2019 was an unusually quiet and stable year for the Canadian dollar. 2020 has been anything but. Canada’s currency was worth 77 US cents at the start of the year but lost 10% of its value in recent weeks, dropping to a four year low of just 69 cents before recovering slightly in the past few days. Broad strengthening in the US dollar has been a factor—the greenback was at times up more than 9% against all currencies (on a trade-weighted basis) and about 7.5% higher compared with advanced economies. Among the latter, Canada is joined by other commodity producers (Australia, Norway) and countries launching new quantitative easing programs (New Zealand, Australia again) in seeing double-digit declines in their currencies.

That the Canadian dollar has weakened in an environment of significant risk aversion, collapsing energy prices, and general demand for US dollars is unsurprising. Given continued uncertainty over the depth and duration of coronavirus containment measures, it’s too early to say whether risk appetite or oil prices have hit bottom. New easing announced by the Bank of Canada—it cut the overnight rate to its effective lower bound and launched its first QE program on March 27—could also send the currency lower as markets continue to digest those moves. But we don’t think the Canadian dollar is headed for its all-time low of 62 US cents seen in the early-2000s.

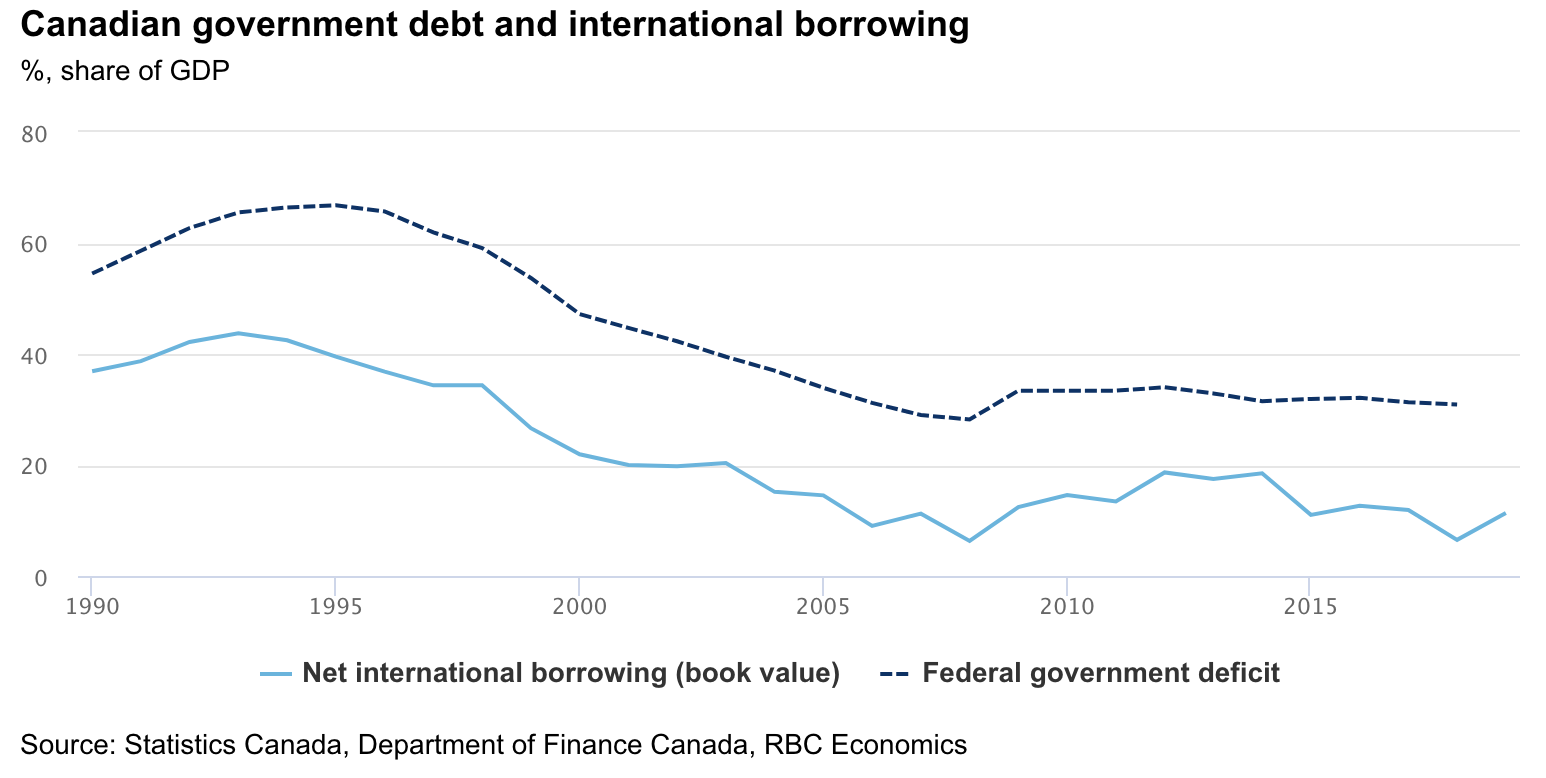

We’ve come a long way from the “Northern Peso” days of the mid-1990s when Canada lost its AAA credit rating and federal government debt was more than 60% of GDP. Having run surpluses for a decade prior to the financial crisis, Canada’s federal debt-to-GDP ratio now stands at a G7-low 31%. A significant increase in government spending to deal with the current crisis (along with a sharp drop in revenues amid slower economic activity) could push that ratio 10 percentage points higher, but would still leave Canada the envy of other countries that are launching deficit-financed stimulus of their own. An improved fiscal position has helped Canada rein in its net international borrowing (the country is even in a net asset position on a market value basis). With lower oil prices cutting into Canada’s $90 billion oil exports, a larger current account deficit will hurt that net asset position. But the country is still a long way from the international debt levels seen in the 1990s.

The Canadian dollar’s darkest days have come amid periods of financial market volatility, from the 1998 Russian financial crisis and LTCM collapse to the dot-com bust in the early-2000s. The same dynamic is at play now as investors grapple with an unprecedented, sharp downturn in global economic activity. The Canadian dollar’s stronger relationship with oil prices (compared with decades ago) isn’t helping. But a healthier fiscal position and less reliance on external borrowing should provide a backstop. 69 cents might not be as bad as it gets, but we doubt 62 cents will come into view.

Josh Nye is a senior economist at RBC. His focus is on macroeconomic outlook and monetary policy in Canada and the United States. His comments on economic data and policy developments provide valuable insights to clients and colleagues, and are often featured in the media.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.