Chapter 41: Good Stocks & Good Companies

Dear Clients,

In our previous December installment, we discussed our investment philosophy of uncovering “good stocks that are also good companies.” In the current investment paradigm, these investments are leading a breadth of structural productivity enhancements in their end markets, as they represent the few earnings compounders that have both the financial capacity and proprietary data to productize generative artificial intelligence (AI). The data/infrastructure required to monetize AI continues to be a secular growth opportunity, with holdings such as NVIDIA, Microsoft, and ASML as examples of innovation-led growth. Please see our June 2023 investment journal for a detailed deep dive into NVIDIA (link: Semiconductors as Secular Growth: Nvidia). These holdings are also strong earnings compounders – in other words “good stocks that are also good companies” – as they demonstrate the power of compounding growth over a long timeframe. For example, $5,000 USD of Microsoft shares purchased at inception on March 13th, 1986 would be worth well over $22 million USD today.

In this edition, we wish to address the converse of our philosophy, which is “good stocks that are poor long-term company investments.” Returning to our investment criteria of longevity, sustainability, and profitability, we cite examples of companies which do not match these investment criteria. Examples would include the cannabis industry, regional bank financials, and legacy technology companies. While these companies’ stocks may have exhibited positive price return characteristics intermittently throughout 2023, their longevity tends to be more shortlived without the underlying secular earnings power to support their valuations. As a result, the shares’ ownership base tends to attract a different type of investor – one who is more focused on price performance characteristics over long-term underlying fundamentals. In addition, with the example of regional bank financials, some have become overleveraged as they have tried to grow their asset bases via acquisition, which also amplifies commercial real estate risk, resulting in elevated provisions for loan losses. The result, as we have explained in our prior journals, is that “cheap stocks can come with their own set of reasons,” the primary one being that their earnings and asset quality can be disrupted, leading to asset impairments, which we would define as RISK.

The dispersion of winners and losers within sectors – termed “bifurcation” – is evident in a significant number of the sectors we hold, from large cap financials versus regional banks, to luxury goods versus mass market consumer discretionary, to large cap semiconductors versus emerging small cap technology. Take NVIDIA versus Intel, both in the semiconductor industry, for instance. NVIDIA has fortified its client base with a culture of innovation, in the process creating dominant franchises in new end markets and a vibrant ecosystem. In their case, winner-take-all effects abound, with structural fundamental growth in the data center leading to sustained and long-lived earnings growth. Intel’s product portfolio, on the other hand, is mostly dominated by the PC end market, which is prone to commodification, creating low customer switching costs and low barriers to entry. The results are reflected in each company’s share price: NVIDIA’s YTD return has been +79%, while Intel’s has been minus -10%, even though both companies are in the same sector.

