Almost half a million Canadian women who lost their jobs during the pandemic hadn’t returned to work as of January. More than 200,000 had slipped into the ranks of the long-term unemployed, a threefold increase over last year.

Before the crisis, these women held a wide variety of jobs, but there was a common thread. Many worked, for modest pay, in the low-skilled service jobs that helped keep the broader Canadian economy humming along. They may have lacked the economic clout of some other Canadian workers, but they were highly visible, in food courts, salons, pubs and elsewhere—places that didn’t allow for safe physical distancing when the pandemic hit. Because women represented the majority in industries most affected by virus-containment measures, they bore the brunt of the job losses.

Widespread vaccinations will bring back many service jobs. But firms have repositioned themselves to require fewer workers. And the year-long pandemic may have cemented new consumer habits around online shopping, at-home workouts and other digitally enabled activities.

In this way, the pandemic accelerated structural economic changes that were in motion pre-COVID. Canadian women were already at higher risk of disruption because they held more than half of the 35% of Canadian jobs susceptible to automation. The COVID crisis made them even more vulnerable, by forcing many firms to adopt contactless and other digital technologies far sooner than they might have otherwise.

Post-COVID, the work future for these Canadian women looks uncertain. This poses a challenge for Canadian policymakers and business leaders—to retrain the most affected workers for new ways of working in rapidly changing industries, or to help them transition to new sectors. Enabling this process won’t only benefit the displaced workers; ultimately, Canada’s overall economic health depends on the broadest possible recovery.

Long-term joblessness carries greater risk of skills erosion

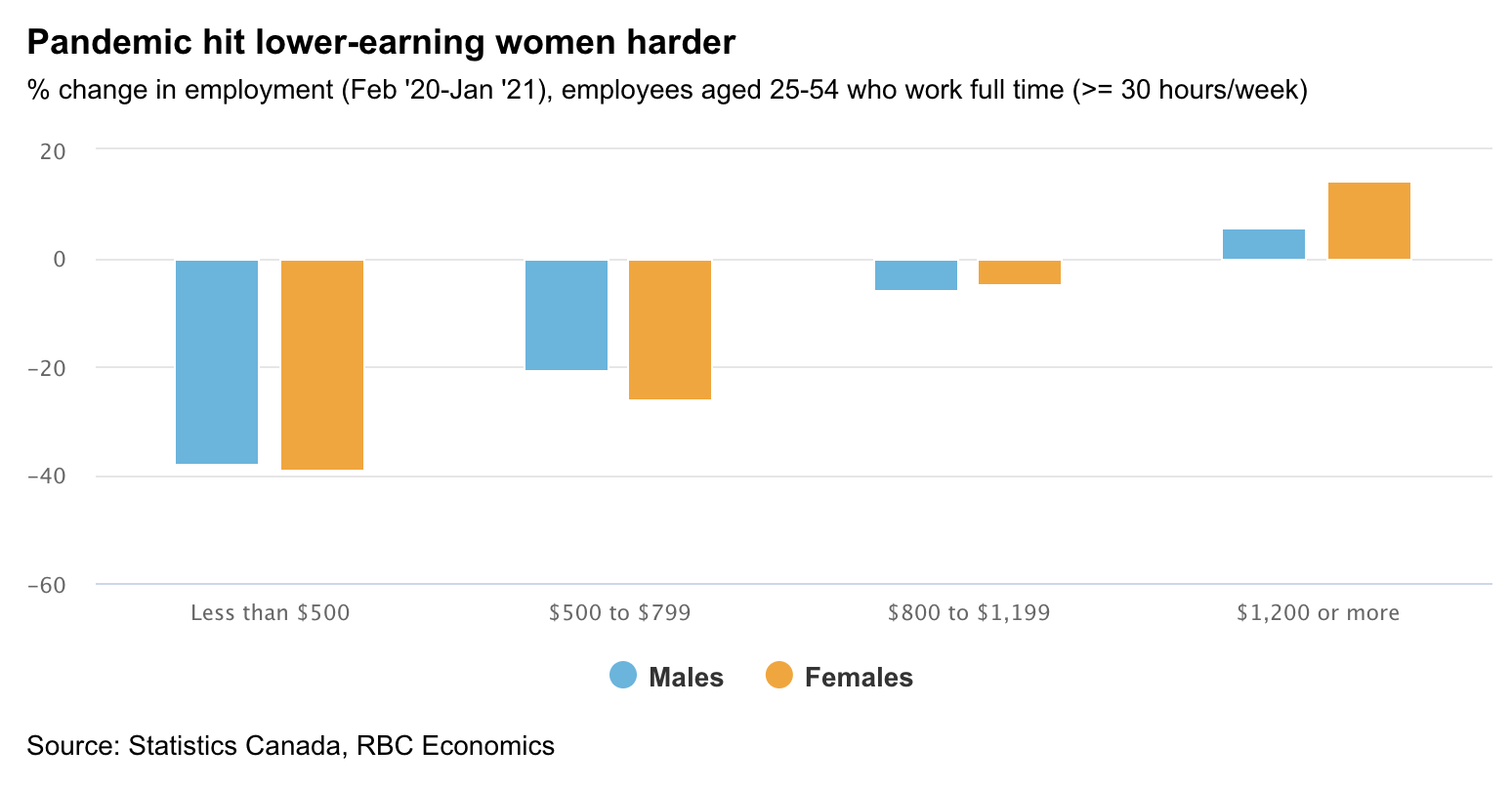

Employment among women in Canada who earned less than $800 a week has fallen almost 30%. For men in the same wage brackets, the drop is 24%.

