...that financial markets would become choppier through the second-half of the year as this change of pace was digested.

Fast-forward to today and the first part is certainly true. US GDP figures released last week showed that growth in Q2 was a full 2% below expectations, which would be a heart-stopping amount in any normal year. Other recent indicators like the Purchasing Managers Index and Total Home Sales (see charts below) have also shown a sharp down-tick thus far this summer.

Flash output PMI, developed markets (left); Total US home sales (000’s, right)

Source: J.P. Morgan, IHS/Markit (left); RBCCM, Haver Analytics (right)

Interestingly, the deceleration looks set to continue. This is due in part to the impending withdrawal direct government support programs. For example, in the US, the moratorium on tenant evictions ended this past weekend. More broadly, unemployment insurance supplements in the US – which have been rolling off in some states since June – will come to an end for every state in about 30 days, and the federal government has made it clear they will not be extended (note that subsidies here in Canada have by contrast been extended, which is perhaps no surprise given high anticipation of a coming federal election).

On top of these factors is the much more obvious threat to economic growth: a rapid rise in new COVID cases from the delta variant. On one hand, it seems likely that governments of countries with high vaccination rates will opt not return to aggressive restrictions, given the apparent effectiveness of vaccines in reducing the worst outcomes and the obvious economic damage of lockdowns. On the other hand, it seems equally likely that consumers – on average – will more actively self-police the situation this time by slow playing a full return to normal life, even if just for a couple more months. Does one need to fly to overseas right now and share air with 300 people for 10+ hours, or might they wait for another eight weeks before booking that trip? Self-policing by corporations is already evident, with Apple and Google amongst others both pushing off their return-to-office plans last week.

Of course, arguably the biggest economic wild card of the moment is whether the resurgence in infections leads to yet another variant. That certainly sounds like a frightening thought at first blush; but then again, new variants are not bad by definition, they are simply different. Sometimes different can be harmful in terms of transmission and severity, and sometimes it can be helpful.

Given all of these variables, the fact that there has been no meaningful stock market pullback this year and that equities are hovering near all-time highs seems, at first glance, to range somewhere on the rationality spectrum between naïve and delusional. But it is important to keep in mind that while the items above are uncertainties, they are known ones.

Prices in financial markets are based on predictions about the future. The pesky part about the future, of course, is that its unknowable. So as investors, we make educated guesses about potential outcomes and allocate our money accordingly; which is to say that market prices reflect a probabilistic approach by investors. As discussed in many of our previous updates over the years, when the main uncertainties facing the economy are fairly clear – when they are known unknowns – financial markets tend to do a pretty good job of handicapping the probability of outcomes in prices.

