For subsequent generations of inflation watchers, central banks’ success in keeping inflation near or below the 2% target has made today’s rates look shocking. But is the current pandemic-related jump in prices really the beginning of a new era of inflation? Just as the COVID-19 crisis was unlike what we’ve experienced before, a massive savings trove, the rapid rate of recovery and the contours of the recovery are making this inflationary experience unique.

In this report, we identify the current factors at play. Some of these will dissipate in 2022 but others will remain and potentially accelerate. Containing inflation expectations will require a reduction in policy support—both fiscal and monetary—combined with an easing in production disruptions as supply catches up to demand. It’s a tall order.

While the global economic recovery has played out unevenly across countries, the rise in inflation rates have been nearly universal. Some of the pressures driving the surge—base effects, higher commodity prices, policy stimulus and increasing input costs—will ease in the months ahead. But consumer demand will remain very strong, due in part to exceptionally high household savings accumulated in most advanced economies during the crisis and as labour shortages put upward pressure on wages. Meantime, central banks are signaling a willingness to keep rates low to ensure economies fully recover pandemic-related losses. Against this backdrop, inflationary tailwinds will persist.

For the Bank of Canada, the challenge this presents is significant. Like the U.S., U.K. and the Euro-area, Canada’s inflation rate accelerated sharply in 2021—rising at its fastest pace in over 18 years in October. The brisk increase, and the prospect that Canada’s inflation rate will remain well above the Bank of Canada’s target band for several more months, will intensify pressure on the bank to balance maintaining its inflation-fighting credibility with facilitating a full, inclusive economic recovery. In the near term, one legacy of the pandemic will be higher inflation. We expect inflation rates to remain above pre-pandemic levels next year before easing back toward target in 2023. Below, we offer our assessment of how inflation will evolve.

Inflation math: How we got here

Some of the surge in the inflation rate reflects a return to more normal pricing after dramatic declines a year ago, when the pandemic delivered a significant economic blow. Indeed, inflation growth over a 2 year period is less striking than the one-year inflation rate often quoted. By our calculation, those ‘base-effects’ alone accounted for about 2 percentage points of the increase in the inflation rate in 2021. Their impact will fall toward zero in 2022.

Reopening challenges will linger

One of the main differences between the current recovery and previous episodes is that goods prices, which dropped in the early days of the pandemic, accelerated abruptly in 2021. Supply chain disruptions curtailed production while demand surged propped up by government supports that fueled household purchasing power amid fewer opportunities to spend on services.

