The terms ‘corporation’ and ‘company’ are used interchangeably in this article. A Canadian-controlled private corporation (CCPC), in simple terms, is a Canadian corporation that isn’t controlled by a non-resident of Canada or a public corporation or a combination of both. In addition, no class of shares of a CCPC can be listed on a prescribed stock exchange.

Please note that this article primarily refers to federal tax rules and rates. Certain provinces, such as Ontario and New Brunswick, don’t limit access to the SBD due to passive investment income earned in a corporation for provincial tax purposes. You should consult with a qualified tax advisor to determine the rules relating to your specific province/territory of residence.

You may accumulate profits in the company and invest in securities or other assets to generate investment income when the funds aren’t required for personal use or reinvestment in your business. You should note, however, that earning passive investment income in a private corporation may impact your corporation’s ability to access the small business deduction (SBD). The SBD results in a lower rate of tax on active business income earned by a corporation and creates an opportunity for tax deferral. The rules that restrict access to the SBD where a corporation earns passive investment income are discussed in more detail below.

Limiting access to the SBD

There may be a tax deferral advantage for business owners who retain after-tax income in their corporation. This is because business income earned in a corporation is generally taxed at lower rates than business income earned personally. If an individual is in the highest marginal tax bracket and earns business income, this income is subject to tax at a federal tax rate of 33%.

A Canadian corporation, on the other hand, is subject to a general federal corporate tax rate of 15% on its active business income (ABI). In addition, if a corporation is a CCPC throughout a tax year, it may benefit from the SBD which can lower the federal tax rate to 9% on the first $500,000 of ABI (known as the “business limit”).

The business limit must be allocated among all corporations that are “associated”. The concept of association is defined in the Income Tax Act (the Act) and is explained in more detail later. The business limit is reduced on a straight-line basis for a CCPC and its associated corporations where the group has between $10 million and $50 million of total taxable capital employed in Canada. The concept of taxable capital employed in Canada is beyond the scope of this article, but is generally the total of its shareholder’s equity, surpluses, reserves, and loans and advances to the corporation, less certain types of investments in other corporations.

As a result of the lower corporate tax rates for ABI, incorporated business owners may have more after-tax money to invest inside their corporation. Due to the larger amount of starting capital to invest, a business owner may accumulate more after-tax funds in the corporation than what an individual investor could achieve in their personal investment account. The longer the funds are left in the corporation, the higher the value of this tax deferral advantage.

In 2018, the government introduced rules restricting access to the SBD for CCPCs that have significant income from passive investments with a goal to reduce or eliminate this tax deferral advantage. Under these rules, the business limit is reduced, on a straight-line basis where a CCPC and its associated corporations have between $50,000 and $150,000 of passive investment income in a year.

Specifically, the business limit is decreased by $5 for every $1 of passive investment income above the $50,000 threshold. The business limit is eliminated if a CCPC, and its associated corporations, earn at least $150,000 of passive investment income in a year. The rules reducing the business limit operate alongside the rules that restrict the business limit where the amount of taxable capital employed in Canada exceeds $10 million. To summarize, the reduction in a corporation’s business limit is the greater of the reduction based on passive investment income earned in the corporation and its associated corporations, as well as the reduction based on taxable capital employed in Canada.

Calculating passive investment income

For the purposes of calculating the reduction to the business limit, you need to determine the corporation’s “adjusted aggregate investment income” (AAII) which consists of certain types of investment income earned by the corporation. AAII generally includes net taxable capital gains, interest income, portfolio dividends, rental income and income from savings in a life insurance policy that’s not an exempt policy. AAII excludes certain taxable capital gains (or losses) realized from the disposition of active business assets and shares of certain connected CCPCs. Corporations are connected to each other if one corporation controls the other or one owns more than 10% of the fair market value and voting shares of the other corporation. AAII also excludes net capital losses carried over from other tax years and investment income that pertains to and is incidental to an active business (e.g., interest on short-term deposits held for operational purposes, such as payroll or to purchase inventory).

The test for accessing the SBD is an annual test based on AAII earned by a CCPC and any associated corporation in the taxation year that ended in the preceding calendar year. As a simple example, to determine a CCPC’s SBD for its taxation year ended December 31, 2025, the corporation’s AAII for its 2024 taxation year would need to be calculated. In this example, it’s assumed that the CCPC isn’t associated with any other corporations.

Determining a CCPC’s SBD becomes more complex where there are associated corporations, and the corporations have off calendar year ends. Consider a situation where a CCPC has an October 31 year-end, and an associated corporation has a June 30 year-end. In determining the SBD for the CCPC that has a taxation year-end of October 31, 2025, the corporation would need to calculate its AAII for the taxation year ending October 31, 2024, and the AAII for its associated corporation for its taxation year ending June 30, 2024 (even if this associated corporation isn’t a CCPC).

