2020 easily set a record for corporate debt issuance with $2.28 trillion of bonds and loans, comprising both new bonds and bonds issued to refinance existing debt. And through September of this year companies have already brought an additional $1.56 trillion to market. Add it all up and the nonfinancial corporate debt and loan market now stands at approximately $11 trillion, according to Federal Reserve data.

But debt levels can’t simply be looked at in isolation, it’s all relative. Corporate debt levels haven’t strayed too far from long-term trends relative to the gross domestic product (GDP) of the economy, just one way of gauging the relative size of the corporate bond market. The spike in the corporate debt-to-GDP ratio caused by the pandemic was largely due to the drop in GDP. Now that GDP has recovered to pre-pandemic levels, and is still projected to grow at well above the two percent long-term trend through at least 2023 based on Bloomberg consensus forecasts for October, the ratio is likely to decline further below 50 percent.

With the economic recovery progressing, growth in corporate debt levels is back near its long-term trend

Source - RBC Wealth Management, Bloomberg; data through Q2 2021, based on $11.2 trillion nonfinancial corporate debt and nominal GDP of $22.7 trillion

It is little wonder that companies are binging on debt as the average coupon paid by companies, according to the Bloomberg Barclays US Corporate Bond Index, is now at a fresh record low of just 3.6 percent, compared to more than four percent prior to the pandemic. The story is the same for the speculative-grade corporate bond market where the lowest-rated companies are paying an average interest rate of only 5.7 percent, down from nearly 6.5 percent prior to the pandemic, and also the lowest on record.

While fears abound that there are systemic risks due to elevated debt levels across the globe, the metrics cited above suggest to us that systemic risks from a growing U.S. corporate bond market remain low.

So debt is up, but liquidity is improved with record cash on balance sheets, and interest costs are down—might companies actually emerge from the pandemic in far better financial positions despite rising debt loads?