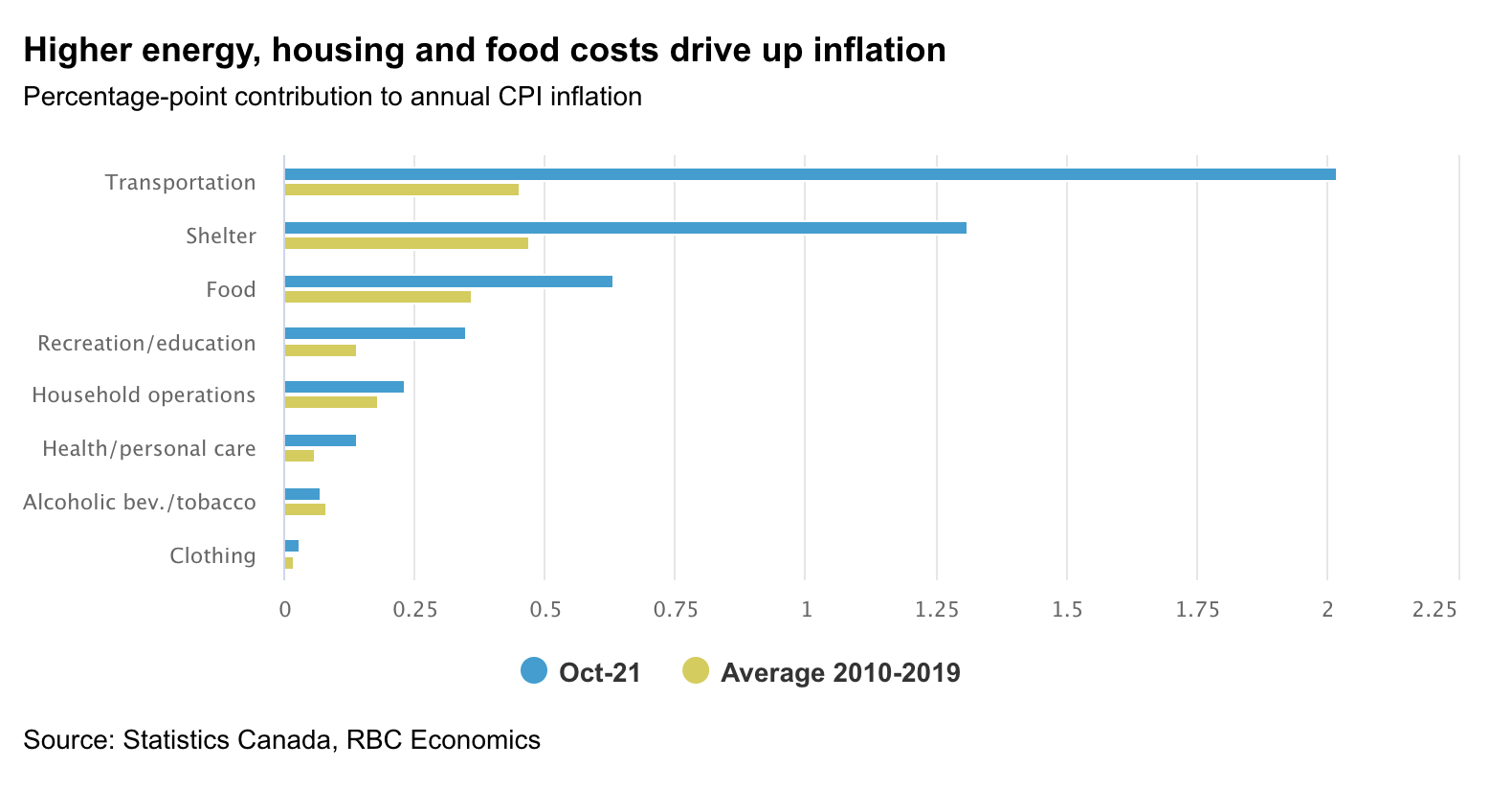

The services sector, where inflation usually runs faster, stayed in neutral early in 2021 but picked up sharply over the summer as the economy reopened. Shelter costs have dominated those increases, reflecting Canada’s exceptionally tight housing markets. The cost of ‘other owned accommodation’ (which includes realtor/broker fees) and replacement cost of housing are both heavily influenced by house price appreciation. These factors alone have accounted for more than a third of the increase in the consumer price index above and beyond pre-pandemic levels.

But demand for other services, especially those that require close contact, has also continued to firm. The result is a twin set of pressures: strong goods price inflation and accelerating services price inflation. On the goods side, price increases reflect the rising costs of inputs due to higher commodity prices and costs associated with transportation bottlenecks. The surge in energy prices accounted for about a third of October’s 4.7% annual increase in inflation—though this contribution is expected to fade as oil prices stabilize over the year ahead.

How long other factors will remain in play, like disruptions to supply chains, is more difficult to assess. In recent months, bottlenecks have led shortages of autos, household appliances and building materials, resulting in upward pressure on prices. And container shipping costs are still running 7 or 8 times above pre-pandemic levels. Supply chain snarls are likely to ease as vaccinations become readily available to supplier countries. And RBCCM analysts expect that the shipping backlog to be cleared by May 2022. But the exact timing remains highly uncertain and residual effects could persist into the second half of 2022.

For housing, supply issues are likely to persist in the near term though strong construction and cooler expected demand should bring markets closer to balance by the second half of 2022, easing pressure on shelter costs.

Too much money chasing too few goods

Both governments and the Bank of Canada have pulled back on aggressive support measures that were designed to help the economy through the crisis. However interest rates remain historically low and a significant amount of income supports for consumers and businesses landed on their balance sheets. As a result, a record level of spending power could be unleashed in the economy in 2022. Businesses are sitting on higher-than-normal levels of liquid assets and households have amassed $280 billion in excess savings. By our calculation, each 10% of households’ saving stockpile that is spent equals about 1 percent of GDP (The Great Canadian Savings Puzzle). With the economy expected to run up against its capacity limits around the middle of 2022, a deluge of spending would open the door to even more pressure on prices.