Since this is an annual test, it is possible that a corporation could regain access to the SBD if its passive investment income was high in one tax year but lower in another tax year.

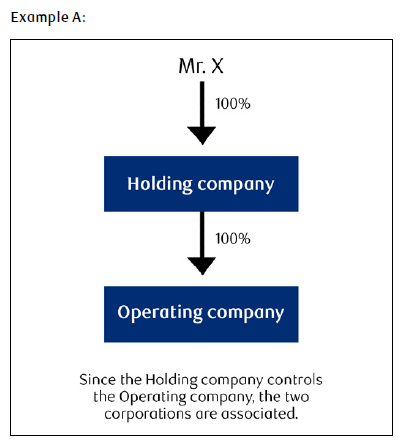

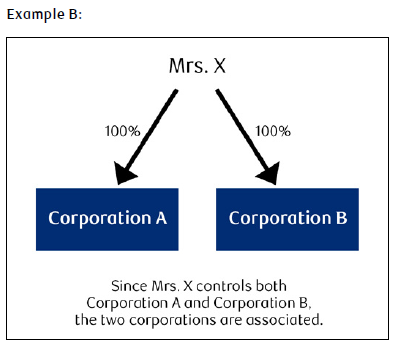

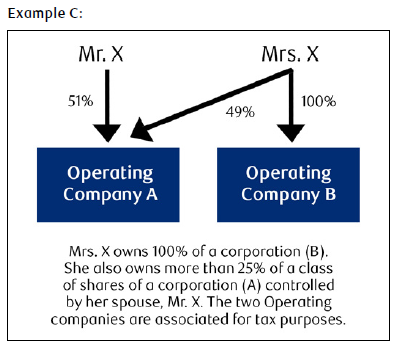

Association rules

As mentioned, the reduction to the business limit for any particular corporation is based on the AAII of the corporation and any associated corporation. The concept of associated corporations is defined in the Act. The test for determining whether corporations are associated relies on the control of the corporations. A detailed discussion of the association rules is beyond the scope of this article, but here are some examples of situations where two corporations may be associated:

Since the corporations in these mentioned examples are associated, AAII earned in one corporation will impact the associated corporation’s ability to access the business limit. As well, since they are associated, they will have to share the business limit.

There are anti-avoidance rules to prevent transactions intended to avoid the reduction to the business limit, such as transferring or lending property to a related but unassociated corporation. If you or your family members own shares of different corporations, speak to a qualified tax advisor to determine whether these corporations are associated.

Implications of rules limiting access to SBD

The passive income business limit reduction rules impact CCPCs that earn ABI, seek to claim the SBD and have AAII over $50,000. Moreover, they only impact CCPCs to the extent that their ABI exceeds the reduced business limit. If the reduced business limit is still greater than the ABI earned by a corporation, the ABI will continue to be taxed at the small business tax rate. For example, a CCPC that has ABI of $100,000 and a reduced business limit of $400,000 will not be affected by these rules. The corporation’s ABI of $100,000 will still be taxed at the small business tax rate. This measure also doesn’t impact a company earning only passive investment income, such as an investment holding company.

As mentioned before, if a CCPCs passive investment income eliminates access to the federal SBD, the ABI will be subject to tax at the general federal corporate tax rate. If ABI is taxed at the general federal corporate rate, as opposed to the federal small business tax rate, it can be paid out to a shareholder as an eligible dividend (as opposed to a non-eligible dividend). An eligible dividend is more preferentially taxed than a non-eligible dividend.

Example: How these SBD rules may impact business owners

Joe is a doctor and the sole shareholder of a medical professional corporation. Joe’s corporation isn’t associated with any other corporations and the taxable capital employed in Canada doesn’t exceed $10 million. The corporation earns $700,000 of ABI annually. Joe has also accumulated a $2 million portfolio of investments in his corporation, which generates a 6% annualized investment return consisting of interest income and portfolio dividends ($120,000 of AAII).

If Joe’s corporation earned less than $50,000 of AAII, the first $500,000 of ABI earned in Joe’s corporation would have been taxed at the federal small business tax rate of 9% resulting in $45,000 of federal taxes payable. However, since Joe’s corporation earned $120,000 of AAII, the corporation’s access to the SBD will be limited. For every dollar of AAII earned in excess of $50,000, the business limit will be reduced by $5. So, the small business limit for Joe’s corporation will be reduced from $500,000 by $350,000 [($120,000 - $50,000) x $5 = $350,000]. This means only $150,000 of ABI will be taxed at the small business rate. The remaining ABI will be taxed at the general federal corporate tax rate of 15%. As a result, Joe’s corporation will pay $21,000 more in federal taxes on the first $500,000 of ABI.

