For business owners who may be looking to exit their business in the not-too-distant future, determining the value of the business is a crucial step.

According to a 2023 KPMG survey, a significant demographic shift is underway in Canada among business owners. The survey found 73 percent of family business leaders are expecting to transition to new leadership in three-to-five years.

Even for business owners who aren’t planning their retirement and intending to sell their business to provide a source of funds, having a clear idea of their company’s value can be important in other situations as well (for example, if considering an estate freeze).

When it comes to accurately assessing business value, it may be wise to consider hiring a valuation specialist. When valuing a business, these specialists generally calculate the fair market value. The specific approach and factors to consider will vary in each case, but in the valuation of privately owned businesses, there are three generally accepted methods: an asset-based valuation, an income-based approach and a market-based approach.

Note: The following information provides an overview of business valuation approaches. Given that every business situation and structure is unique, it is crucial to consult with your qualified advisors and tax and legal professionals to ensure your circumstances and needs are appropriately addressed and that the most suitable process is undertaken to accurately determine the fair value of your business.

1. The asset-based approach

This approach involves calculating the value of a business based solely on the value of its net assets. It’s generally used in the following situations:

- When the value of a business is closely related to the value of its underlying assets, as in the case of an investment company or a real estate holding company

- When the assets of a business are not generating adequate returns the way they are currently being used, as in the case of a business generating nominal earnings, and their value could be maximized by some other use or by their sale

- Where the value of the business is attributable to the current owner’s personal attributes or relationships and is not transferable to a new owner. For example, if the relationship between the customers and the company are unlikely to continue should the current owner not be involved in the business

Using this approach and assuming the business is viable, the fair market value of all the assets and liabilities of the business is determined. Generally, a valuator would consider the following:

- Whether a write-down of any accounts receivable is required to reflect any potential bad debts

- Whether on-hand inventory could be sold for an amount higher or lower than its book value

- Whether an appraisal from a specialist is required to determine the fair market value of certain assets (e.g. real estate or machinery)

- The potential disposition costs associated with the assets and liabilities. For example, consider not only the fair market value of a real estate property, but also any costs associated with its sale, such as legal fees, commissions and taxes. A potential purchaser would likely require a discount on the purchase price to reflect these costs

With this approach, the net amount of fair market values of the assets and liabilities represents the fair market value of the common shares of the business.

2. The income-based approach

This method is appropriate where the business is generating an adequate return on its capital and a theoretical purchaser is interested in acquiring the business’ future earnings or cash flows. This approach is suitable where the earning power of a business is greater than the value of the individual assets owned by it. The capitalized earnings approach, capitalized cash flow approach and discounted cash flow approach are various income-based tactics that can be used to value a business.

Let’s focus on the capitalized earnings approach, as this is applicable to a mature, established business. This kind of business would not need to invest in major capital assets and its future earnings are generally predictable and can be reasonably estimated.

To determine the value of a business using this approach, the expected annual future earnings of the business, or its maintainable earnings, should be calculated. The business’ historical financial results can provide an indication of this. However, you may need to adjust the historical earnings to eliminate the impact of any nonrecurring or uneconomical items, such as:

- Compensation, including salaries and any personal benefits, paid to non-arm’s length individuals who are either above or below the economic compensation levels for the position

- Gains or losses earned in a year that are unlikely to recur in the future, such as a gain or loss from a one-time sale of an asset

The maintainable earnings are then multiplied by an earnings multiple. This multiple is the inverse of the rate of return required by a theoretical purchaser on their investment in the business. For example, a purchaser requiring a return of 20 percent on their investment would multiply the maintainable earnings figure by five (1/20% = 5) to calculate the value of the business. Note that the rate of return a theoretical purchaser will require changes over time and according to the situation and will reflect the risk of the particular investment being analyzed. A theoretical purchaser would likely consider risks such as:

- Nature and history of the business

- Customer base

- Management team and employee experience and qualifications

- Financial position

- Ease or difficulty of entering the industry

- Industry trends and challenges

- Economic and financial conditions

- Competition

- Current rates of return on alternative investments, including the risk-free rate

There are several methods that can be used to determine the appropriate rate of return to value a business. The weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is a method that’s commonly used. The WACC is the rate of return determined by the weighted average cost of debt and return on equity. A valuation specialist usually assists with this calculation. When the WACC has been determined, the inverse of the WACC is the multiple used to value the business.

