How People Feel About Their Relationship with Money

Money, wealth and net worth are terms that mean different things to different people.

Your definition depends upon how you were raised, how you were educated, and frankly, how much wealth you have.

A colleague of mine shared an article with me from Scientific American entitled Is Inequality Inevitable? that makes an excellent observation under pure capitalistic conditions…but when was the last time the financial world represented pure capitalism?

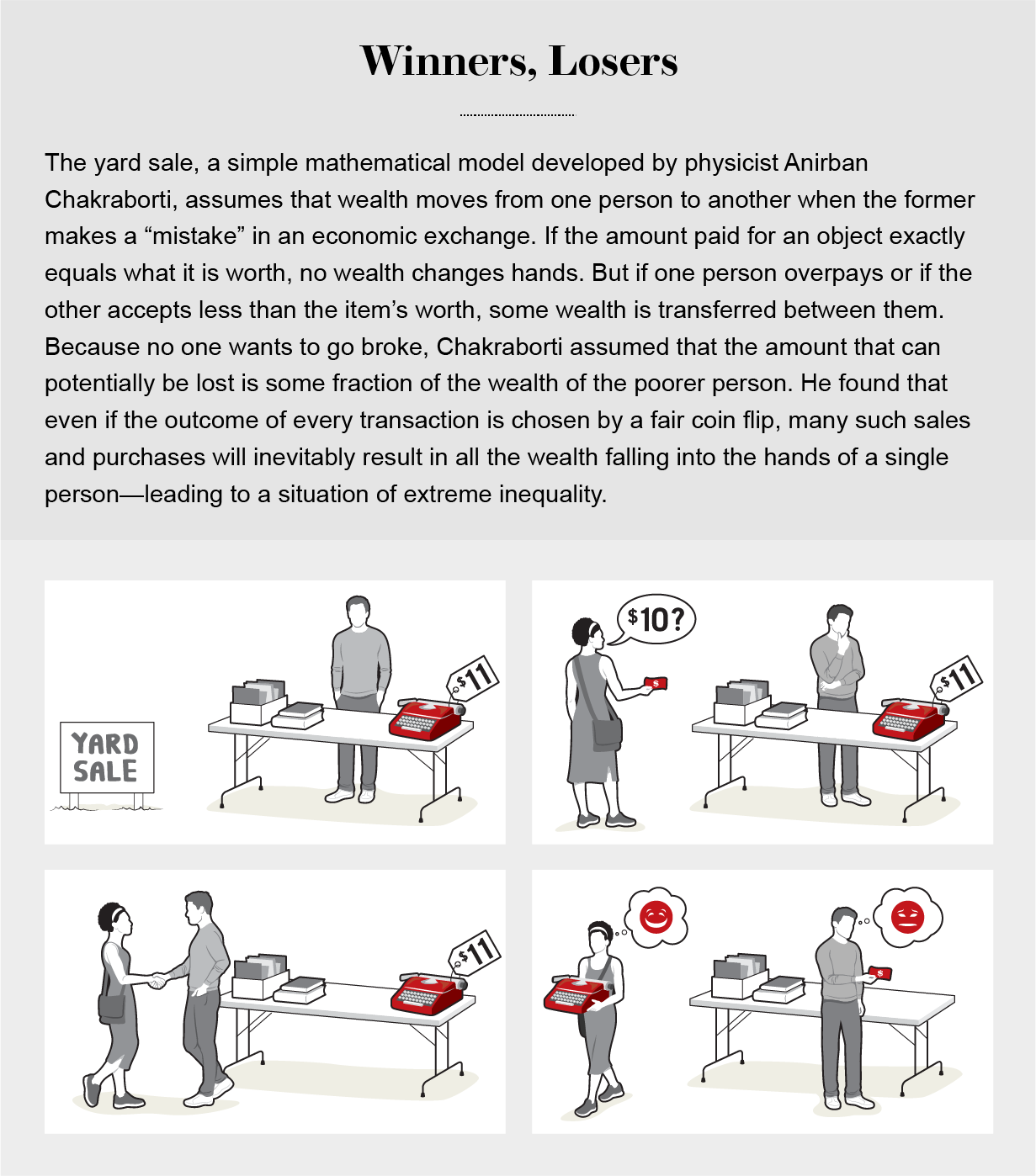

The graphic below summarizes the theme presented in the article as to how wealth inequality is a natural byproduct of capitalism.

