“The use of quantity of money as a target has not been a success. I’m not sure I would push it as hard as I once did.”

Milton Friedman, Financial Times – 2003

As this cycle continues to develop, and the true effects of the global lockdowns come into full reality, there will be more and more of an awakening that governments and their citizens will have to deal with the massive amounts of debt and stimulus that were deployed during the past 5-6 months as “stop-gap” measures.

Economics may not be the most “sexy” subject of the possible academic studies, but it sure has an impact on each and every one of us. Each and every day. It’s quite simple actually, the biggest drivers being “supply” and “demand”. That simple formula drives the cost of everything: the food we eat, the cars we drive, worker salaries, athlete’s contracts, movie productions, and yes, stock prices…each and every day….

For anyone who has studied economics, Say’s law was first credited to the French businessman and economist, Jean-Baptiste Say, who wrote in the early-1800s, that:

“It is worth-while to remark, that a product is no sooner created, than it, from that instant, affords a market for other products to the full extent of its own value. When the producer has put the finishing hand to his product, he is most anxious to sell it immediately, lest its value should diminish in his hands. Nor is he less anxious to dispose of the money he may get for it; for the value of money is also perishable. But the only way of getting rid of money is in the purchase of some product or other. Thus, the mere circumstance of the creation of one product immediately opens a vent for other products.”

Say's Law of Markets comes from his book, "Of the Demand or Market for Products", written in 1803:

"As each of us can only purchase the productions of others with his own productions – as the value we can buy is equal to the value we can produce, the more men can produce, the more they will purchase."

Say lived in 1767-1832, that is quite some time ago.

Say was influential because his theories address how a society creates wealth and the nature of economic activity. To have the means to buy, a buyer must first have sold something, Say reasoned. So, the source of demand is prior to the production and sale of goods for money, not money itself.

Say’s law states that the production of goods creates its own demand. This view suggests that the key to economic growth is not increasing demand, but increasing production. Say’s views were expanded on by classical economists, such as James Mill and David Ricardo. But how does supply create its own demand?

If a businessman produces a good, then he will be keen to sell it to realize the profit from the effort put into producing that item. This production creates wages for workers and income for the businessman. Therefore, the production has increased wealth and leads to demand for other goods from a broader range. A multiplier effect of sorts. That’s the reason why Henry Ford paid his workers more than most others did at the time. Simply so they could afford to buy the cars he was producing!

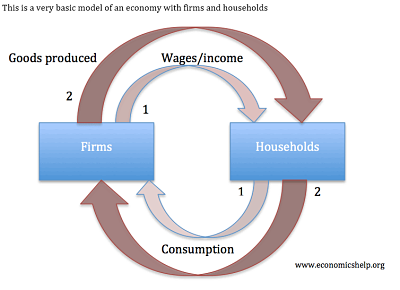

Say argued against claims that businesses suffer because people do not have enough money. He argued that the power to purchase can only be increased through more production. Here’s what it looks like in a very simplified flow chart:

If firms produce $1 million worth of goods. They will be paying $1 million of wages to households. In turn, the households can buy $1 million worth of goods produced by the firms. If the firms now double production to $2 million worth of goods. They will also be paying $2 million of wages to households. In turn, the households can now use their increased wages to buy the increased production of goods.

Say argued it was irrational to hoard money because ‘he is most anxious to sell it immediately, lest its value should diminish in his hands…… i.e. inflation may reduce the value of cash. Remember that folks. I think it will come into play in the near future.

This theory assumes that markets clear and that businessmen produce goods that are demanded by the market.

The circumstances in society at the time behind Say’s applied knowledge are also worth recalling. He not only lived through the French revolution and the Napoleonic wars, but he also experienced not one, but two hyperinflationary money collapses, first “assignats”, and then “mandats”. France had also suffered the collapse of John Law’s paper money in 1720. Therefore, Say was very much aware that money can be highly perishable, and he will have observed that people used it only as the temporary bridge between their production and their consumption. Hence the context in this quote about getting rid of money.

It is interesting to add that Say’s law does not require conditions of a gold standard or sound money, as some may deduce. The condition behind Say’s Law is that it is a fundamental tenet of all humanity that their economies are characterized by the division of labour. The market is a loose term for exchanges of goods and services generally, which is why Say’s law is sometimes referred to as the “Law of the Markets”, but it should be noted that those simple economic tents apply even in a command economy that suppresses personal freedoms. Think the old USSR, Cuba, Zimbabwe, and Venezuela more recently.