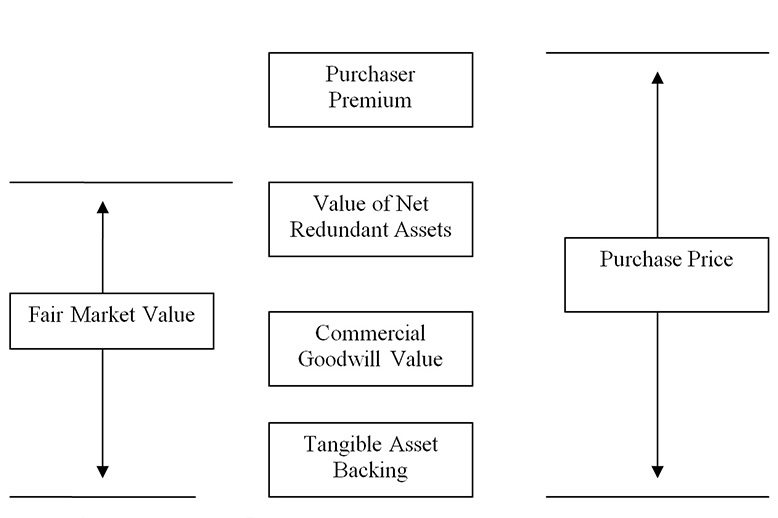

The maintainable earnings are multiplied by the multiple to calculate the enterprise value. The enterprise value represents the fair market value of the net assets used in ongoing operations (known as the tangible asset backing) and the value of the goodwill that can be transferred to a potential purchaser (known as the commercial goodwill). The fair market value of any assets owned by the business that are not employed and required in its day-to-day operations, known as redundant assets, is then added to this value.

The total of the enterprise value and the fair market value of the redundant assets represents the value of the business as a whole. The value of all outstanding interest-bearing debt is subtracted from this amount to determine the fair market value of the common shares of the business.1

3. The market-based approach

The market-based approach is the most common method in a sale of a business. It uses data regarding the market valuation of public and other private companies that are reasonably comparable to the business being valued. Comparable companies are those which operate in a similar industry and region as the business being valued and, when possible, should be relatively the same size (similar revenues or number of employees, etc.). The two significantly used market-based approaches are the precedent transaction multiple approach and the public company multiple approach.

In the precedent transaction multiple approach, implied valuation multiples are derived from acquisitions of private companies that operate in the same industry as the business being valued. For example, let’s assume an owner is interested in valuing their business and has identified two comparable private companies recently purchased in two separate, independent transactions:

- 100 percent of the common shares of Company A (which has no debt), with an EBITDA2 of $2 million, and using a multiplier of five, was acquired for $10 million

- 100 percent of the common shares of Company B (which has no debt), with an EBITDA of $4 million, and using a multiplier of four, was acquired for $16 million

Using this data, the owner could determine the enterprise value of their business by multiplying their business’ most recent maintainable EBITDA by 4.5, the average implied EBITDA multiple in the two private transactions. The owner would then add the fair market value of any redundant assets and subtract the value of all interest-bearing debt to determine the fair market value of the common shares of their business.

In the public company multiple approach, a business is valued based on the valuation multiples derived from the enterprise value of publicly traded comparable companies. For example, let’s assume an owner is interested in valuing their business and has identified two comparable public companies, with no debt, that have the following most recent trading information:

- Company A, with annual sales of $150 million, has an enterprise value of $132 million

- Company B, with annual sales of $160 million, has an enterprise value of $128 million

The average enterprise value-to-sales multiple implied in the two public companies is 0.84. As public companies are generally much larger, operate in more regions and are more diverse than private companies, it’s inappropriate to value a private company using the same public company multiple, without considering a discount.

