Long-term economic trends have left the U.S. economy increasingly reliant on spending by upper-income households.

Let’s unpack the potential implications for economic stability and Federal Reserve policymaking.

In recent years, The U.S. has cut interest rates to zero, extended forgivable loans to business owners, and distributed direct support to households.

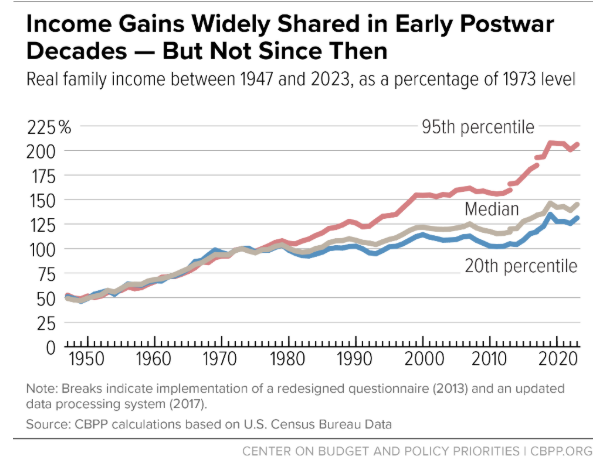

While some of the programs were spurred by the global financial crisis, many were effectively unprecedented in modern times. The firepower was largely successful in combatting an economic slowdown, the post-pandemic period has seen a sharp improvement in outcomes for higher-income households, along with stagnation and relative decline for those with lower incomes.

This has left the U.S. with what is effectively a two-tier economy.

Upper-income households are increasingly driving the economy and reaping the benefits of its advance, while lower-income and newly formed households face a narrowing path ahead. This leaves the U.S. economy less resilient, more prone to shocks, and with a potential structural need for a weaker dollar.

The largest component of the U.S. economy—by far— is household consumption, which routinely accounts for almost three times as much economic activity as government spending or business investment.

Consumption comes from the top 10 % of households by income. In the second quarter of 2025, these consumers accounted for almost 50% all household spending, up from just over 30% in the early 1990s. Put differently, consumption by 10 % of households was behind 34 % of all economic activity in the United States.

It’s no coincidence that the top 20 % of households by income directly or indirectly hold 90 % of stock investments and that the ramp-up in consumption is concurrent with all-time highs in U.S. equity indexes.

It’s no coincidence that the top 20 % of households by income directly or indirectly hold 90 % of stock investments and that the ramp-up in consumption is concurrent with all-time highs in U.S. equity indexes.

The obvious implication is that demand for nearly a third of the goods produced in the U.S. relies on a very small slice of its population whose consumption behavior is almost certainly driven at least in part by the performance of the stock market.

The circular nature of that relationship—with stock prices fueling demand that drives corporate earnings that lead to higher stock prices— means that even a relatively small shift in consumption patterns could have large implications for the overall economy and global equity performance.

How did we get here ?

- U.S. Federal Budget: Larger tax deductions and expansionary fiscal policy have had both direct and indirect economic benefits for wealthy households with large investment portfolios.

- Declining Wage Impact: Viewed from the income side of GDP, labor’s share of national production has been falling since 2001. For folks without investment income, the result is a relative decline in economic participation.

- Changes In Monetary Policy: The global financial crisis forced countries around the world to keep interest rates artificially low. This policy was intended to help support asset prices, propping up banks and investors facing large write-downs on defaulted loans, and it was largely successful. The side effect, however, was that rising asset prices made it more expensive for income-constrained workers to purchase homes or build savings portfolios.

- Technology: Income disparity arose alongside revolutionary changes like the rise of the internet and the launch of practical artificial intelligence (AI). The flow of rewards for those world-changing innovations to their creators has tended to exacerbate inequality.

What cannot be reasonably disputed is that the U.S. today is near the highest levels of economic inequality in nearly 60 years.

The cleanest way to break up the current stagnation in economic mobility would be to move wage-dependent households into the investor class.

For instance, although average wages are up a hefty 77 % since 2007, rent has risen 90 % over the same period. That 13 % relative rent inflation is a major drag on the U.S. economy given that the overall savings rate is only 4.6 % of disposable income. Add in food inflation and a general rise in the cost of living—not to mention the impact of high student debt levels—and the mathematical reality is that there are severe practical limits on how much younger households can save.

Home ownership has been the path to wealth accumulation for U.S. households. Absent a policy shift, however, it’s difficult to see how low savings and high home prices will allow the next generation of North Americans to enjoy the same access to home ownership as the Baby Boomers.

A narrow base for economic growth has potentially large implications for the Federal Reserve.

Traditionally, the U.S. central bank has cut interest rates to spur investment and hiring, based on the idea that consumption by the newly employed would lead to a virtuous cycle of economic expansion.

Today, the case for that type of accommodation looks weaker.

The Fed acts on through two related channels.

- Lowering Long-Term Rates: which makes future cash flows more valuable today.

- Currency Debasement: rate cuts that weaken the dollar.

Both a lower discount rate and a weaker currency tend to drive up equity and real estate prices.

This type of policy framework has 3 important implications:

- Reliance On Longer-Term Interest Rates. The Fed cannot directly control long rates by adjusting its overnight policy, forcing it to consider less conventional tools like bond purchases.

- It Take 2 To Tango: Other countries may not play along with moves that benefit the U.S. to the detriment of overseas producers. Currency wars are potentially problematic across dimensions of international trade.

- There Is A Limit To What The Fed Can Do: Negative interest rates notwithstanding, Fed is stopped at 0.00%. Once it is reached, the U.S. will either have to generate true growth or face the potential economic consequences.

The key takeaway is that the longer the central bank is in the business of asset price support, the more painful it is to get off the treadmill.

In summary:

- Debt growing at an unsustainable pace

- A 2-tier economy

- Economic growth increasingly dependent on a base of upper-income spending and a weaker dollar

These challenges can be overcome, but doing so will require a degree of political unity and a rational discourse on burden sharing. While such a scenario may seem remote, facts and economic reality will force that conversation.

However…… the longer one waits, the more expensive the adjustment is likely to be

If you have any questions or comments, please do not hesitate to let me know