While inflation has stayed calm in 2025, concerns about potential tariff-related price hikes have kept the Fed sidelined.

Today we’ll analyze recent commentary, the impact of market forces and political pressure on yields, and the probability of future rate cuts.

As was widely expected, the U.S. Federal Reserve held rates steady for the fourth consecutive meeting.

It was at the first of those meetings back in January where Fed Chair Jerome Powell, when asked about the potential impact of tariffs on inflation under the incoming administration. Powell stated that there are many places that price increase from tariffs can show up between the manufacturer and a consumer.

“So, we’re just going to have to wait and see”, he concluded.

So, after months of waiting, inflation data continues to underwhelm.

Consumer Price Index (CPI) data through May showed headline inflation had been running at an annualized rate of only 1.0% over the prior three months. Core inflation (excluding volatile food & energy components) was also running at just 1.7% - both shy of the Fed’s 2.0% target.

The Fed however, is only concerned about what the future might hold.

Updated inflation forecasts showed Personal Consumption Expenditures (Fed’s preferred measure of inflation) rising to 3.0% by the end of the year, up from a forecast of 2.7% in March.

It’s not only the Fed that expects the tariff-related impact on inflation to materialize later this year - most economists, consumer surveys, and numerous surveys of businesses indicate the same

As the chart below shows, a survey from the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) of service-sector businesses showed that 45% of those surveyed believe prices are higher relative to the month before. This is the highest response since January 2023.

RBC Economics expects that to rise to 2.9% in the back half of the year. Other market-based measures from the CPI swaps market suggest the annual rate of inflation could rise higher still to north of 3.0% by year end.

While it may be fair to ask why  the Fed isn’t cutting rates at the current juncture, the Fed’s updated rate projections showed that the median member still expects two rate cuts this year.

the Fed isn’t cutting rates at the current juncture, the Fed’s updated rate projections showed that the median member still expects two rate cuts this year.

Of the 19 policymakers on the Federal Open Market Committee, eight projected two 25-basis-point rate cuts by December. At the other end, there’s a growing cohort that sees no rate cuts this year.

U.S. President Trump again this week had sharp criticism of Powell, expressing his desire to see 200 basis points of rate cuts immediately. He stated that the Fed’s inaction is costing the U.S. “hundreds of billions” of dollars in financing costs.

To be sure, the Fed is certainly a powerful institution, but it doesn’t act in isolation and, like so many other things, is not impervious to economic or market forces.

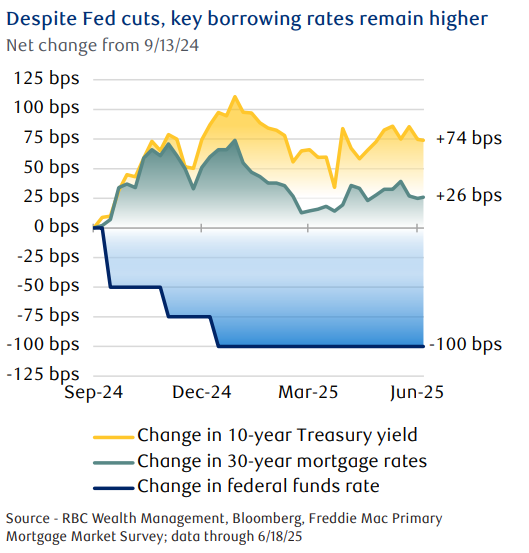

The second chart shows that market forces have also defied the Fed’s actions thus far.

Despite already cutting its overnight policy rate by 100 basis points to 4.5% from 5.5% late last year.

The key 10-year borrowing rate for the U.S. has risen by nearly 75 basis points to around 4.4%.

The average 30-year fixed mortgage rate has increased by 26 basis points to 6.8%.

The market is saying that tariffs raise risks of inflation and that potentially higher deficits, should unfunded tax cuts come to pass.

The market is saying that tariffs raise risks of inflation and that potentially higher deficits, should unfunded tax cuts come to pass.

This would likely add to those pressures, while also adding to the debt burden, and simultaneously boost the growth outlook.

All of these things actually limit the Fed’s ability to cut rates.

If the Fed were to cut its short-term policy rates now—at a time of economic strength, market forces would only propel more of what we have already seen: higher Treasury yields and, consequently, higher government, consumer, and business borrowing rates.

This would all serve as a good reminder to investors that high interest rates should generally be seen as a positive thing. They are a sign of economic strength and stability.

Nonetheless, some in the U.S. would likely love nothing more than a return to the era of free money and low interest rates that prevailed during a time of sluggish growth.

If the administration’s policies are largely at odds with lower interest rates, the Fed, while powerful, may be powerless to do anything about it.

As always, please let me know if you have any questions or comments.