The upside of down

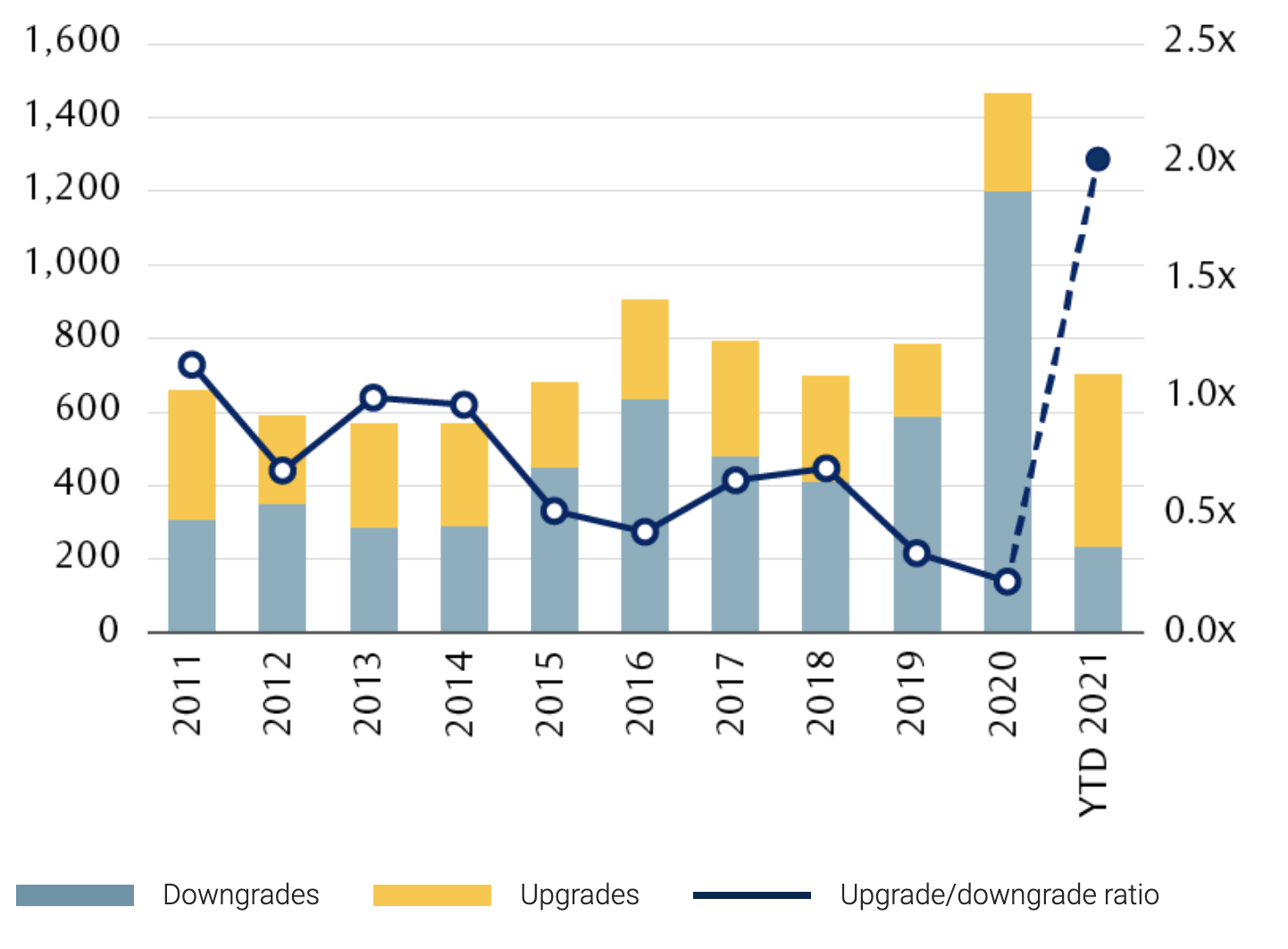

It would likely come as little surprise that 2020 saw extensive negative rating actions taken by the major credit rating firms, with S&P Global Ratings downgrading the credit profiles of approximately 1,200 U.S. firms alone. But in 2021 upgrades have been the name of the game, with upgrades outpacing downgrades by a factor of nearly two-to-one.

And market-based assessments of risks across the corporate bond landscape support these trends. Since October 2020, the Bloomberg US High Yield Fallen Angels Index—or companies that saw their credit ratings downgraded from investment grade to speculative grade—has delivered total returns of over 15 percent, compared to just 10 percent for the broad speculative-grade index, and only two percent for investment-grade corporate bonds.

After a number of credit rating downgrades in 2020, credit upgrades reached a decade-high level in 2021

Source - RBC Wealth Management, Bloomberg; shows credit rating changes by S&P Global Ratings, excludes credit watch changes; data through 10/27/21

Pay thanks to the Fed?

Of course, the defining feature of the pandemic was the Fed’s first foray into credit markets, taking the unprecedented step of directly lending to companies and purchasing individual corporate bonds and corporate bond-related exchange-traded funds (ETFs) on the secondary market.

Though the Fed’s facilities were large in potential size, the actual support provided was ultimately quite minimal, with total holdings only approaching about $15 billion, or barely 0.10 percent of the total market. In fact, as of August 2021 the Fed’s portfolio of corporate bonds and related ETFs has either matured or been sold, with the Fed no longer holding any positions in corporate bonds.

The Fed’s much-needed backstop likely helped to stem some of the worst possible outcomes of the 2020 recession, where the default rate peaked at roughly 7.5 percent, only half of the market-weighted rate of defaults seen during the recessions of 2001 and 2008. The greater factor was perhaps the brevity of the downturn, at barely two months due to a strong policy response that supported a lower default environment.

But what might this all mean for the future of Fed policy as it relates to corporate bond markets? Could a perceived backstop from the Fed forever change credit markets and how they function, especially in economic downturns?