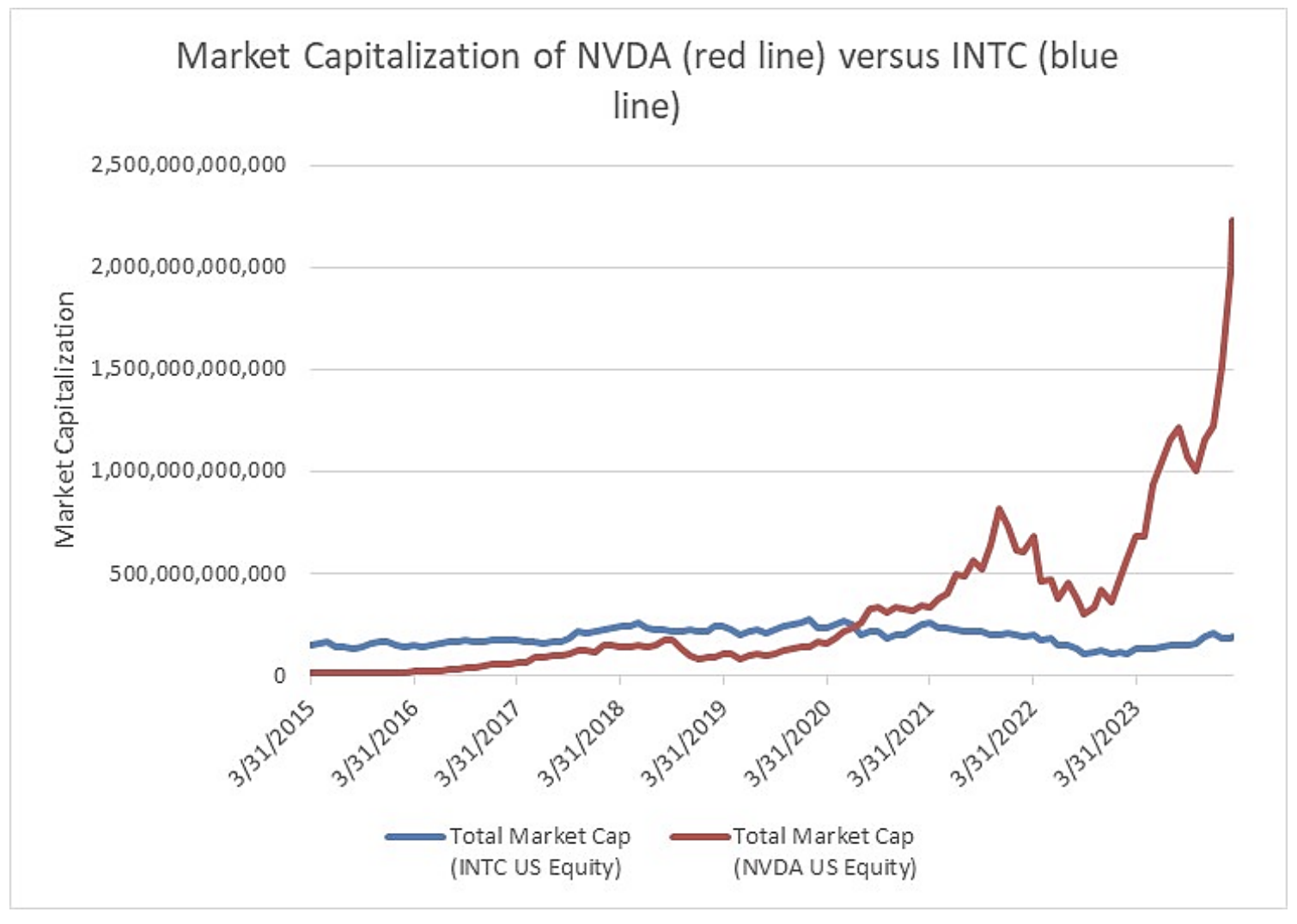

Moreover, over long timeframes, inflection and innovation-led growth eventually prevails. Clients will witness below the market capitalization differences between Intel and NVIDIA over time – as shown in the graph below, it was not too long ago that Intel’s market cap was higher than NVIDIA’s, until NVIDIA’s platform-led growth finally outpaced Intel. Intel, as the purveyor of Moore’s Law in the 1960s and as one of the first investors in advanced lithography, eventually ceded share to its peers, but this took time:

Growth stalwarts have the financial resources to fund investments back into the business, whereas Intel is dependent on government funding to start up its US-based foundries. We have mentioned in the past that in the tech sector, some of these companies create disinflationary tailwinds, which leads to higher anticipated earnings, which in turn leads to upwardly biased leadership within their own sectors. NVIDIA is a case in point.

As clients can see, both company and industry selection have their role to play in developing a wealth-creating investment process. Identifying the paradigm shift of AI productization and the associated secular infrastructure buildout is one step, but the other step is to separate the legacy companies of yesterday from the winner-take-all effects of tomorrow. Identifying companies that have large addressable markets, the ability to expand within them, and grow dominant franchises is one of the cornerstones of our investment process – in other words, identifying, evaluating and selecting “good stocks that are also good companies.” In bifurcated markets especially, we will re-emphasize to clients that selectivity within broad sector and market themes is a distinguishing feature of our investment process.

We hope clients have found this installment helpful. Wishing you and your loved ones a sunny start to spring.

Warmest regards,

Grace Wang, CIM, PFP | Senior Portfolio Manager

Samuel Jang, CFA | Investment Associate | samuel.jang@rbc.com

Leslie Mah | Associate Advisor | leslie.mah@rbc.com | 604-257-7059

Katherine Jialing Yang | Associate | jialing.yang@rbc.com | 604-257-2537

Hazel Chen | Administrative Assistant | hazel.chen@rbc.com | 604-257-2483