British Prime Minister Boris Johnson recently proposed contentious legislation in preparation for the UK’s departure from the EU single market. The divorce will be final at the end of Dec. 2020, when the clock runs out on the one-year transition period during which the UK remains tied to the EU’s economic structures.

The Internal Market Bill would in effect negate much of the Withdrawal Agreement, the divorce settlement to which the UK and EU agreed late last year. The main point of contention is state aid: the British government has decided it now wants an unconstrained ability to subsidize companies and industries, something that would not be possible under the terms of the current agreement.

An important casualty of the demise of the Withdrawal Agreement would be the Northern Ireland protocol, which guarantees the Good Friday Agreement that prevents a hard border on the island of Ireland.

Should the prime minister’s proposal be passed in Parliament, and the UK renege on the Withdrawal Agreement, Britain would in effect breach international law.

The proposal was strongly condemned not only by the EU, but also by former Prime Ministers who want to protect the UK’s reputation as a staunch defender of the rule of law. Politicians in the U.S. soon joined in, with Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi and presidential candidate Joe Biden pointing out that the House of Representatives would be unlikely to approve a U.S.-UK free trade agreement (FTA) if the Good Friday Agreement were breached—a sign of the power of the Irish lobby in the U.S. An FTA with the U.S. was always much coveted by Brexit proponents, who saw severing ties with the EU as an acceptable cost to obtain it. With the EU accounting for close to 50 percent of Britain’s exports, a large alternative FTA is clearly needed.

Most observers expected negotiations to become increasingly acrimonious as the deadline to reach a trade deal with the EU approached. Few, however, could have predicted a move that could sully Britain’s international reputation.

Brexit brinkmanship: Does he mean it?

Is this simply a negotiating tactic, aimed at sowing havoc and preparing the ground for Britain to orchestrate a U-turn and agree to a trade deal? Or does Johnson believe the cost of leaving without a trade deal is a fair price to pay for the freedom to pick and choose industrial winners? Opinions are divided.

A deal, at least in the form of a rudimentary FTA covering goods, is still possible. After all, the EU would still prefer one, and many observers believe the UK authorities should not consider putting the country through an economic shock at a time when Britain is already weak due to the COVID-19 health crisis. The British economy has bounced back from its 22 percent year-over-year Q2 contraction, but the recent tightening of restrictions in response to a rising infection rate will likely hamper the recovery. For 2020, RBC Capital Markets expects UK GDP to contract by some nine percent year over year, a much deeper contraction than is expected in the U.S. (-3.5%) or Canada (-6%).

Brexit scenarios to year's end

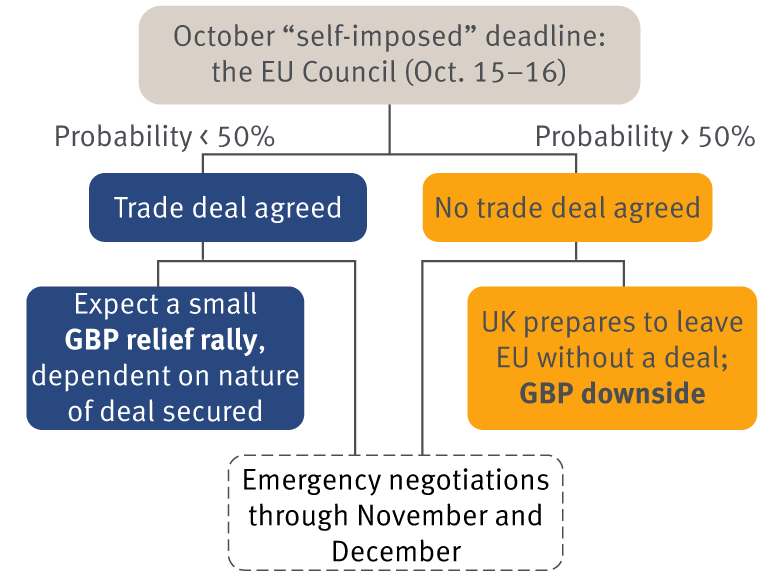

The scenarios start from the UK’s self-imposed deadline of October 15, 2020 when the European Council meeting begins. If the UK secures a trade deal with the UK before leaving the EU at the end of December, we expect a small relief rally in the pound, dependent on the nature of the deal. If no trade deal is agreed, we see downside risk to the pound. In either case, we expect emergency negotiations to take place in November and December.

Note: whether a trade deal is agreed or not, emergency negotiations are likely to take place as several issues will likely need to be ironed out.

Source - RBC Wealth Management

While a rudimentary FTA is still possible in theory, we continue to assign a probability of just over 50 percent to the UK leaving the EU without a significant economic arrangement on December 31. Time is quickly running out, and the prospect of a no-deal Brexit seems to inspire less fear in the EU than it did in the past, given the bloc’s recent creation of its ambitious fiscal stimulus package.

Staying Underweight amid poor visibility

The Bank of England is on high alert. With some of the government’s emergency support programmes becoming less generous, new COVID-19 restrictions taking effect, and the prospect of a no-trade-deal Brexit looming, the UK economy is likely to need more support in the months to come. To that end, the central bank has reiterated that negative interest rates are part of its toolkit, and is looking into how they could be implemented effectively. In the short term, we anticipate further quantitative easing focused on gilts (UK government bonds) before year’s end, with the potential for interest rates to be cut to zero later if deemed necessary.

For now, with a 6- to 12-month view, we would be Underweight UK sovereign debt. We expect gilt yields to grind higher over time as the effects of much higher government spending and accommodative monetary policy play out. Sterling investment- grade corporate credit provides relatively more compelling valuations, though we would be very selective given the double challenge of the pandemic and Brexit.

The prospect of negative rates, the recent resurgence of COVID-19 infections, and news of the government’s intention to negate the Withdrawal Agreement led the pound to retrace some of its recent gains against the U.S. dollar and the euro, falling five percent against the former so far in September. We believe trade negotiation headlines will be the most prominent driver of sterling in coming weeks. With risks asymmetric to the downside, we have a cautious outlook for the currency. The pound’s buoyancy so far this year suggests it is pricing in a 60 percent likelihood of a trade deal being signed, so it would likely retreat should this not materialise.

As for equities, valuations are undoubtedly attractive, with the FTSE All-Share Index close to where it stood following the 2016 Brexit referendum. But with the COVID-19 crisis far from being under control and a hard Brexit possible, we continue to believe there are better opportunities elsewhere and maintain our Underweight recommendation. We would focus on UK companies that are well positioned to benefit from long-term structural growth tailwinds or that have internal levers to grow, rather than on those whose prospects are tied to the macroeconomic environment.

Non-U.S. Analyst Disclosure: Frédérique Carrier, an employee of RBC Wealth Management USA’s foreign affiliate RBC Europe Limited, contributed to the preparation of this publication. This individual is not registered with or qualified as a research analyst with the U.S. Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (“FINRA”) and, since they are not associated persons of RBC Wealth Management, they may not be subject to FINRA Rule 2241 governing communications with subject companies, the making of public appearances, and the trading of securities in accounts held by research analysts.