In our view, the Fed’s actions were unprecedented because the pandemic was unprecedented, given the effective shutdown of a globally intertwined financial system. We don’t expect the steps taken to feature regularly in the Fed’s toolkit in more run-of-the-mill recessions, though risk premiums demanded by investors in U.S. credit markets may decline modestly over the long term now that the Fed has broken the glass on such a measure.

You get what you pay for

So corporate balance sheets are clearly on the mend, and systemic risks emanating from the U.S. corporate bond market appear to be low. How then should bond investors be thinking about portfolio positioning and opportunities in the aftermath of what has been an extraordinary two years for markets?

For investors, the economic recovery and improvement in the credit backdrop has already been nearly fully priced into the market. Credit spreads—or the yield offered by corporate bonds over comparable Treasury yields for associated credit risk—remain near historical lows. The Bloomberg index of investment-grade corporate bonds now yields just 0.85 percent over Treasuries, well below the decade average of 1.3 percent. Speculative-grade corporate bonds offer investors 2.9 percent over Treasuries, but that is also lower than an average yield advantage of 4.5 percent during the past 10 years.

While we think investors should have portfolio exposure to both sectors as part of a well-diversified bond portfolio—the risk exposures between the two are actually quite different.

Investment-grade corporate bond yields usually move closely in line with movements in Treasury yields—if Treasury yields rise, as is broadly expected over the next couple of years based on Bloomberg consensus forecasts, investment-grade bond prices could fall modestly as bond yields and prices move inversely.

But speculative-grade bonds have less sensitivity to Treasury yields, and can actually perform quite well in a rising rate environment. If Treasury yields are moving higher because of a better economic growth backdrop, then earnings for speculative-grade companies will likely improve, and credit spreads will likely fall—offsetting higher Treasury yields.