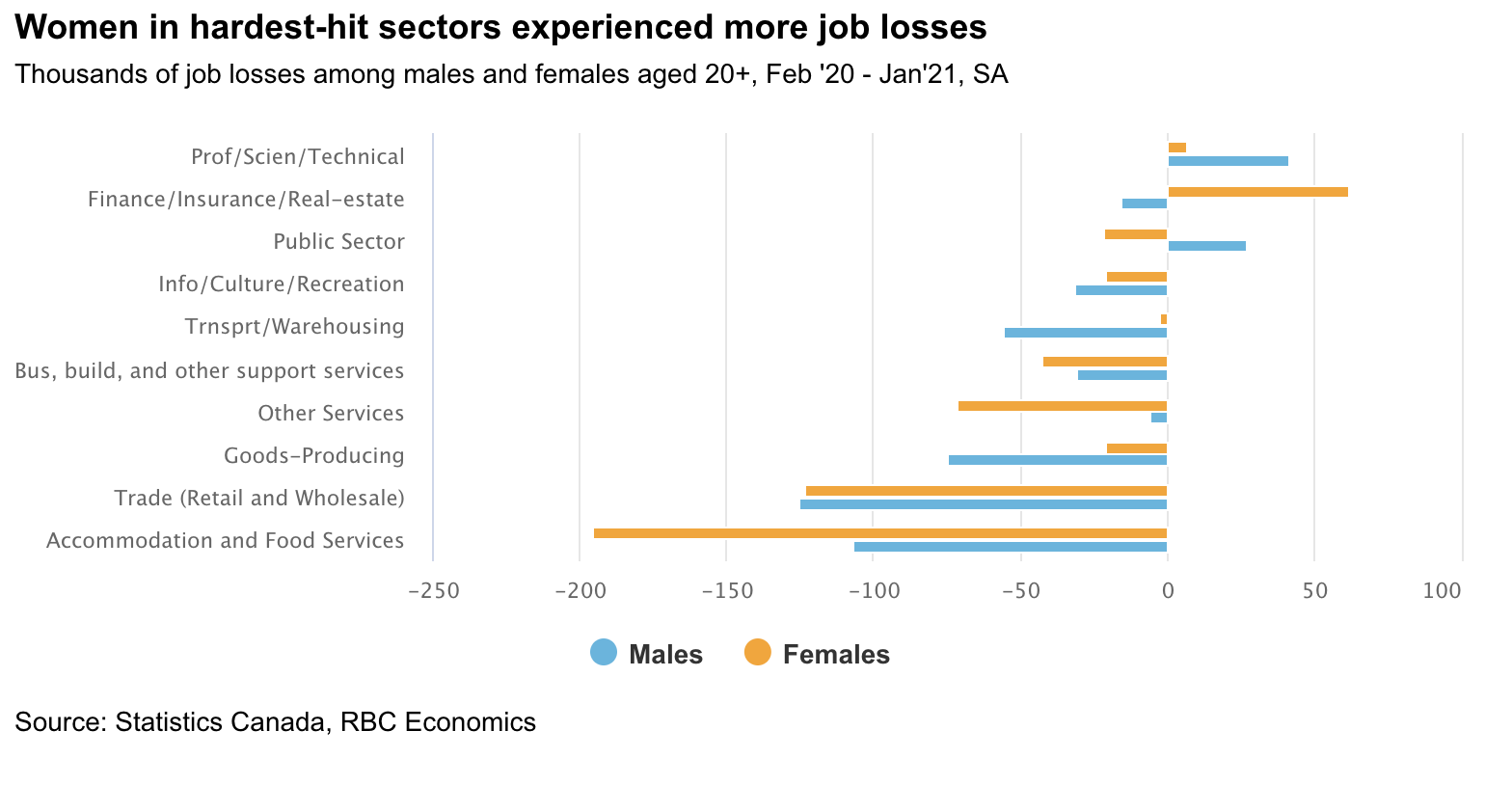

Women made up more than half of those employed in the sectors—hospitality and retail—that were most affected by virus-containment measures. They’ve absorbed 65% of the job losses in accommodation and food services, the hardest-hit indusrty. Men too saw early-pandemic job losses, in lower-contact industries like manufacturing and construction, but returned to work quickly.