In this situation, let’s assume a valuator determined that a 45 percent discount is appropriate. The owner could then determine the enterprise value of their business by multiplying their business’ most recent maintainable sales by 0.46, the average implied sales multiple in the two public companies, less a 45 percent discount. The owner would then add the fair market value of any redundant assets and subtract the value of all interest-bearing debt to determine the fair market value of the common shares of the business.

Fair market value versus price

When an individual has determined the value of their business, does that mean they know the amount they can sell their business for? Not necessarily. In an actual sale, potential purchasers may be willing to acquire a business for a price that’s different from the business’ fair market value.

This could be based on several factors, including the negotiation abilities and financial strength of both parties and the purchaser’s ability to utilize the business’ assets in a manner particular to them. For example, a purchaser may be willing to acquire a business at a price higher than its fair market value because of potential synergies that could be realized following the acquisition. These synergies may not be available to other purchasers, and as such, they would not be willing to pay the same price.

Determining the fair market value of a business, however, provides business owners with a gauge to measure the fairness of any potential purchase offer and a measurement of the current financial condition of their business.

References:

- This is only done if interest expense has not been considered in determining maintainable earnings.

- EBITDA is a financial metric reflecting a company’s earnings before interest payments, depreciation, amortization and taxes.

This document has been prepared for use by the RBC Wealth Management member companies, RBC Dominion Securities Inc. (RBC DS)*, RBC Phillips, Hager & North Investment Counsel Inc. (RBC PH&N IC), RBC Global Asset Management Inc. (RBC GAM), Royal Trust Corporation of Canada and The Royal Trust Company (collectively, the “Companies”) and their affiliates, RBC Direct Investing Inc. (RBC DI) *, RBC Wealth Management Financial Services Inc. (RBC WMFS) and Royal Mutual Funds Inc. (RMFI). *Member-Canadian Investor Protection Fund. Each of the Companies, their affiliates and the Royal Bank of Canada are separate corporate entities which are affiliated. “RBC advisor” refers to Private Bankers who are employees of Royal Bank of Canada and mutual fund representatives of RMFI, Investment Counsellors who are employees of RBC PH&N IC, Senior Trust Advisors and Trust Officers who are employees of The Royal Trust Company or Royal Trust Corporation of Canada, or Investment Advisors who are employees of RBC DS. In Quebec, financial planning services are provided by RMFI or RBC WMFS and each is licensed as a financial services firm in that province. In the rest of Canada, financial planning services are available through RMFI or RBC DS. Estate and trust services are provided by Royal Trust Corporation of Canada and The Royal Trust Company. If specific products or services are not offered by one of the Companies or RMFI, clients may request a referral to another RBC partner. Insurance products are offered through RBC Wealth Management Financial Services Inc., a subsidiary of RBC Dominion Securities Inc. When providing life insurance products in all provinces except Quebec, Investment Advisors are acting as Insurance Representatives of RBC Wealth Management Financial Services Inc. In Quebec, Investment Advisors are acting as Financial Security Advisors of RBC Wealth Management Financial Services Inc. RBC Wealth Management Financial Services Inc. is licensed as a financial services firm in the province of Quebec. The strategies, advice and technical content in this publication are provided for the general guidance and benefit of our clients, based on information believed to be accurate and complete, but we cannot guarantee its accuracy or completeness. This publication is not intended as nor does it constitute tax or legal advice. Readers should consult a qualified legal, tax or other professional advisor when planning to implement a strategy. This will ensure that their individual circumstances have been considered properly and that action is taken on the latest available information. Interest rates, market conditions, tax rules, and other investment factors are subject to change. This information is not investment advice and should only be used in conjunction with a discussion with your RBC advisor. None of the Companies, RMFI, RBC WMFS, RBC DI, Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates or any other person accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or the information contained herein.

®/TM Registered trademarks of Royal Bank of Canada. Used under licence. © 2024 Royal Bank of Canada. All rights reserved.