Say's Law of Markets is economic theory from classical economics arguing that the ability to purchase something depends on the ability to produce and thereby generate income. Say reasoned that to have the means to buy, a buyer must first have produced something to sell. It states that in a market economy, goods and services are produced for exchange with other goods and services—"employment multipliers" therefore arise from production and not exchange alone—and that in the process a sufficient level of real income is created to purchase the economy's entire output.

The crude formulation of “Say’s Law” is that “supply creates its own demand” which is rather cryptic in meaning. It was famously rejected by John Maynard Keynes in his General Theory (1936). It has been largely ignored by mainstream economists ever since. If left to itself, it was argued that free markets have so powerful a tendency to produce a balance in supply and demand that it will always be very exactly preserved.

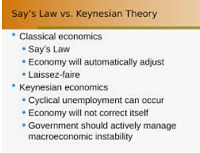

Here is a basic comparison of the two schools of thought:

(Source: Slideshare.net)

Of course, for monetarists like Keynes to acknowledge the early ‘20s and early ‘30s, post-WWII, along with 1979-82 when their superstition was actually cruelly foisted on the economy, they’d have to admit that money supply doesn’t drive economic growth as much as it’s a byproduct of economic growth. Per economist John Stuart Mill, economic activity constitutes money demand, so when useful activity picks up so does money demand increase; rising money in circulation the result.

The above of course explains the contradiction at the heart of the monetarist religion. Deep rooted in the misguided belief that the monetary printing press is the source of future Microsoft’s, Intel’s and Google’s, the monetarist ideology can be its own worst enemy. Like a blindfolded child swinging wildly for the piñata, monetarism is the far more dangerous adult equivalent whereby money supply is blindly targeted without regard to demand for same, nor how the results can be measured. The result is floating free money values that robs money of the very quality that makes it attractive to market players, thus driving down money in circulation.

One truism about the nature of money supply is disputed by monetarist fundamentalists to this day. They, along with their close Keynesian ally in former Fed Chair Bernanke, still believe that the Great Depression was caused by a gold standard-adhering Fed forcing a collapse in the supply of money. What’s funny about the latter is how totally divorced from historical reality it actually is.

So to summarize the implications of Say’s Law:

- The economy should always be close to full employment. There shouldn’t be demand deficient unemployment.

- Economic downturns are not due to a “glut” of supply.

- According to classical economists, any unemployment must be due to wages being artificially kept above the equilibrium level or structural factors, such as lack of skills in specific industries.

- To increase output, we should concentrate on increasing production rather than demand.

- Automatic resource adjustment and utilization in an expanding capitalist economy.

- Money has only a passive role.

- The Rate of interest is a strategic variable.

Criticisms of Say’s Law:

- The mass unemployment and prolonged recession of the 1930s suggested that production does not equal demand. In a recession, there can be insufficient aggregate demand for goods produced.

- Prices and wages are not flexible. e.g. workers may resist nominal wage cuts

- Excess savings. There are examples where there is an increase in savings, and businessman and consumers hoard cash.

- In a liquidity trap, the demand to hold cash is greater than the demand to spend. Banks increase their reserves and the saving rate increases, this leads to a fall in aggregate demand.

- Confidence. In certain circumstances, people may not have the confidence to spend and invest. They may become risk averse and hoard cash in unproductive savings.

- It may be very rational to ‘hoard’ money – especially in a period of deflation or anxiety.

The balance sheet Great Recession of 2008-09, illustrated an example of where banks, consumers and firms were keen to pay off their debts and not spend all their income. This led to a prolonged recession and the economic bounce took longer than in “normal” cycles.

In terms of resemblance to other economic schools, Monetarism is most like Keynesianism in that both elevate demand to the top of the economic pyramid. Keynesians promote economy-sapping government spending and interest rate manipulation to boost demand, while Monetarists advocate economy-suffocating currency devaluation as the path to consumption. Both dismiss Say's Law, the quick dismissal a strong clue that helps explain why the continued use of these close policy cousins has always coincided with slow growth.

In every transaction, there is a buyer and seller. Therefore, an economy must be comprised equally of buyers and sellers. Money is a commodity that facilitates their transactions, and it allows them to sell their goods, services and labour to buy other things. The quantity of money is irrelevant to this law, because it is a functional good just like anything else that’s bought and sold. Yep, it’s a commodity like anything else.

There is a fundamental difference between “goosing” the economy by stimulating demand, which was Keynes’s approach, and stimulating supply. Stimulating demand by monetary inflation may have a temporary beneficial effect, which is reversed over the credit cycle. Monetary inflation however is targeted at getting consumers to spend more amounts to fooling all of the people, which as the adage goes, you can’t do all of the time.