It isn’t clear when workers in high-contact sectors will be able to return to work in full force, if ever—a situation that disproportionately affects women. Some businesses have closed. Others won’t rehire until lockdown measures and travel restrictions are fully lifted. Others have moved to contactless modes of service, requiring fewer staff.

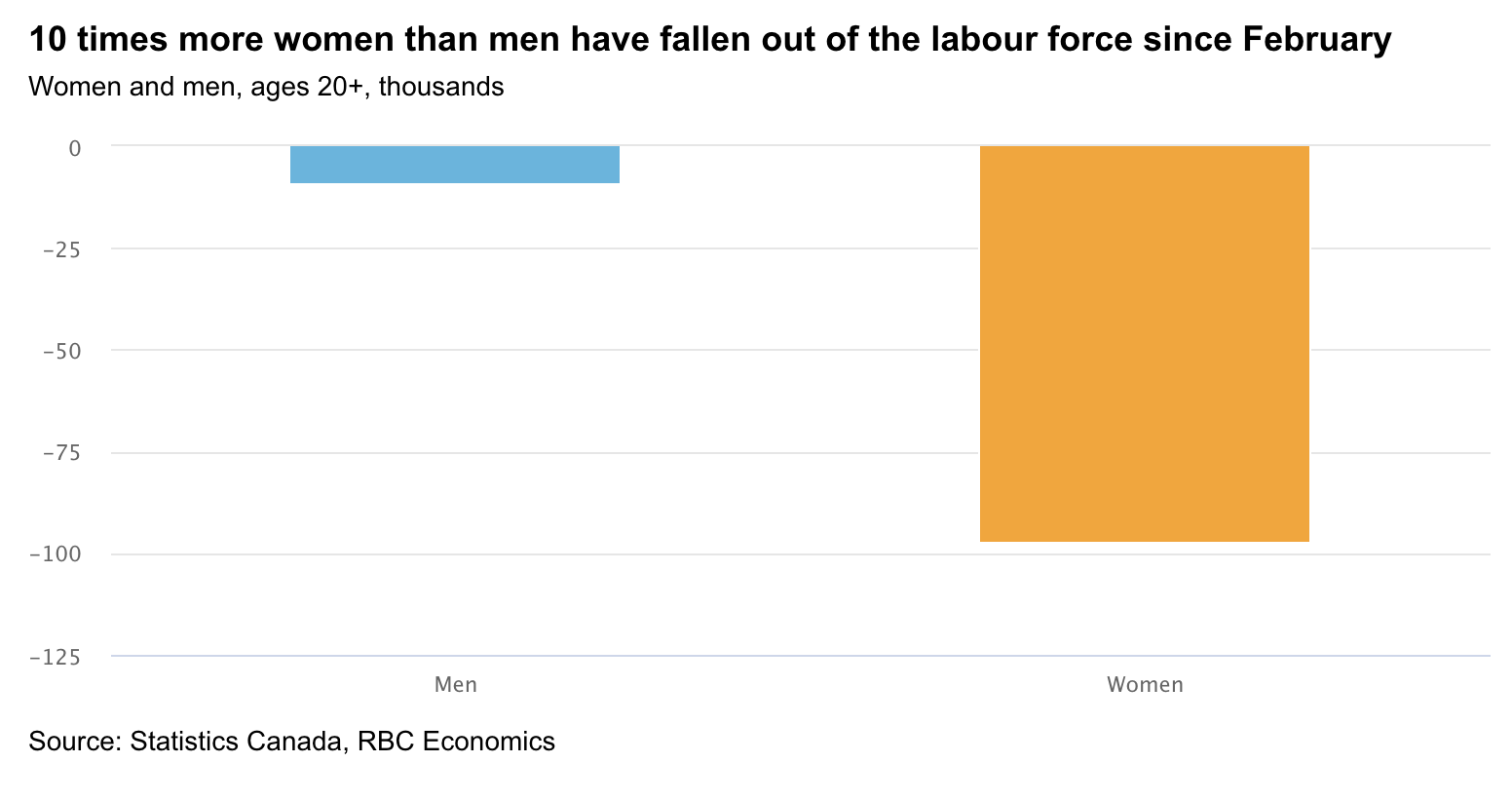

These developments set up many Canadians—predominantly women—for an extended period of joblessness. Almost 100,000 women aged 20-plus have exited the labour market entirely, compared with fewer than 10,000 men.

The longer these women are out of the labour force, the greater the risk of skills erosion, which could potentially hamper their ability to get rehired or to transition to different roles as the economy evolves.

Training and reskilling programs will be key to an inclusive recovery

Emergency-relief measures, including income supports and wage subsidies for businesses, offered a lifeline to workers displaced by the pandemic. But these programs will eventually be unwound, making the challenge of helping those who were permanently disrupted an urgent one.

A sizable number of Canadian women are at risk of the skills atrophy that comes with long-term unemployment. What can be done to improve labour-market outcomes for the lower-wage women, the immigrant women and others we’ve focused on in this report?