I fully agree with the process outlined in the “yard sale model,” but it doesn’t really describe what has taken place in the financial world; especially since Alan Greenspan’s Fed decided to manage asset prices starting with the 1987 stock market crash.

The yard sale model assumes two willing participants agreeing on a transaction price. The exchange process assumes that both the buyer and the seller have searched the market and concluded their deal represents the best price for their interests in a process is called “price discovery."

Now let me change the yard sale example slightly.

The typewriter seller in the graphic wanted $11.00 for the item, the purchaser offered $10.00. Again, we assume both participants understood the typewriter market and believed they were getting the best deal possible. Therefore, they agreed on a price and a transaction took place.

But the typewriter buyer knew that a third agent with unlimited amounts of money was present. This third agent was going to keep buying all the typewriters they could get their hands on, not because they needed typewriters, but because they needed transactions to make the economy appear to be strong.

The seller either did not have the same information or might have just needed the money to pay for rent, or buy groceries.

In this example, the typewriter buyer is going to get much wealthier in a much shorter period of time than in the basic yard sale example because the price of typewriters will ramp higher with an indiscriminant buyer in the market place.

In essence, this is exactly what central banks around the world have done by engaging in Quantitative Easing (QE).

Rather than going into any further into the monetary policy part of this story, let’s shift gears and look at two segments of our society that have come out on the losing side of the QE saga.

The Millennial Generation theoretically should be “hitting their economic stride” right now, demographically speaking, and we know that this is far from true.

How far?

In 1989, when the average Baby Boomer turned 35, their generation had accumulated 21% of total wealth in America.

In 2008, when the average Gen Xer turned 35, their generation had accumulated 8% of total wealth in America.

In 2023, the average Millennial will turn 35. So far that generation has accumulated 3% of total wealth in America.

Obviously, many factors go into those statistics, but global monetary policy is a huge driver of the problem.

So here is the question:

How does someone with few or no assets compete when there is a buyer with unlimited assets and no price discretion in the market buying everything in sight?

Understand though, that it is not the central banks directly buying all the assets. They are just the monetary arsonists pouring the gas on the rapidly-escalating-asset-price-fire by creating the cheap money and monetary conditions.

It is a difficult problem, which has taken 40 years to metastasize, and has no short term cures.

The second group I want to focus on is the “senior saver.”

These are people above the age of 60-years-old who have generally kept their modest savings in safe, interest bearing investments. As a group, senior savers had a caretaker-like relationship with the future. They sacrificed from their present consumption over their lifetimes to acquire a modest nest-egg, and they have expected that nest-egg to give back to them in their later years.

Unfortunately, their safe assets did not appreciate in proportion to the increase in their costs of living, and their relative lifestyles suffered.

It is a weird to think about. The moral hazard introduced by central banks over the past 40 years has impacted these conscientious senior savers and brought them to a place of questioning their care-taker roles in society. The result has been a strong sense of betrayal.

Ironically, senior savers acted astutely over their lives and they believed in a future where prudence would be rewarded.

They took responsibility for themselves and their families…yet, the orchestrators of the system did not hold up their end of the bargain.

As a group today, senior savers feel like they were duped, or at the butt end of an awful practical joke. In reality they were just part of what has happened many times in history which is the devaluation of currency to keep the elites wealthy.

In summary, it is difficult to for people to change their monetary personalities: Savers tend to stay savers, spenders like to spend.

Maybe the future will see some justice done for the senior savers of the world. A serious deflationary period would help their cause. Who knows?

The millennials will have a more likely positive outcome.

In coming years millennials will take over the seats of power and decision making. They will tip the scales in their favour like every other generation has done when it gets to call the shots.

We do live in interesting times.

As always, don't hesitate to reach out with any questions, comments or concerns you may have, and Megan and I hope you have a wonderful week.