Narratives and Markets

Pemberton Houston Willoughby was a niche, west coast investment firm that ran conservative money with swagger in the 1970s and 80s. In those days, the CEO of the company would know the front line investment advisors by name. It was like belonging to a family and corporate functions definitely had a family-like feel…even for a green rookie like me!

The firm would soon come to be known as Pemberton Securities and end up being swallowed up by Royal Bank and amalgamated into RBC Dominion Securities in 1989.

Just how different the culture was in the investment industry is too long of story for my short note. But believe me, it was totally different. For fun, I will share with you a couple of tidbits from that era. Remember, at this time there were only “brick” cell phones, no internet or lightning fast news transmissions.

A year before I started, an investment advisor would do their job tracking client accounts out of a series of binders. (As new rookies, we had to learn both the old-school binder method and the new computer based model).

You would have one binder with a printed record of the status of your client accounts. This record would show the same data as a client statement. It was updated on a weekly basis. Then you would transfer data from the client account sheets into other binders (by hand) where you could cross-reference what clients owned. Here are some examples of companies I remember owning for clients and cross-referencing: BCE, B.C. Telephone Company, International Nickle Company (Inco), Brascan, Falconbridge or Placer Dome.

These records were the mainstay of the pre-computer age advisor’s business. If something happened with one of the companies, the investment advisor could go to the binder and know all the clients who owned the impacted company and call them. There were a number of different cross-reference structures used, hence a few different binders.

The computer on the desk was basically just a quote machine to see the prices of the stocks intraday. To be fair, Pemberton had just introduced a platform that actually is still in existence today here at RBC called BERTON. (Taken from the PemBERTON name). It was ahead of its time and would force advisors away from the binder system. BERTON even had an internal email system included in its suite of services! It was funny to hear some of the old-timers saying how they didn’t trust the computer based system when it would actually make their life so much easier.

Another fond memory I have is of one of my colleagues Al Dreger coming into the office every Saturday morning to update paper charts on real graph paper. As a rookie I thought that was pretty cool! Computer charting was just getting going so these charts were invaluable.

Penny stock traders would show up in the front lobbies of the different investment firms and use the public quote machines that were fixtures of that era. That was the only way to get live quotes on stocks other than calling someone on the phone.

To put an order in for a client we had blue and pink tickets on our desk: Blue for buys and pink for sells. The advisor would write out the order on the appropriate ticket, take it to the wire operator in “the cage” and have them enter the order. A few moments later, the wire operator would get a wire back with the order confirmation details and the advisor would call the client with the fill details. Imagine how difficult day trading would be if we still had to do that?

Stocks traded in 1/8ths of a dollar on the exchange so the spreads were huge. Settlement date took 5 business days for a trade. A person could call in on the phone, with no existing account, and buy a stock in only a few minutes. There was even a thing called a “house account” where you could sell small positions of stock you may own in certificate form without even opening an account. The broker would just issue a cheque in your name a week later for the proceeds less the selling commission.

What really stuck me while reminiscing about this time in my career was the incredible lack of news flow. We literally read the newspaper with day old news in it to say informed. The Globe and Mail was the gold standard in Canada and, if you were a news junkie, you read both the Globe and the Financial Times!

If the stock market started to really move during the day, you had to turn on the radio to listen to the news to find out what had happened.

If you are old enough, try to remember how these same realities played into your life or career. It was just a more relaxed way to live.

Why am I taking this saunter down memory lane? Because I believe the shift to computer based asset management was instrumental in changing how financial markets functioned: And since that time there have been two more similar instrumental shifts.

The first came in June 2007 right before the Great Financial Crisis. It can be pinned to the 1st generation IPhones that I equate to the adaption of the handheld computer. It wasn’t until 2014 where the bandwidth and affordability caught up to the handheld technology but let’s stick with the 2007 date for now.