The federal government has allocated $1.5 billion for the provinces to support training and reskilling programs. Some provinces have already set up programs to help transition workers out of industries that have been most heavily impacted. The federally-funded Future Skills Centre is also working with employers to develop sector-focused skills initiatives for affected workers. Creating accessible and targeted training programs will be key to get workers back into the labour market.

The pandemic highlighted the value of digital skills in every sector. It’s clear that even workers in non-tech businesses like restaurants and apparel retailing will need to have the skills to handle remote booking and digital sales. Women in lower-skilled service jobs face a potentially longer and more arduous path to re-skilling. Ensuring that every youth graduating from high school has digital literacy will be critical. Those already in the labour force will need retraining assistance, from government and employers.

More options for affordable childcare would also help many lower-earning mothers get back to work. But it’s no solution if they don’t have jobs to return to.

As Bank of Canada Governor Tiff Macklem said in a February speech, we all have responsibility for getting more Canadians back to work and managing the forces of automation and digitalization. The greater the number of people who participate in Canada’s recovery, the stronger our economy will be when we emerge from the crisis.

Appendix: Underlying Data

Which women were hit hardest? Youth, visible minorities, newcomers… and many moms

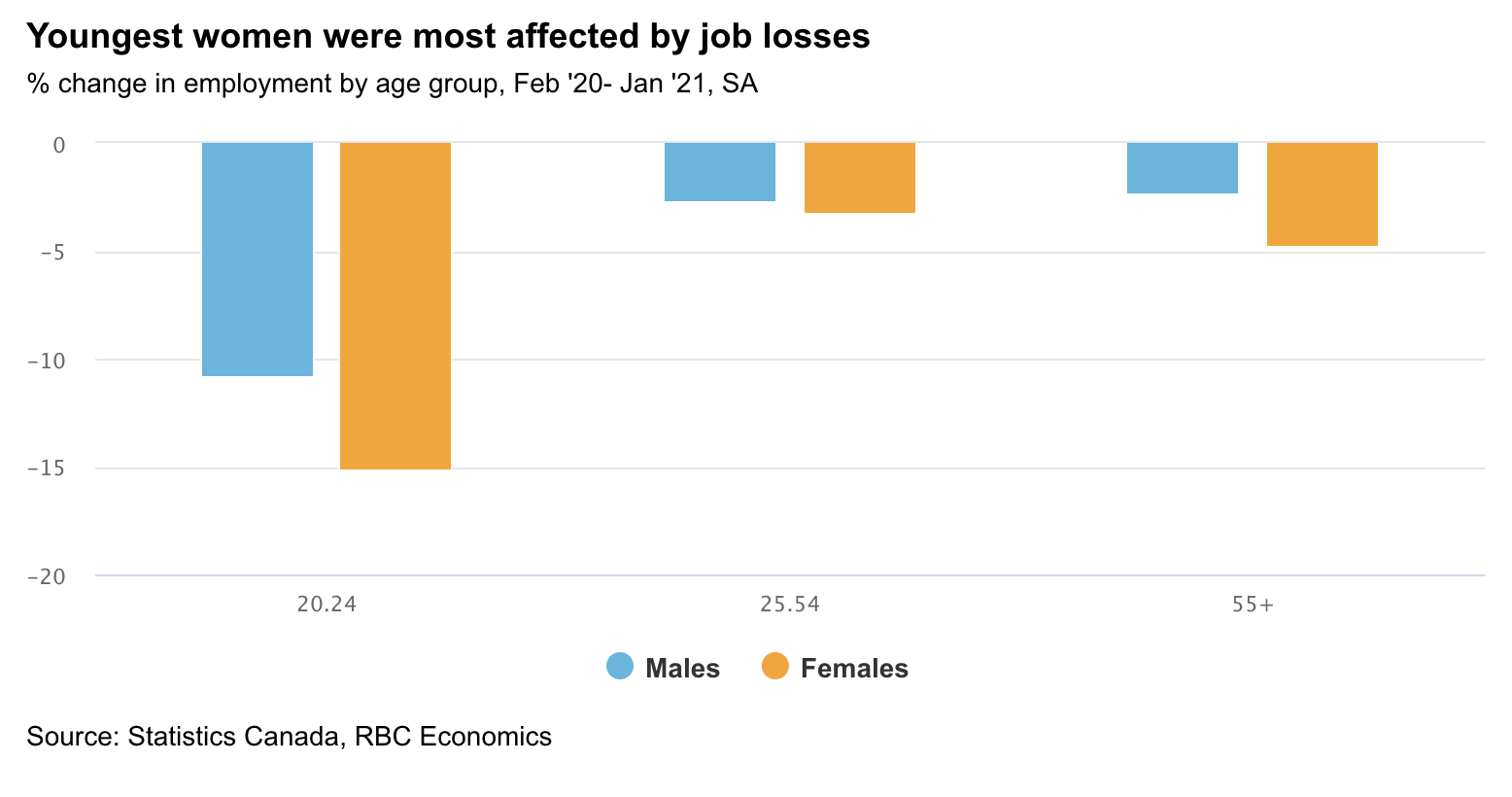

- Gen-Z women make up 2.5% of the Canadian labour force, but account for 17% of the total decline in employment during the pandemic.