As a result of these SBD rules, Joe will have fewer aftertax dollars to invest in his corporation. However, Joe may still decide to leave the profits of his business inside his corporation to be taxed at the general federal corporate tax rate of 15% versus taking it out as a salary or bonus to be taxed at 33%, assuming Joe is subject to the highest federal personal tax rate. This is still a significant tax deferral, and also assumes that Joe doesn’t need the funds personally now or in the near future.

Provincial differences

As mentioned previously, Ontario and New Brunswick didn’t adopt the federal passive income business limit reduction rules. In these provinces, even if your corporation’s access to the SBD is limited federally because its passive income exceeds the $50,000 threshold, it isn’t limited provincially. The corporation would still have access to the provincial SBD on its first $500,000 of ABI. The impact of the SBD rules in these provinces is therefore not as significant. In addition, as mentioned above, if your corporation’s ABI is taxed at the general federal corporate tax rate as opposed to the federal small business tax rate, the corporation can pay this income out to a shareholder as a preferentially taxed eligible dividend. This means that in these provinces, if the business limit reduction rules apply to your corporation, the net cash retained by a shareholder may be greater than if these rules didn’t apply. You should consult with a qualified tax advisor to determine the impact of these SBD rules for your corporation.

Potential strategies and investment solutions

If you’re the owner of a CCPC, consider how these rules impacts your corporation. If your corporation (together with any associated corporations) has significant passive assets and you’re concerned that the annual passive investment income earned on these assets will exceed $50,000 and impact your corporation’s ability to claim the SBD, speak to a qualified tax advisor about any actions you should take, as well as potential investment and asset allocation strategies going forward.

You may consider reducing assets in your corporation that are generating investment income or removing excess cash in order to alleviate the grind to the SBD. For example, if your corporation has a positive capital dividend account (CDA) balance, you may consider paying out a tax-free dividend to you or other shareholders. Also, if you have made loans to your corporation in the past, you may consider repaying these loans as shareholder loan repayments are tax-free to you.

If your corporation has long-term investments with accrued gains or engages in a buy and hold strategy, it may make sense to dispose of these investments slowly over time to avoid a grind to the business limit. Alternatively, your corporation may want to dispose of all of these securities with unrealized gains in one particular tax year. This may impact your corporation’s ability to access the SBD in the following tax year; however, your corporation may be able to regain access to the SBD in a future tax year, as the $50,000 threshold is an annual test, and your corporation may have less investment income in a future year. As well, consider realizing capital gains and losses in the same tax year. Capital losses can only be used to reduce AAII in the year they are incurred and only if there are adequate capital gains. Net capital losses carried over from other years can’t be used to reduce AAII.

When choosing passive investments, your corporation may want to consider investing in a portfolio of investments that produce deferred capital gains (e.g., non-dividend paying stocks) as opposed to dividends or interest income. Only half of a capital gain is taxable and would be included as part of the $50,000 threshold.

Your corporation may also wish to consider exchange traded funds or mutual funds that don’t make annual distributions or that generate tax-free return of capital (ROC) distributions. Generally, from a tax perspective, it’s better to hold ROC investments personally. However, if your passive investment portfolio is already inside your corporation, receiving non-taxable ROC on your passive investments wouldn’t be included in the corporation’s AAII.

When the investment is eventually sold, this may result in a capital gain, half of which would be included in the calculation of AAII. Please note that ROC distributions can’t be withdrawn from your corporation tax-free.

Another option may be to invest in a permanent life insurance policy if you have an insurance need and will likely never need the funds in your lifetime. Income from a non-exempt life insurance policy is included as part of the $50,000 passive investment income threshold. Income earned in an exempt life insurance policy, however, isn’t included in the calculation of AAII.

In certain circumstances, it may make sense for your corporation to set up a registered pension plan, such as an Individual Pension Plan (IPP). Funds contributed to an IPP are held separate from the corporation’s assets. Income earned in the IPP is tax-deferred until withdrawn and wouldn’t be subject to these measures.

If you have philanthropic intentions, consider whether your corporation should make a donation instead of you personally. Your corporation can claim a deduction for the amount of the donation and reduce the assets in your corporation that may generate passive income. If your corporation makes an in-kind donation of securities with accrued gains, the corporation will not be subject to tax on these accrued gains. These capital gains will also be excluded from the calculation of AAII. As well, your corporation will receive an addition to the capital dividend account for the non-taxable portion of the capital gain (i.e. 100% of the capital gain). This may increase the amount of tax-free dividends that can be paid out of the corporation.

All of these potential strategies have benefits and costs, which must be analyzed before implementing. Speak to a qualified tax advisor to determine if any of these strategies or investment solutions makes sense for you.

Conclusion

In light of these rules, if your corporation earns ABI, you may want to review your corporation’s investment portfolio with your RBC advisor and a qualified tax advisor. If you hold significant passive investments inside your CCPC, your investment strategy may change to one that has the least impact on the reduction to the SBD. This may allow your corporation to continue benefitting from the tax deferral and may result in more funds being available in the corporation for your family and your retirement.