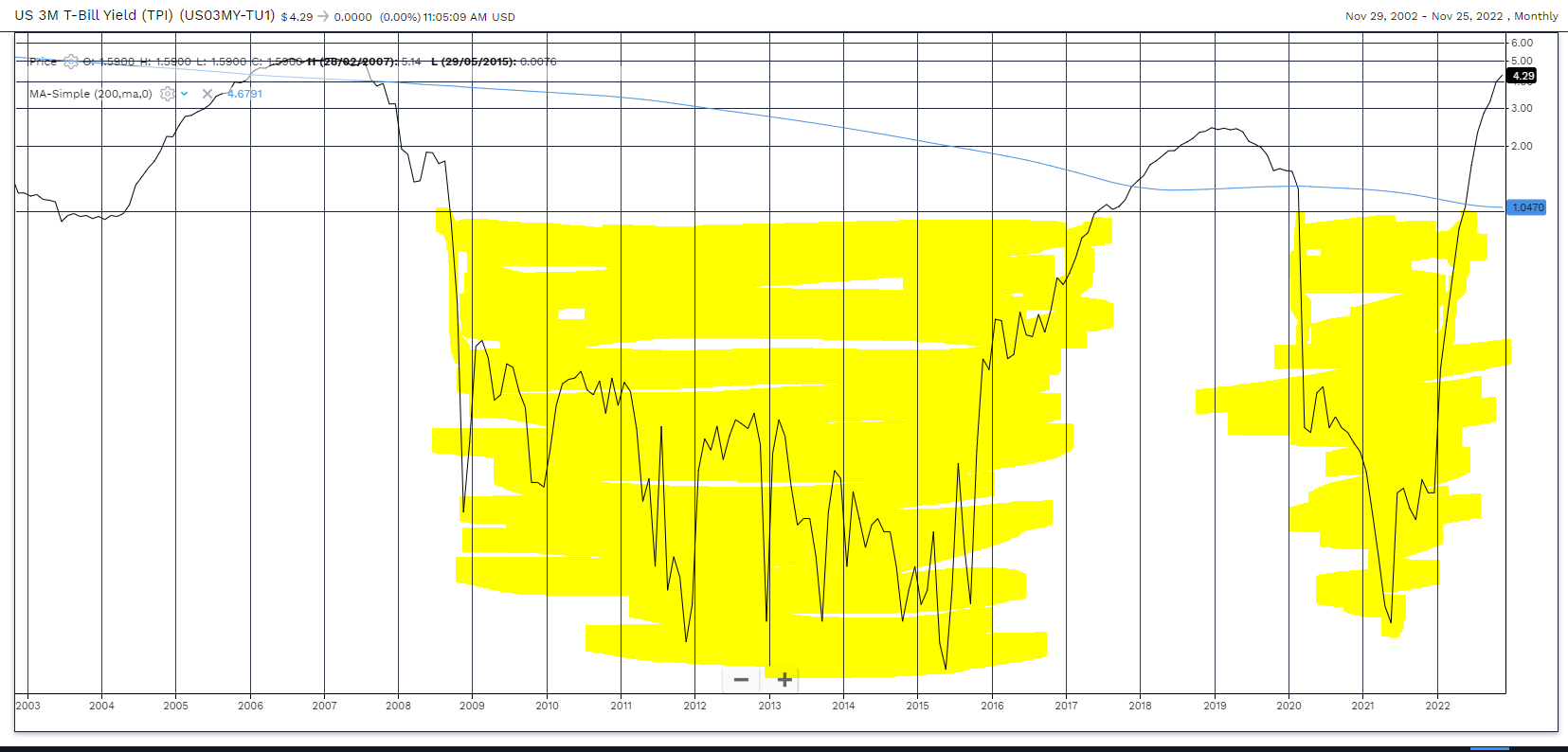

The second came in 2020 where financial market liquidity spilled over the central bank reservoir brims and flowed into the real economy igniting rates of inflation in 2022 that were not seen since the 1970s. The result is a world where interest rates are NOT going back down to the levels experienced for most of the past 13 years. (US 90 day T-bills below 1% for the last 20 years shown in yellow below).

So here is the rub: Back in the late 1980s and the 1990s there was a huge advantage to those who latched on to the technology change in the financial markets. The financial services business was now massively scalable relative to using a series of binders to keep track of things.

The shift to handheld computing was another easily identifiable alteration in the functioning of financial markets. The speed of transmission and range of access of information forever changed how markets would trade. Yesterday’s news was no longer a valid way to stay informed in terms of financial considerations.

The post 2020 financial markets are marking the end of “narrative driven market.” Don’t get me wrong, there will be great opportunities to buy investments that go up in price and make people wealthy who get in early. The change I am talking about comes at the core of the processing of the markets themselves.