- In January, the jobless rate unemployment rate for women aged 20-24 was more than 6 percentage points higher than its peak in the 2008-2009 recession.

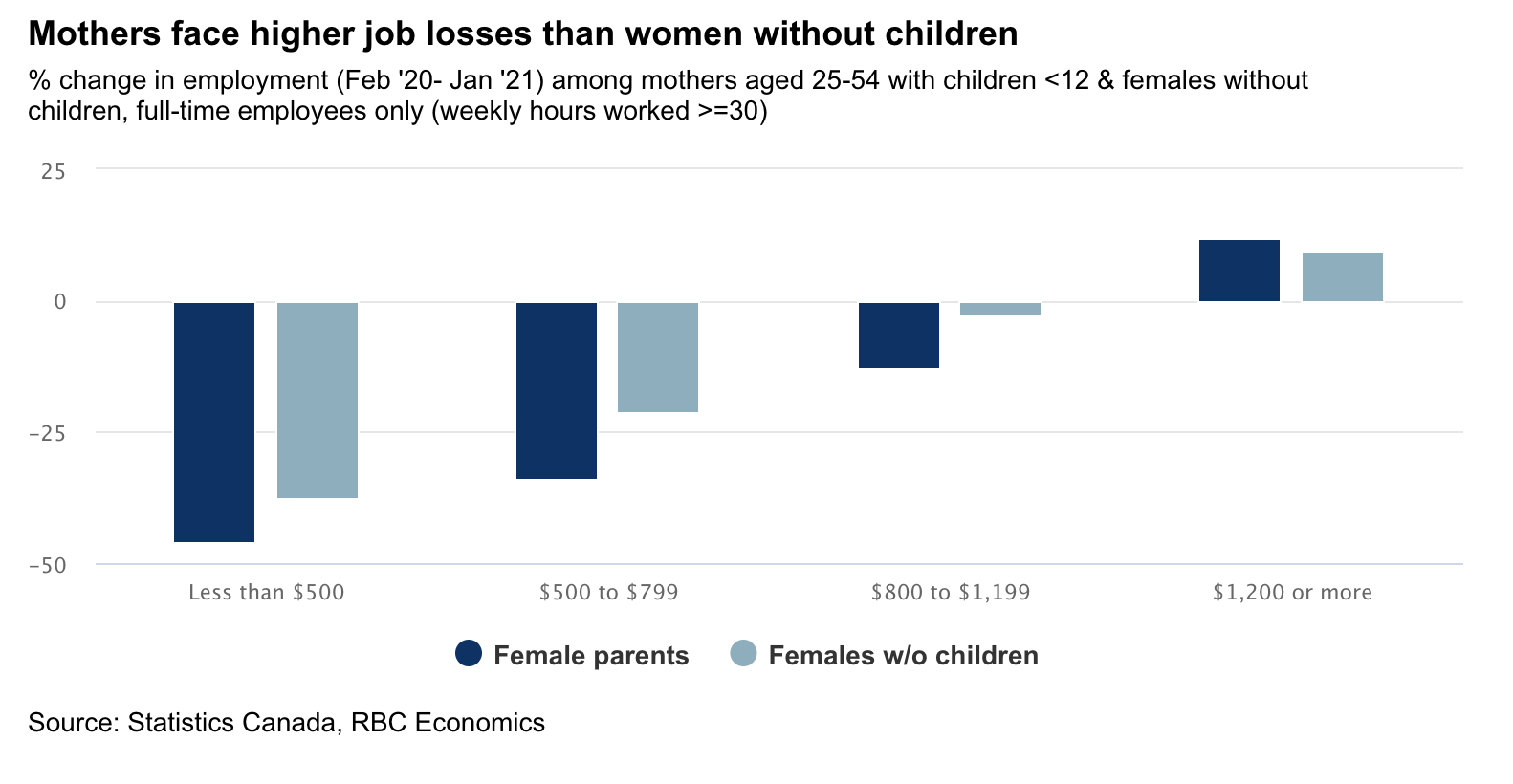

- Women have shouldered a heavier burden when the pandemic added homeschooling to their load. Around 60% of women with children under 12 earn less than $1,200 per week, and these women accounted for all of the job losses borne by prime-aged mothers.

- In the last year, 12 times as many mothers as fathers left their jobs to care for toddlers or school-aged children.