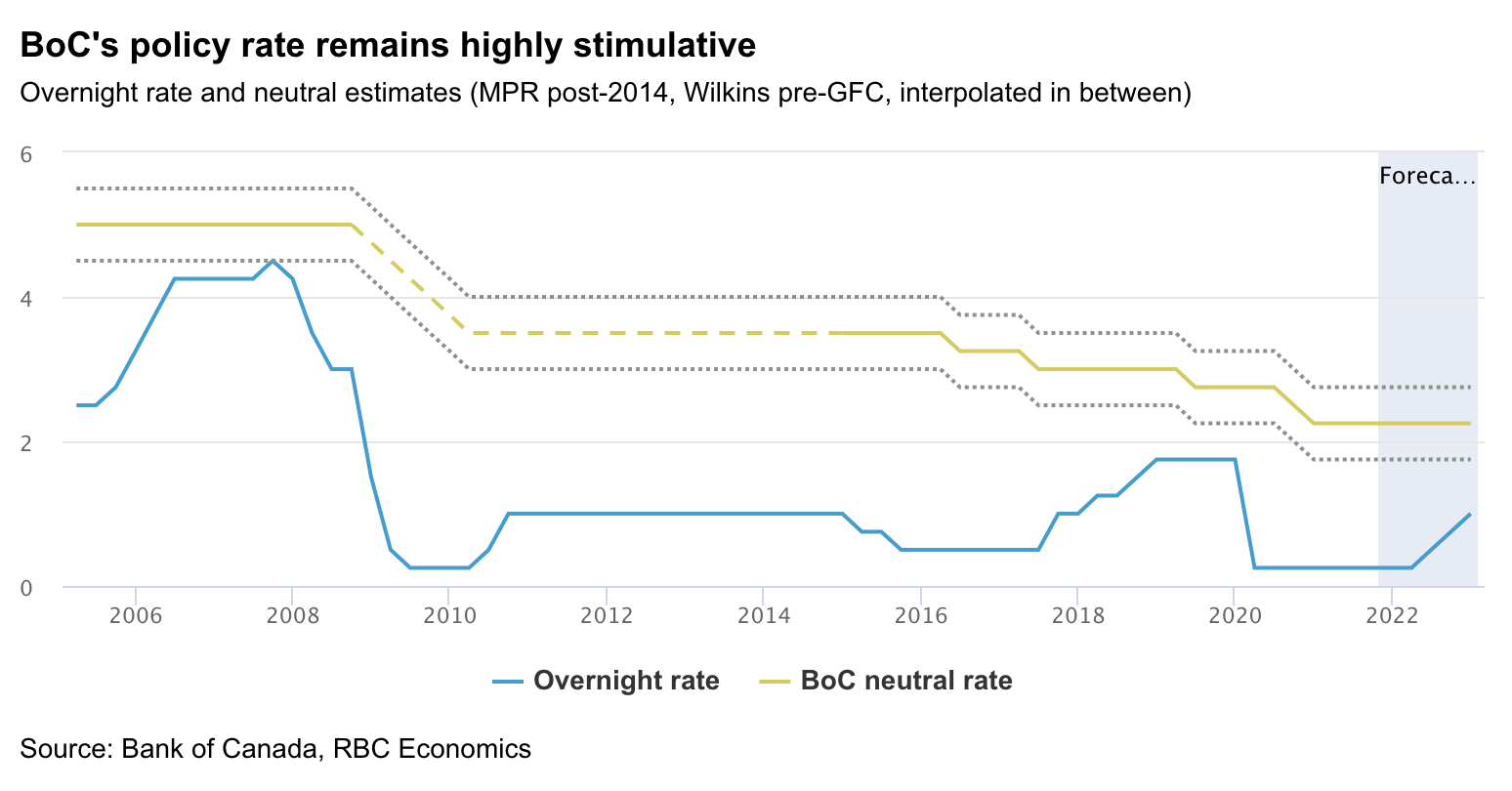

The Bank of Canada’s position is that the factors associated with the reopening of the economy will fade and excess slack will limit price increases as 2022 progresses. However unlike previous cycles, the economic recovery to-date has been relatively rapid, and household incomes actually rose sharply through the recession despite weaker labour markets with government support payments filling in for lost wages.The BoC has been vocal about the need for a fulsome, inclusive recovery but firming price growth has complicated matters and the central bank is now hinting that interest rates will have to rise. But even with our forecast that the policy rate will rise by 75bps next year, it will remain below the bank’s estimate of neutral meaning policy accommodation will remain.