Attempts to do so end up setting off a credit-induced business cycle, where boom is followed by bust. The boom is the people being fooled, and the bust the realization they have been taken for suckers. While governments can play these games and demonstrate that at one part of the credit cycle they have stimulated consumption and that therefore Say’s law appears invalid, taken over the whole cycle Say’s law turns out to be valid after all.

Under that scenario, it looks like this:

- We produce goods and services we may consume ourselves, and the surplus we will sell to others, to enable us to acquire the things we do not produce.

- We need not consume any of our own production, but can sell it all to others, so that we may acquire the goods and services we need or desire.

- Consumption includes deferred consumption, and the portion that is deferred is irrelevant to the law, because the proceeds of production are spent by someone else.

- Money does not need to be involved, and the law covers barter as well.

- Anyone who acquires goods and services from others, without producing something to pay for it, must acquire the wherewithal from someone else, who has produced goods and services in excess of his own consumption.

However…. Say’s law applies to all the economic participants, including the state.

People are paid to create goods and/or services, and can then spend that money on other goods/services. And there’s no point in holding onto money for long periods without spending it because then its value is likely to decrease with inflation. So anytime goods are manufactured or services are rendered, people are paid money, which leads to greater demand. Thus, aggregate production level leads to equal aggregate demand.

Economic discussions would probably be better understood when no one received “free” money. The first rule of economics I learned very early on is: “There is no such thing as a free lunch”. Money on its own, doesn’t feed, shelter, clothe…or more importantly: create jobs. It’s only useful when accepted by producers of the actual good and services. Lockdowns, by their very name, limit economic activity, including anything related to work. Productivity naturally declines…both supply and demand were hit at the same time during this recent crisis.

The “safety nets” that were quickly put into place by enlightened governments to protect against lost wages of the economically displaced, overlook the biggest major factoid: That public and private corporations are not charities. They pay into the aggregate pot that allows all those very distributions to take place. Eventually, if less is going INTO the pot, and MORE is flowing out in social support…eventually the pot is going to run out of funds to prop up all of the alarmism and “free money”. It was British PM Margaret Thatcher who famously said that “The problem with socialism is that you eventually run out of other people's money.”

Money itself is not “wealth”. Money merely moves that wealth around. Governments can’t continue to pay idle workers perpetually simply because an ability to not work is itself a consequence of production. The truth is governments can only subsidize a lack of work as long as others are working in a prodigious fashion to refill that pot. Governments really don’t produce anything, they simply help themselves to actual production in the economy, and redistribute it. Period. Without the efforts of private production in the economy, governments have absolutely zero to hand out.

So what seems to be happening right now in our global economy is the basic truth of Says Law, which indicates it is a real and applicable theory. Consumption can only happen AFTER production. Makes sense simply by definition. Wouldn’t everyone simply love to be free to consume anything and everything without the effort that enables it? Of course, if we all inherited the millions to be able to do it. And ironically, if one thinks about it, those heirs are freely able to consume at will simply because those who came before them had the ability to produce with abandon to create that wealth. Consumption is a consequence of, not a driver, of economic growth. Consumption is the reward after the production. Right now, we have it backwards.

No nation in history ever consumed its way to prosperity…ever.

Stay tuned,

Vito Finucci, B.COMM, CIM, FCSI

Vice President and Director, Portfolio Manager

Learn More

This information is not investment advice and should be used only in conjunction with a discussion with your RBC Dominion Securities Inc. Investment Advisor. This will ensure that your own circumstances have been considered properly and that action is taken on the latest available information. The information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable at the time obtained but neither RBC Dominion Securities Inc. nor its employees, agents, or information suppliers can guarantee its accuracy or completeness. This report is not and under no circumstances is to be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy any securities. This report is furnished on the basis and understanding that neither RBC Dominion Securities Inc. nor its employees, agents, or information suppliers is to be under any responsibility or liability whatsoever in respect thereof. The inventories of RBC Dominion Securities Inc. may from time to time include securities mentioned herein. RBC Dominion Securities Inc.* and Royal Bank of Canada are separate corporate entities which are affiliated. *Member-Canadian Investor Protection Fund. RBC Dominion Securities Inc. is a member company of RBC Wealth Management, a business segment of Royal Bank of Canada. ®Registered trademarks of Royal Bank of Canada. Used under license. © 2020 RBC Dominion Securities Inc. All rights reserved.