Currency Devaluation and Low Interest Rates

“When the four professional skydivers jumped out of the plane to perform their aeronautical stunts they were nervous that the strong winds would not allow them to do all of their usual tricks. Safety comes first, so they had to edit today’s show and make sure their parachutes were hair-trigger ready to deploy in case something went wrong.

At 14 seconds into the jump the divers made eye contact and began to situate themselves while free-falling for the opening trick.

All of a sudden, one of the divers accidentally caught her arm on the rip cord and her parachute deployed. The remaining divers almost immediately looked like specks as they accelerated away from her towards the earth.

There was nothing she could do but enjoy the trip down to the ground. Her role in the show was over for today.”

As the skydivers were in free-fall, they were all moving at the same relative speed. Yes it was more than 190 km/h, but because the speeds were equal, they could perform their show like they were standing on the ground. It was only clear how fast they were moving when one of the parachutes accidentally deployed and that divers’ speed slowed to a 30 km/h.

Sudden speed changes are happening in some financial markets too.

This weekly comment is going to feature two situations where “parachutes” have been deployed in the financial world. The first is an extreme example in a distant land…the second is closer to home.

The debate amongst economists about the impact of prolonged low interest rates on asset prices and everything else, is heating.

Some economists are using the low interest rate environment to JUSTIFY high asset prices, saying that continued low interest rates mean that stocks and bonds are not as expensive as many claim.

This is absolutely true. But the truth comes with a caveat. It is a mathematical truth, rather than a real life truth.

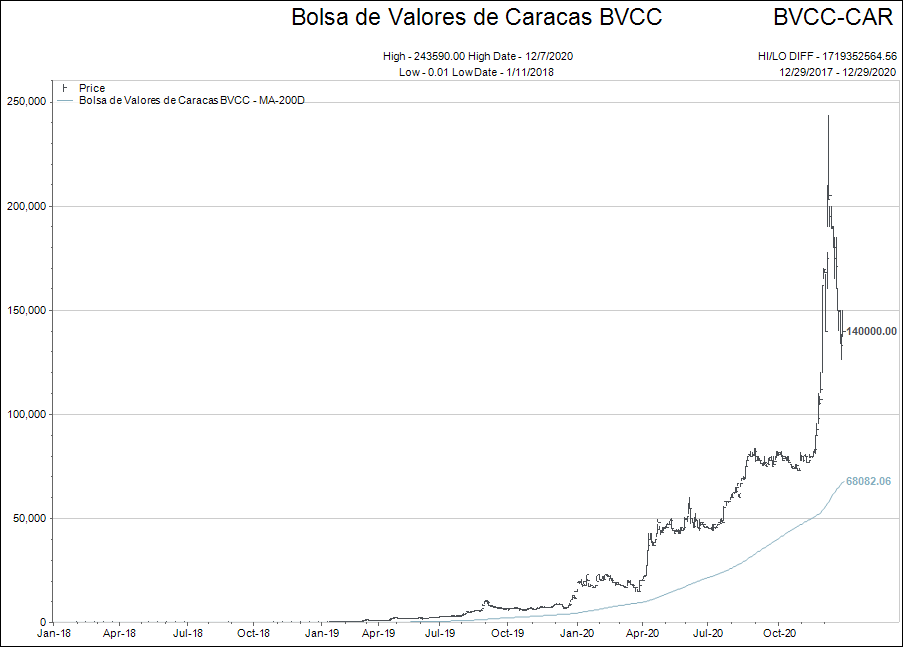

And maybe sky-high stocks don’t really signal a healthy economy anyway. Case and point: Let’s consider the Venezuelan stock market.

Before we look at the chart, let’s think about how life in Venezuela has been the past few years.

- Political instability,

- Growing poverty as income and wealth inequality surge,

- High COVID numbers,

- Tremendous food shortages,

- Resource bottlenecks, and

- Hyperinflation.

To grasp the kind of hyperinflation Venezuelan’s are experiencing, take the cost of a simple cup of coffee. Denominated in local currency, back in 2018, a cup of Joe would have run you 400 Bolivars, but presently, in December 2020, this same cup will ring in at more than 1,000,000 Bolivars.

Given those conditions, how do you think their stock market has performed?

Did you expect to see chart of the stock market that went parabolic in its home currency?

Congratulations to those of you who did because that is exactly what one expects in a hyperinflation.