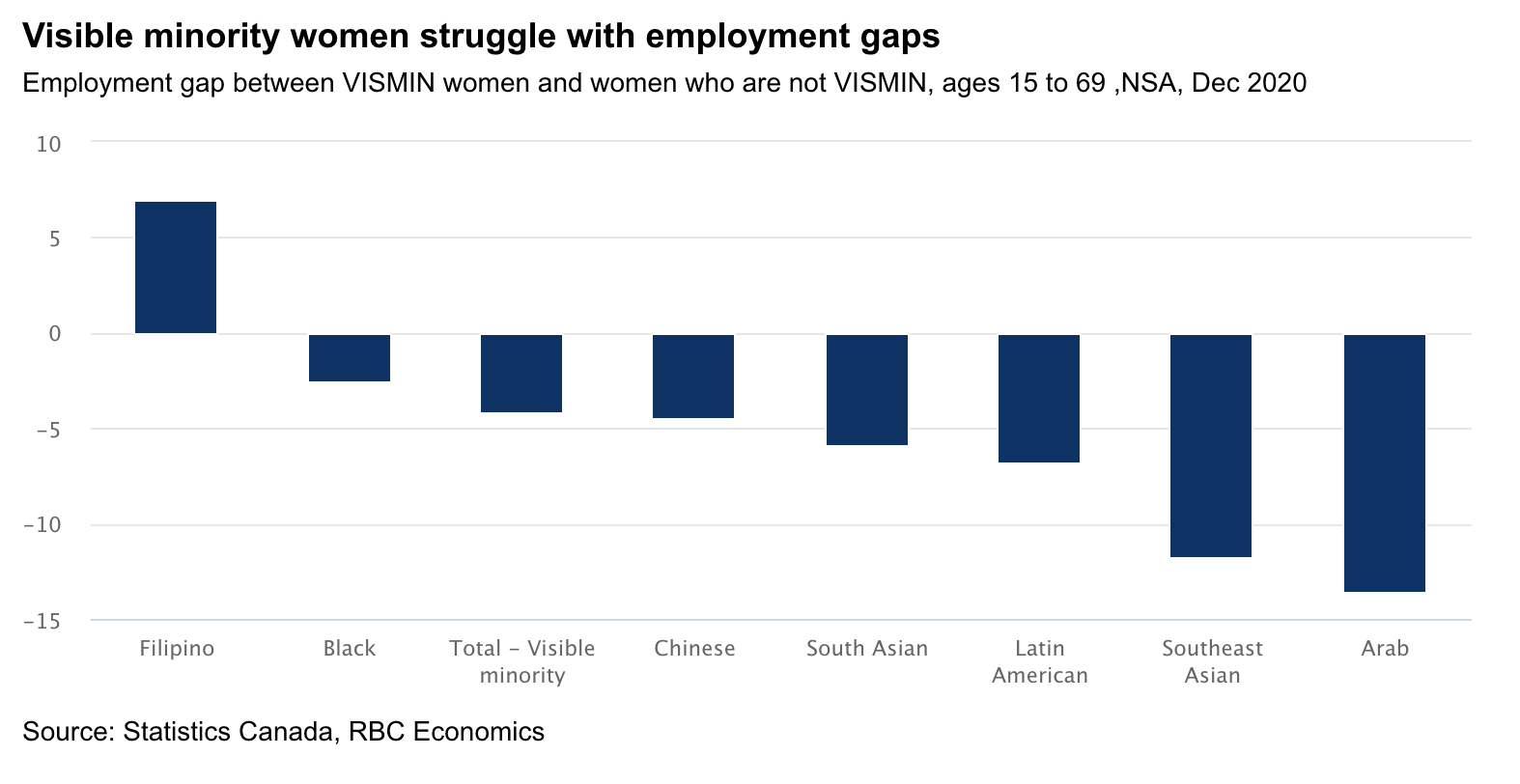

- Jobless rates among visible minority women have been higher. Many still face double-digit unemployment rates, compared with a jobless rate of 9.7% for women overall.

