, around 10% per year, whereas for shale it can be up to 40%. This means shale assets have a shorter reserve life and are more reliant on "treadmill-like" exploration activity to sustain (let alone grow) production.

With elevated ESG scrutiny, some investors are now demanding cash to be returned to...

ESG- Environmental, Social and Governance. A term used to represent an organization’s corporate financial interests that focus mainly on sustainable and ethical impacts.

...stakeholders instead of reinvested back into the business. Hence we are seeing record debt repayment, dividends, and buybacks while capital investments lag. This makes it difficult for energy producers to grow their businesses. Global oil companies have paid down an estimated $209bn of debt between 2020 and 2022. Over the same period, they have returned to shareholders (through dividends, special dividends and share repurchases) another $206bn. This has been supported by very healthy free cash flow generation in 2021 and especially 2022.

While free cash flow, for the group, is expected to decline by -35% in 2023 (on lower energy prices, cost inflation and arguably less demand due to a slowing economy), they are expected to keep shareholder returns flat at $206bn, while paying off another $52bn in debt. The focus on debt repayment has significantly strengthened balance sheets across the industry, positioning them well for potentially lower oil.

The political environment in Canada is averse to further oil sands development. Various groups have intentionally or unintentionally impeded industry growth via regulation, taxation, land rights claims, environmental rules, pipeline opposition, export infrastructure, etc. In contrast, policies and attitudes in the U.S. are far more favorable. This perceived friendliness has important impacts on where oil executives choose to invest. - Brad

Thank you to Jackie Au and Sunny Singh, from RBC's Portfolio Advisory Group, for sharing research and content with me for my blog.