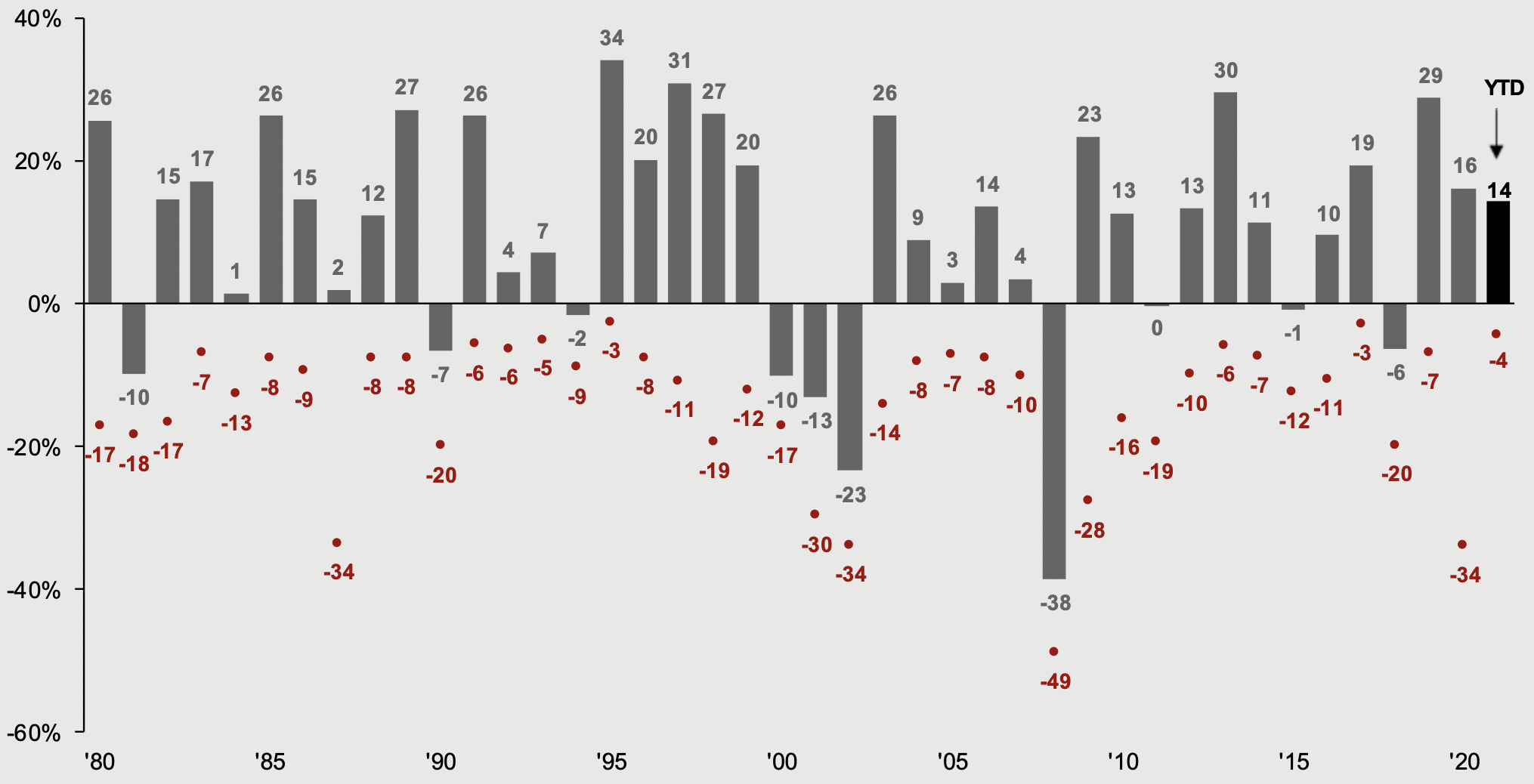

To make that a bit more quantitative, take look at the graph below. It maps the price return of the S&P 500 for each year since 1980 (grey bars), together with the largest market sell-off experienced in each of those same years (red dots). If you count up the dots, you’ll discover that in exactly half of the past 40 years, the worst stock market decline was only a single digit number. Meaningful market corrections are uncommon outside of recessions.

S&P 500 annual returns & intra-year declines: 1980 – Jun 2021

Source: J.P. Morgan Asset Management, FactSet, S&P

Source: J.P. Morgan Asset Management, FactSet, S&P

If there is one thing we are not in right now, it is a recession. GDP growth may be decelerating, but it is still very strongly positive. Consumers are more financially healthy than they have been in a generation (more true in the US than in Canada), global monetary policy remains very supportive through low interest rates, the global banking system is exceptionally well capitalized, etc.

Importantly for equity markets, this strength is manifesting itself in corporate earnings – about two-thirds of S&P 500 companies have now reported Q2 earnings, of which a record-breaking 90% have beaten analyst estimates. That follows on the heels of Q1, which itself was a record-breaker. These positive earnings surprises so far have been on average almost 20% ahead of expectations, which is easily the biggest overshoot since aggregated earnings data became available. So, the strong rally in equity markets this year hasn’t been due to unfounded optimism; it has been due, at least in part, to real-world results.

Putting that all together then, the continuous grind higher of equity markets in the face of a decelerating economy and some clear uncertainties is perhaps not as naïve as it first seems. Risk is an important and necessary part of investing in order to achieve decent returns, and so long as those risks are in plain sight, markets tend to do a good job at discounting them. With this as context, we certainly have not been surprised to see the previously discussed “Dash to Trash” within the stock market mean-revert over the past few months. We also still expect to see some choppiness through the balance of the year, but with any sell-off presenting more of an opportunity than a cause for concern, with downside likely limited to the standard, non-recession single digit range shown above.