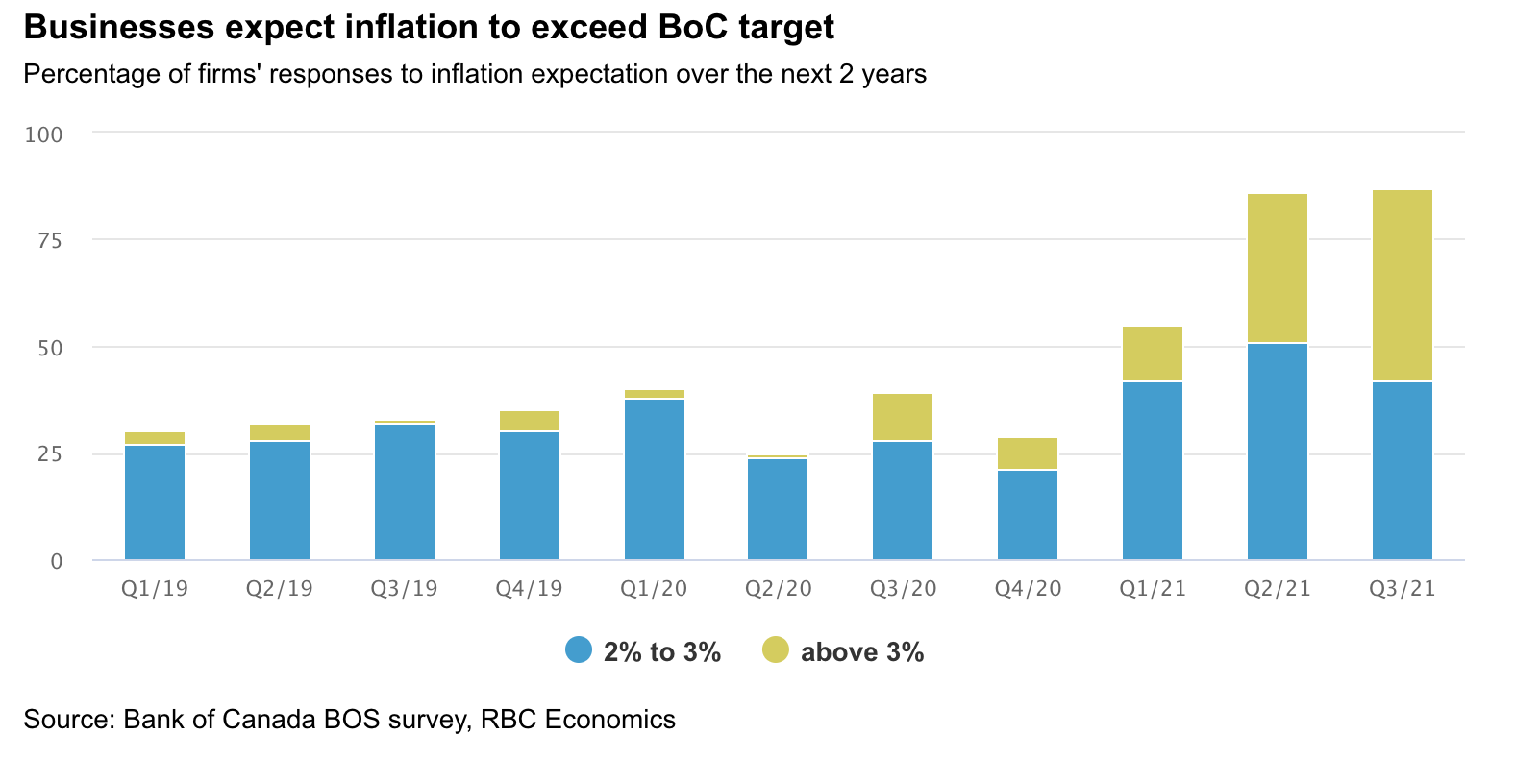

As central banks appear willing to tolerate a little more inflation to let the economy recover more fully, market-based inflation expectations have drifted higher. Survey data (Bank of Canada) shows 45% of businesses expect prices to rise at an average 3% pace over the next two years with small and medium-sized business expecting price increases to average 3.7% over next year.

The next pressure point: wage increases in the pipeline

Canadian employment is back to its pre-pandemic level and demand for labour remains very strong. In August, job vacancies stood at an all-time high at 871,000 or 5.2% of all jobs. Filling these positions won’t be easy, given the 2020 drop in immigration and the mismatch between the jobs that are available and workers willing to take them. A recent survey by the BOC showed 20% of workers said they expect to voluntarily leave their jobs over next year and almost half are confident they’d find a job in three months if they lost their position. Although wage increases have so far remained stable, pressures are building, especially in industries that face severe shortages. Businesses are already anticipating that the combination of higher input costs and wages will result in higher than usual inflation. The longer these expectations remain, the greater the likelihood they will materialize.

Today’s high inflation rates are likely to linger for most of 2022 but there are good reasons to expect that like the shock created by COVID-19, pressures will ease over time. Likely, this will require higher interest rates, lower government spending and a healing in the global economy that sets Canada back on a more sustainable growth path.

As Deputy Chief Economist, Dawn contributes to the macroeconomic and interest rate forecasts for Canada and the U.S. Before joining RBC, Dawn worked as a reporter for Bloomberg Financial News in Toronto covering the Canadian bond and currency markets. She also spent ten years as the Canadian bond market strategist for a major U.S. bank.