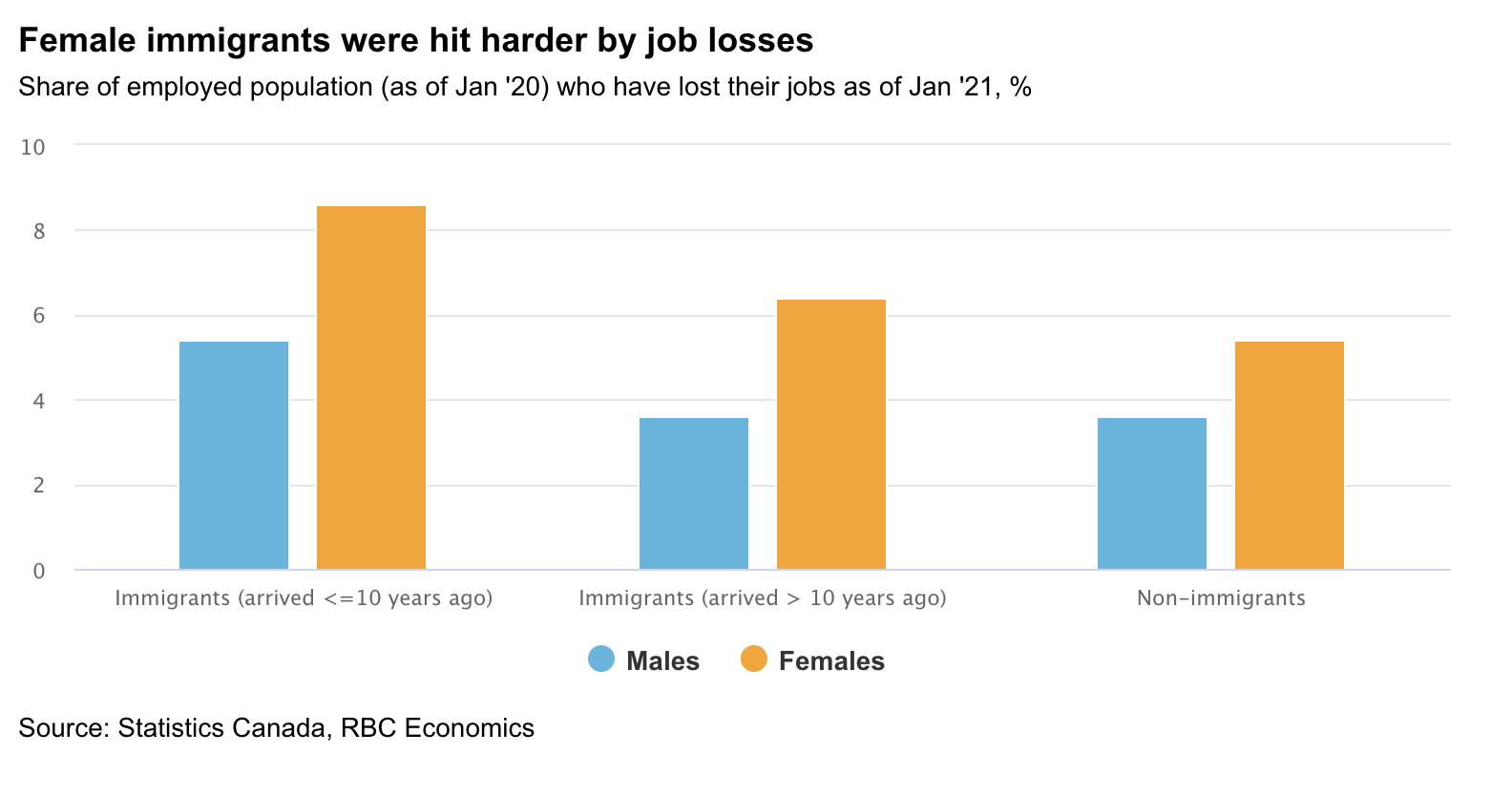

- Women who’d arrived in Canada within the last decade were more likely to lose their jobs, and 8.6% of them remain out of work.

- Immigrant women with children 12 and under experienced more than double the decline in employment (in percentage terms) of Canadian-born mothers.