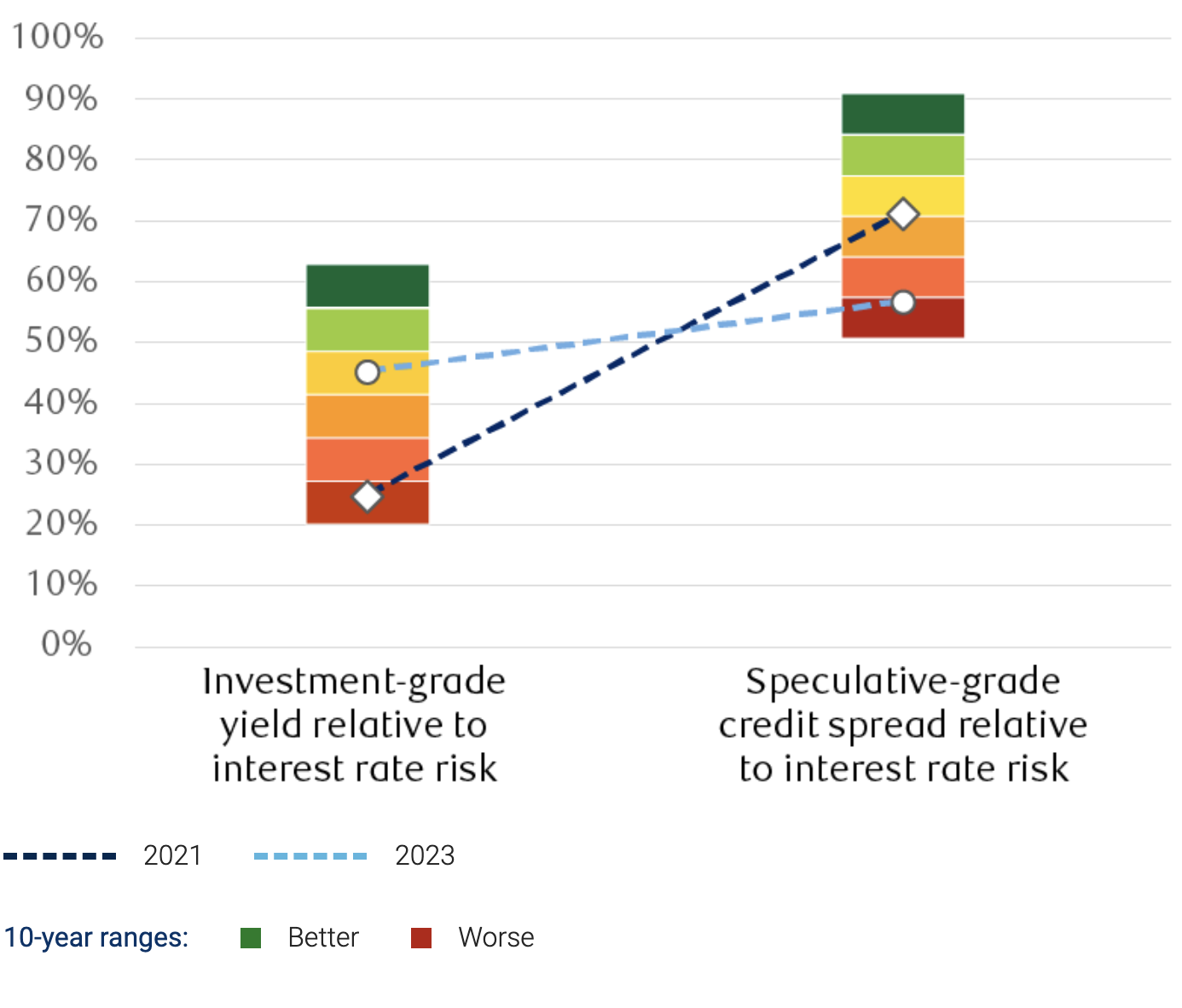

These dynamics and how we assess relative value within each sector according to key risk metrics are shown in the chart and tables below.

- Investment-grade corporate bonds: If the key risk for investment-grade bonds is interest rate risk, then investors should expect to be compensated for that risk. But at the moment, the sector yields only 2.2 percent, while the duration—a measure of interest rate sensitivity—is at an all-time high of 8.7 years. That ratio of yield per unit of interest rate risk is just 25 percent, a historically low level of yield compensation for interest rate risk that isn’t currently attractive for investors, in our view.

- Speculative-grade corporate bonds: If the key risk for speculative-grade bonds is underlying credit risk, then investors should expect to be compensated for that risk. The sector offers a three percent yield over Treasuries for credit risk at present, for an all-in yield of 4.2 percent. This means that over 70 percent of the total yield is coming in the form of credit risk compensation, which is about equal to the average that investors have earned over the past decade.

The pendulum may swing from favoring credit risk to favoring interest rate risk in the years ahead

| Investment-grade yield relative to interest rate risk | Speculative-grade credit spread relative to interest rate risk | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield | Duration | Ratio | Spread | Yield | Ratio | |

| 2021 | 2.2% | 8.7 yrs | 25% | 3.0% | 4.2% | 71% |

| 2023 | 3.4% | 7.5 yrs | 45% | 2.5% | 4.4% | 57% |

Source - RBC Wealth Management, Bloomberg consensus yield forecasts for October 2021

This relationship between the two sectors should shift back in favor of investment-grade corporate bonds as yields rise through 2023 based on current consensus forecasts.

The main point being, we would maintain a modest Overweight recommendation to speculative-grade corporate bonds at the early and middle stages of an economic recovery, but would begin to reduce that exposure as the business cycle matures. Current corporate default forecasts over the next 12 months are below two percent and the sector can be an attractive place to augment portfolio income in what is still a low-yield environment.

Speculative-grade bonds may not be suitable for all investors. But over the near term we see few credit risks on the horizon for U.S. corporate bond markets, and little risk that the increased debt levels following the global pandemic will act as the potential source of the next crisis.