With higher interest rates pinned against huge quantities of outstanding debt, the access to capital is more restricted. That is why Wall Street (and Bay Street) are begging for a central bank pivot to lower interest rates again. Without a pivot, the lack of liquidity facilitates and environment where Wall Street fails to make sufficient profits from PRICE movements of bonds and stocks and, therefore, has to rely more heavily on FLOW (market making) of capital.

In BEAR markets, when price stops providing lasting profits for investors, flow also dries up as investors and traders hunker down.

The final dagger in price action comes from the ability of savers to receive a reasonable return on their savings. As we have said in this letter before, a year or so ago, a person with $1,000,000 in savings only received $9000 of interest for the year on their 1 year deposit. Investing the same $1,000,000 today would see them receive $51,000 in interest for the year. That represents a significant competition to available capital now.

All of these facts are detrimental to “narrative-driven” investment ideas. Tech stocks, cryptocurrencies, penny stocks etc. cannot access cheap capital in terms of debt and equity as easily anymore. Without capital, these stocks tend to languish in price.

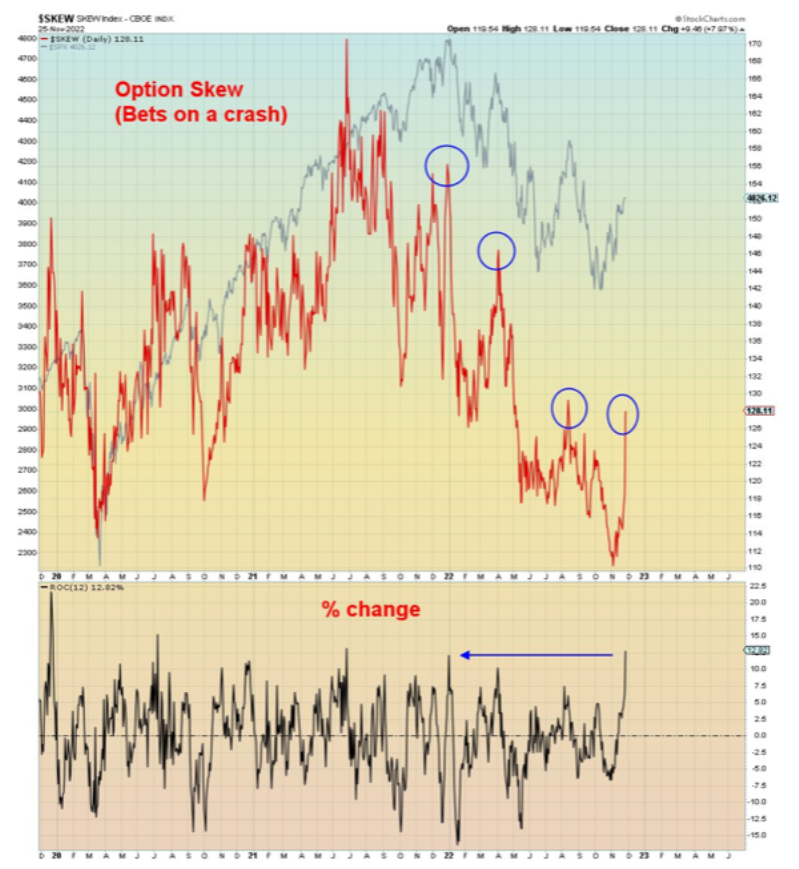

Sometimes we refer to financial markets that are constrained by these conditions as “choppy.” They tend to bounce up and down quickly based more upon mathematical constraints than “narrative.” (Below is a chart showing both outright and rate of change in option skew. Notice how skew has defined each of the rally peaks in the present BEAR market rally in stocks since the BEAR market began a year ago).

The average, long term investor can view this data from two perspectives.

- In the long term, holding quality stocks pays off with a solid, inflation adjusted return.

- In the short and medium terms, there are factors that will create periods of underperformance and drawdown in portfolios. These must be accepted as a long term investor.

That said, there is still a choice to be made. Is there any reason why an entire portfolio must be considered “long term, buy and hold?” Is there not a case for different investment strategies within the context of solid asset management?

Ultimately, it becomes a matter of choice.

As always, your questions or comments are welcome!