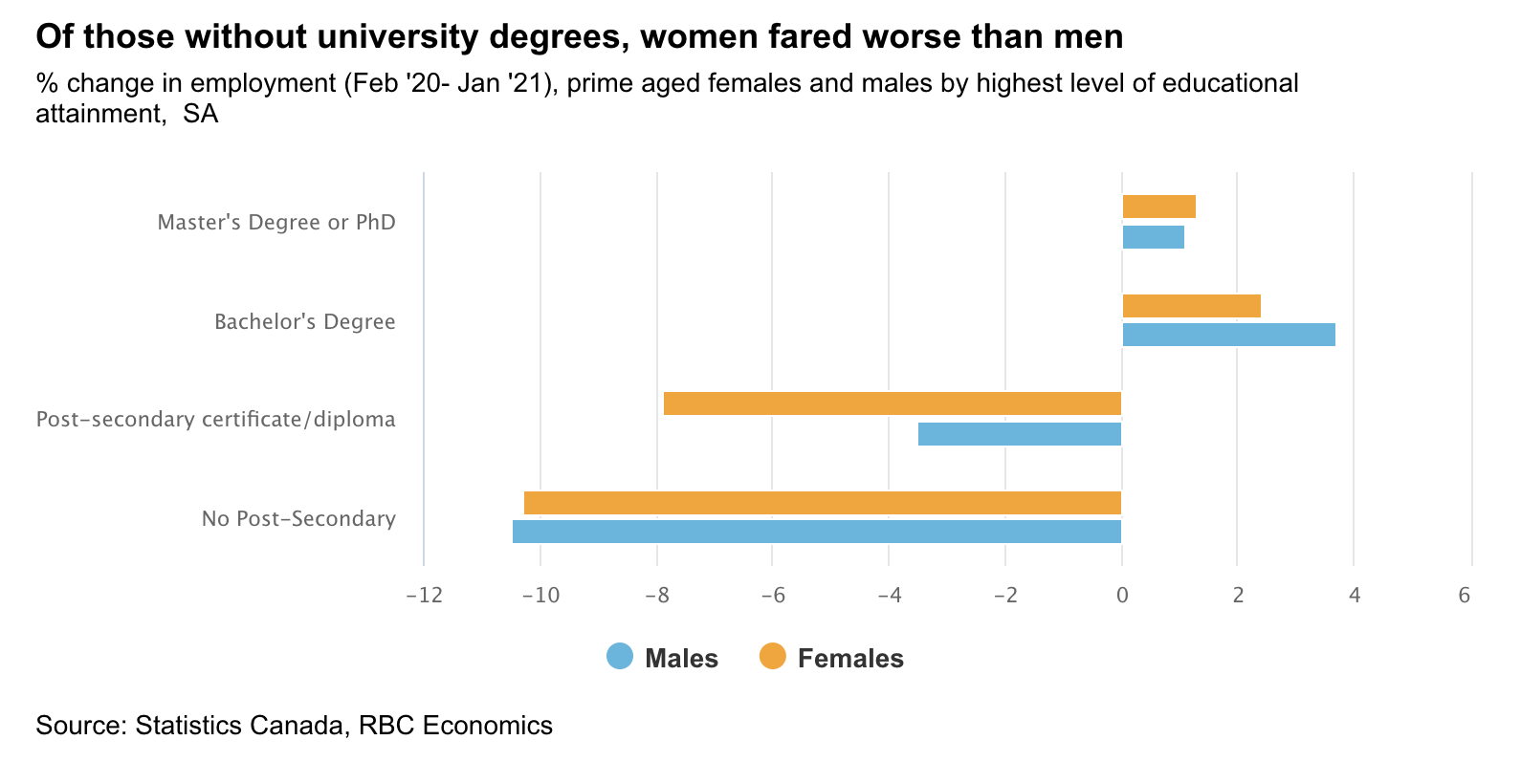

- Men and women without post-secondary education faced similar job losses, posting declines of 10.5% and 10.3%, respectively. But men with college education lost fewer jobs, and those with Bachelor’s degrees saw more job gains than their female peers.

- Even a university education did not safeguard female immigrants to the extent it did Canadian-born women. Female immigrants who’d been in Canada less than a decade and had a Bachelor’s degree lost jobs overall, while their Canadian-born peers recorded job gains.

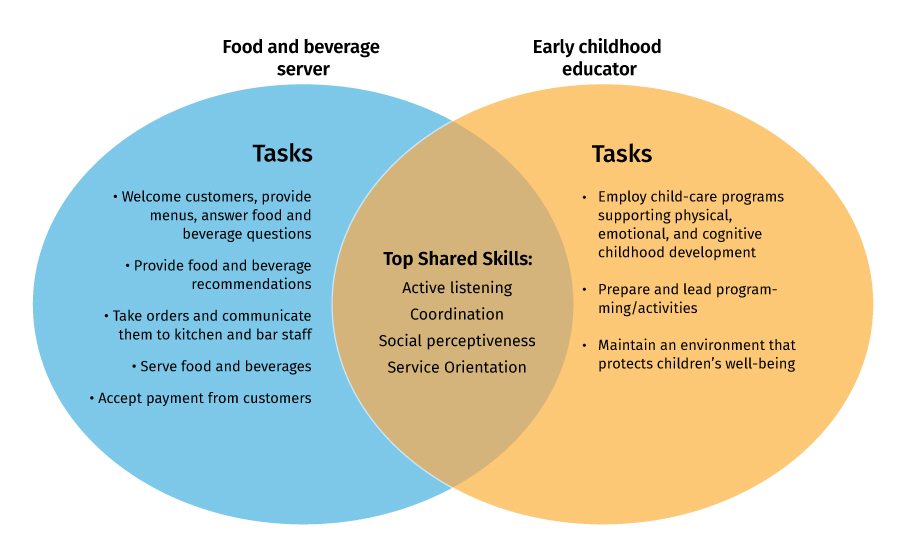

About 89,000 women worked in the Canadian food service and beverage sector in the fourth quarter of 2020, down 33% from the first quarter. Even before COVID, these occupations were expected to come under pressure from the forces of automation. However, workers in the sector have many skills that are very useful in other occupations, especially education and healthcare. Should food and beverage servers opt for a career transition, they possess many of the skills sought among early childhood educators, which are likely to be in demand. Both require active listening, coordination, service orientation, social perceptiveness, and speaking. Of course, any career shift will require some retraining; early childhood educators typically need at least a two-year college diploma.

Download report PDF

As RBC’s Deputy Chief Economist, Dawn Desjardins contributes to the macroeconomic and interest rate forecasts for Canada and the U.S. Before joining RBC, Dawn worked as a reporter for Bloomberg Financial News in Toronto covering the Canadian bond and currency markets. She also spent ten years as the Canadian bond market strategist for a major U.S. bank.

Carrie Freestone is an economist at RBC. She provides labour market analysis, and is a member of the regional analysis group, contributing to the provincial macro outlook.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.