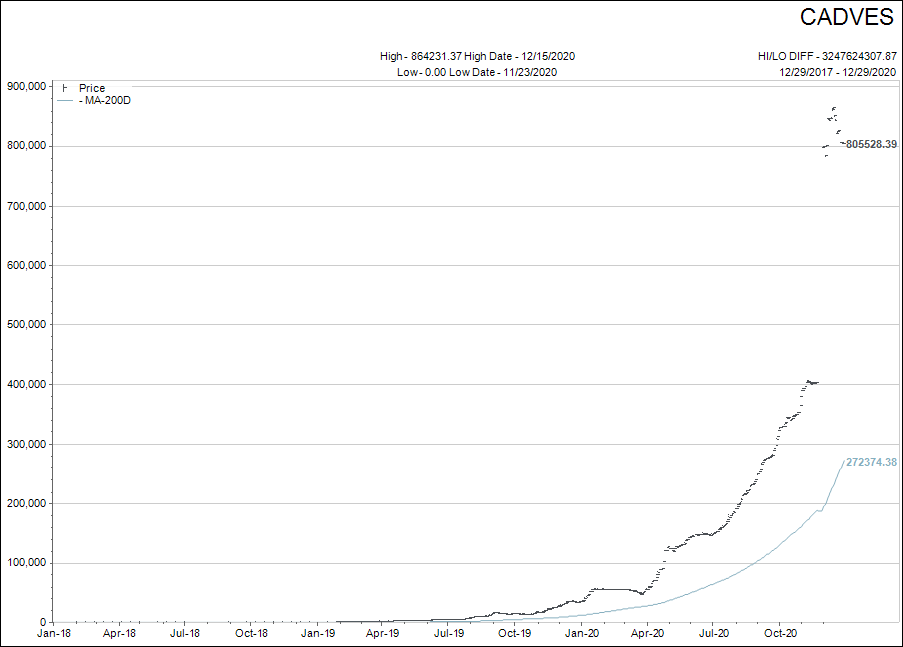

Now let’s view the Venezuelan currency relative to the Canadian dollar.

Again, no surprise here. The currency has been destroyed.

What would it have been like if a Canadian investor had invested in the Venezuelan stock market in 2019?

One Bolivar would now be worth 190,000 Bolivars via the stock market return, but each dollar the Canadian exchanged into Bolivars would have to be converted back to Canadian today at 1/800,000th of its original value.

What that means is a Canadian investor would only have one quarter of their original investment…even though the stock market went up astronomically.

This was once a rich country that has been ravaged by very poor leadership and hyperinflation. Imagine what people’s pensions, wages and savings look like in Venezuela when trying to purchase imported goods. (Click here for a short Washington Post story about Christmas 2020 in Venezuela).

So here’s a question: Could some milder form of inflation be ravaging the savings of North Americans?

The answer, of course, is yes, but it is important to understand that once “we choose” a fractional reserve banking system, inflation must remain present within the system or it breaks down.

The real question is: Are Canada and the US moving past “garden variety inflation” to something more serious again…akin to the 1970s?

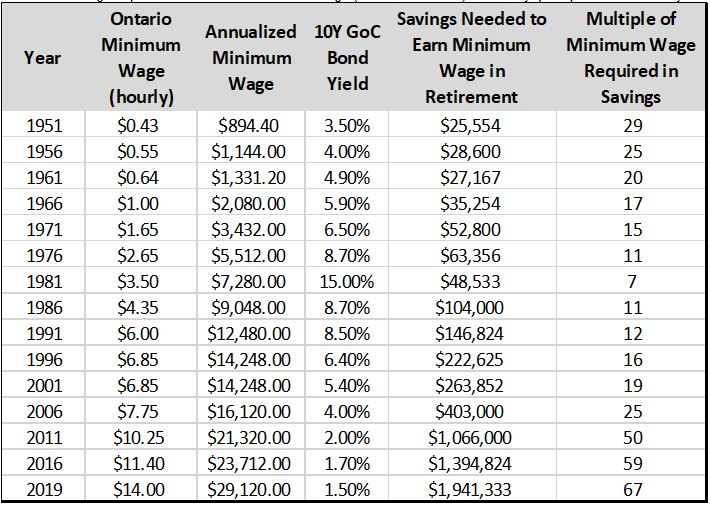

The graphic below is from one of my 2019 editorials. When I first posted the graphic it struck me as being as extreme as it could ever be…and then, well, 2020.

What we are comparing is historical minimum wage in Ontario relative to the savings one required in that year to generate the same income as minimum wage provided holding a 10 year Government of Canada bond.

(At the bottom of the chart I have manually added in 2020)

2020 $14.25 $29,640 0.75% $3,953,000 133

To be clear, in 2020 it would require $3,953,000 (133 times minimum wage) to earn the $29,640 at a 0.75% interest rate.

Take a few moments and look at the chart.

Think about what life was like at some of those times.

For younger readers, this will be tough, but for older readers it will likely bring you to some interesting conclusions.

In classical economic thought, one would guess if they could see nothing but the data on this chart, that Canada would be caught in a massive deflationary bust where asset prices were falling. That is the only way that an organically functioning economy could every drive interest rates to such low levels.

Obviously, this is not the case.

One last point to wrap up this primer to the Year End Review to come in early January.

Hyperinflation always involves massive devaluation in the underlying currency unity. As it can be seen in the Venezuelan example, the currency “gapped” lower when the artificial supports could no longer be held in place. The crash in the currency can easily be seen on a chart.

What you can’t see and feel on a chart is what was happening to the psychology of the people in the hyper-inflating country (Venezuela) in the months leading into the currency crash.

In a nutshell, consumers spent at a faster rate than normal, for fear of loss of purchasing power on their savings. Cash was trash and everyone tried to deploy their cash at the same time, creating a scarcity of goods and services.

The escalation of the fear of loss of purchasing power is always step one in above average inflationary periods. Inflationary psychology is difficult to reverse once it takes hold.

Is 2021 setting up for a jump in inflationary psychology for Canada and the US?

This is where I will meet you in a weeks’ time to discuss a few details about the 2020 financial year and a couple of thoughts to what 2021 might look like.

Where the world goes from here is anyone’s guess? All I know for sure is we have never been here before.

Friends these are the crazy outliers that exist in a world where central banks choose to mess around with money supply and interest rates.

Back to our analogy of the skydivers. You just never know when the parachute might deploy changing everything in a short period of time.

Feel free to send me your thoughts about this weekly.